Why are board games that simply let Black players have fun still all too rare?

Examining the Leisure Divide.

Presumptions about leisure - how it is imagined and represented, who has it, and who it is for - have long contributed to the generation of race and class identities in the United States. Images of white families engaged in various leisure activities contributed to an iconography of whiteness that could (and often does) substitute for a verbal lexicon that might otherwise require the use of explicitly racist language. Board games are part of this much larger material and representational field.

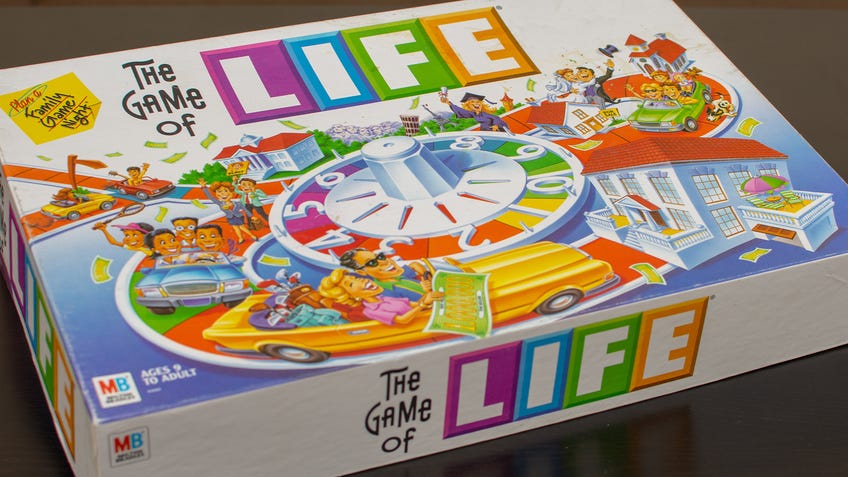

Most games, like nearly every item marketed to US consumers, were designed, manufactured and marketed for a presumed white audience. Even more narrowly, they were designed for white, heterosexual, nuclear families. Ideas about race and gender/sexuality are deeply intertwined in game design just as they are elsewhere throughout culture and society. As the box top for The Game of Life indicates, it is a “family game” intended to promote the kind of heteronormative “family togetherness” that became increasingly promoted after World War II, when America’s economy likewise depended on that particular structure for the accelerated consumption of consumer goods. Leisure - the ability to have free time and to spend it equally freely and as one wishes, and for purely recreational or relaxing purposes - has become symbolic both of whiteness and of middle-class identities.

A 1966 Milton Bradley advertisement describes its top-selling games as “sensational” and “zany”. Could only white consumers envision themselves engaging in leisure activities that connected them to attributes such as “zany” and “sensational”? Imposed white norms of respectability combined with the behavioral codes required of Black families for their safety demanded levels of decorum from the latter that the former need not have concerned themselves with in the past or now.

In the imagination of game designers and manufacturers, for Black families, time away from work, it seems, was time to be used productively.

Nevertheless, some games were designed and marketed specifically for Black Americans. Tellingly, these games were quite different from those designed with a white-by-default audience in mind. Rather than zany or sensational, they were instead primarily serious and didactically focused, aimed at educating Black families and their children about the value of Black culture, or attempting to provide strategies for survival and liberation through family play. The games and their graphics support Black respectability, but within a very narrow range of representational options. In the imagination of game designers and manufacturers, for Black families, time away from work, it seems, was time to be used productively.

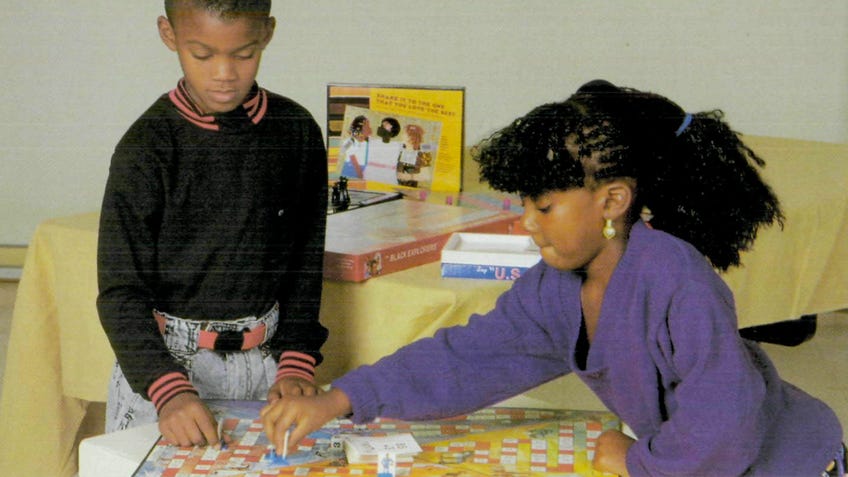

For example, Pursuit: The Black Man Strides towards Equity (1954–1970) is a game that focuses on the history of the civil rights movement. Similarly, The Black Experience: American History Game from 1971 and African-American Discovery, which was subtitled “An Exciting Black History Game,” both endeavoured to instruct and uplift rather than to simply entertain. The box covers for each of these games depict events from Black history through either photographs or drawings. African-American Discovery included an illustration of a Black family playing the game together, the father’s arms encircling his smiling family; the game’s explicit intention was to help families learn and to reinforce knowledge about African Americans and their contribution to American history.

Perhaps most poignant of all is The Black Community Game: What Will You Do When You Get in a Situation? Designed for players ages eight to eighty, the game presents scenarios that teach players how to navigate the social and cultural challenges faced by Black people and illustrates ways the community can interact and cooperate to help its members survive and thrive.

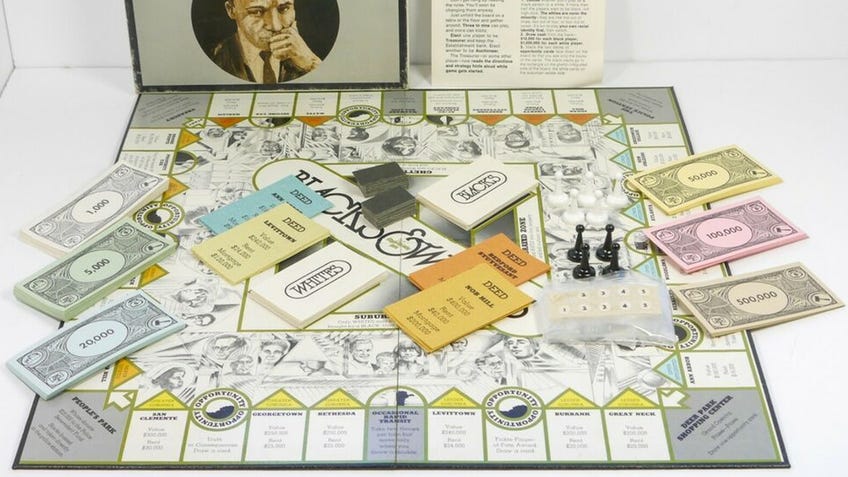

One of the few games to bridge the Black and white experience (with an emphasis on spatial politics) was the 1970 game Blacks & Whites. Produced by Psychology Today magazine and borrowing heavily from Monopoly, the game intended to convey “something of what it’s like to go through life being forced to play with a stacked deck”. White players start with more money; game mechanics steer Black players’ property purchases toward “ghetto” (Sugar Hill, Watts) and racially integrated areas on the board (Berkeley, New Orleans) rather than towards Grosse Pointe, Levittown and other predominantly white communities within the “estate zone” and “suburban zone”. Players draw from a collection of segregated “opportunity cards” with events such as one in which Black militants amend the building code to “force slum property owners to pay a $50,000 fine for each property”.

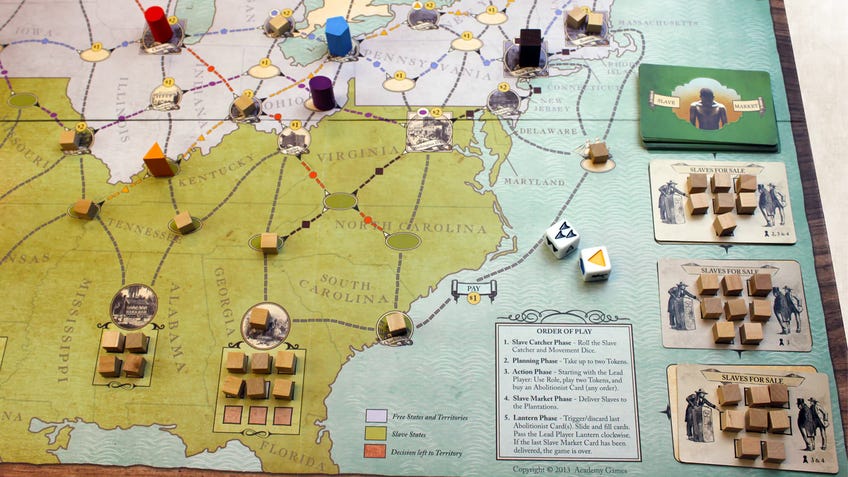

Why are the majority of games for Black families primarily educational or focused on “a celebration of Black identity”? Alternatives surely exist. One can imagine Afro-futurist board games that would move players through visually enticing Black utopias, immersed in exciting adventure routes that emphasise goal achievement and Black joy while also entertaining participants. Instead, board games continued to follow the didactic model with examples like 2012’s Freedom: The Underground Railroad game, in which players join abolitionists in efforts to lead slaves to freedom.

We might ask why the representational field for Black leisure is so limited, and why “zany” fun is imagined as being only for whites.

We also might ask why the representational field for Black leisure is so limited, and why “zany” fun is imagined as being only for whites. What should we make of these different ways of imagining “play” for Black and white audiences? Fundamentally, the games demonstrate what Jessie Whitehead has called “the limited presence of visual narratives of Black Americans,” a problem that sits at the heart of work by artists such as Kerry James Marshall and Betye Saar and has been the subject of inquiry by scholars such as Tricia Rose and Kellie Jones. As Rose has demonstrated, the representational spectrum for depicting Black lives is narrow and constraining, such that Black cultural expression - particularly expressions of Black pleasure - is “a thorny struggle.”

Representations of Black fun, frivolity and the luxurious freedom of leisure time spent in play remain relatively scarce. Instead, often portraying Black people as dangerous, angry or as threats to the social order (including a range of known and damaging negative stereotypes), representational conventions for the depiction of Black life and leisure remain ridiculously impoverished, stereotypical and frequently racist.

Representations of Black fun, frivolity and the luxurious freedom of leisure time spent in play remain relatively scarce.

As such, the “leisure divide” made visible in these games should not surprise. Instead, it helps us see the ways board games are yet one more facet in the material life of a nation that reflects and reinforces damaging stereotypical notions of race and class identity, and the ways leisure activities reveal much about who we are, and who we imagine others to be.

This article was originally published under the title of "The Leisure Divide: Board Games and Race" in the essay collection Playing Place: Board Games, Popular Culture, Space, edited by Chad Randl and D. Medina Lasansky. Copyright 2023 MIT. Reprinted with permission of The MIT Press.