“It is not yet known in society that the game is something very special”: Tikal, El Grande and 6 Nimmt! creator Wolfgang Kramer

One of board gaming’s first celebrities reflects on designers’ rising recognition.

Wolfgang Kramer is one of board gaming’s most celebrated creators, with a record five wins of Germany’s prestigious Spiel des Jahres prize to his name and credits that span from racing game Downforce (originally released as Tempo) to the hugely acclaimed Masks trilogy of Tikal, Java and Mexica released at the turn of the millennium.

The German creator was one of the first board game designers to earn name recognition both inside the industry and out, spurred by the widespread success of his games and their innovation - the scoring track that runs around the outside of a board, a now-commonplace sight, is known in Germany as a Kramerleiste in recognition of its debut in the designer’s 1984 title Heimlich & Co.

One of the first board game designers able to make a full-time career out of his work in 1989, Kramer sought similar recognition for other designers, lending his signature and support to an agreement between a number of star tabletop creators in 1988 to refuse a publisher deal unless they were given credit on the box.

With almost five decades and over 100 board game designs under his belt, and no sign of slowing down yet, I caught up with Kramer to discuss how things have changed since he first helped bring board games into the spotlight

How did you first get into designing board games?

As a teenager, I sometimes added new rules to purchased games. These modified games were played in my circle of friends rather than the original. That's why my friends asked me, "Why don't you make a completely new game?" This idea took root in my head. More than 10 years later, I had some time and I developed my first game Tempo, the predecessor of Top Race and Downforce.

How have your design philosophies and interests evolved during your career as a board game designer? Are there themes and mechanisms you are still yet to explore, but are keen to experiment with in the future?

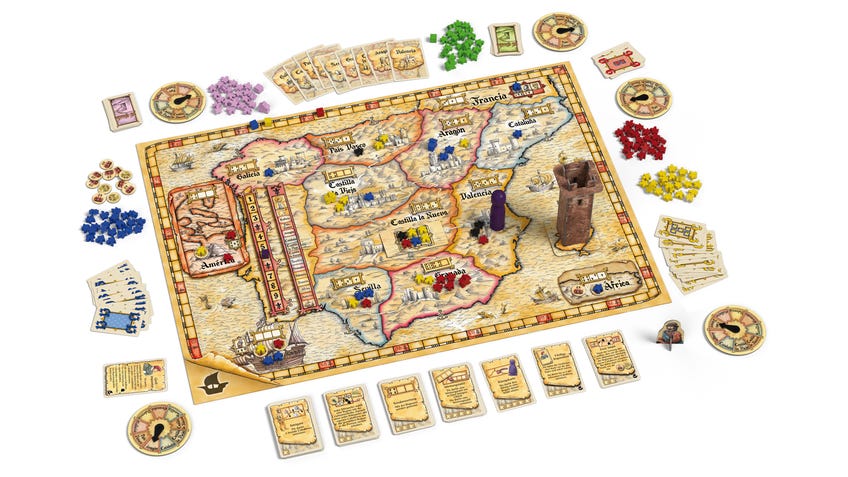

In the beginning I mainly developed family games, often with up to six players and more. About 20 years later, it was sophisticated adult games, such as El Grande, Tikal, Torres, Mexica, Java, Fürsten von Florenz [The Princes of Florence], Maharadscha [Maharaja], Colosseum. But there were also simple family games like Hugo das Schlossgespenst [released in English as Escape from the Hidden Castle], Verflixxt, 6 Nimmt!, Hornochsen [6 Nimmt! sequel Take 5!], Einer ist Immer der Esel [released as Who's the Ass?], Top Race. I like these types of games very much and would like to develop them also in the future.

When I made designing games my main job in 1989, I set out to create at least one game of each game genre.

Working with co-authors requires more teamwork. [Masks trilogy co-designer] Michael Kiesling, for example, likes to develop abstract games. That's why some abstract games were created. When I made designing games my main job in 1989, I set out to create at least one game of each game genre. This I have also implemented. I created communicative and cooperative games, reaction and skill games, action, bluffing and skill games, two-person, tactical, strategy, psychological, luck and exit games.

The only things I haven't developed yet are gathering card and roleplaying games and some games with novel mechanisms like deckbuilding and legacy games. A deckbuilding game will be released in 2022.

You were one of several German designers who at 1988’s Toy Fair in Nuremberg signed a coaster agreeing not to sell a design to a publisher unless the designer was credited on the box. 30 years on, what are your thoughts on the public recognition of board game designers today? Do you still feel like there is work to be done in terms of acknowledging those involved in creating board games?

The game designer is much better known today than in the past. There is hardly a game today where the game author is not mentioned on the box and in the game rules. This is a welcome progress. Nevertheless, there are still clear differences compared to the book author. You can see this when you look at the books. Here, the author's name is often larger than the title. You also see this at readings or when books are presented in daily and weekly newspapers and magazines, as well as at book fairs. But more important to me than the name of the game author is the image of the game in the population. Some progress has already been made here, but there is still a lot to be done. The game is by no means as well regarded as the book, or the music, or the film. You can see this in the media, in the press and on TV.

More important to me than the name of the game author is the image of the game in the population. Some progress has already been made here, but there is still a lot to be done.

It is not yet known in society that the game is something very special. Unlike the book, music and film, the game is a genre that is different every time. Books, music and films are the same every time. With the game, the process is different every time. You never know how it will end and who will win. In a game, in contrast to a book, music or film, you have to be active. You are a participant and influence the course and the end of the game.

The game is like a small world in which the laws - rules - are predetermined. In this small world, the players plan, act and move as they wish. They influence this small world, change it - as far as the rules allow - and control the course of the game.

You are credited with introducing a number of influential design concepts to board games, including the scoring track that runs around the outside of a board game (Kramerleiste) as in Heimlich & Co. Is there an invention or idea of yours that you wish had become as commonplace in board games, but has not?

I don't care if new mechanisms of mine are adopted by other designers or not. Therefore I do not follow this. For example, I know that the action points from Tikal were not taken over by any designer.

The mechanism of my two exit games Palace of Riddles and Riddle of the Pyramid (1995 and 1997) was not adopted by others at first. Much later, with a similar mechanism, they became the successful Exit games.

You are as well known for your solo designs such as 6 Nimmt! and Top Race as you are for your collaboration with designers such as Michael Kiesling and Richard Ulrich. What is the appeal of working with another designer on a game? How does your design process change when you are collaborating?

The development process is much more lively when you develop a game with co-authors. There are intensive and fruitful discussions about the mechanisms. Both co-authors test independently of each other. There is more testing overall, which is good for the game.

Working with co-authors has many advantages. But there are also disadvantages. One of them is that you only get half the fee.

However, there are also situations where we disagree. Then it's a matter of convincing the co-authors with arguments. If this does not lead to a result, we test both versions until we have a clear result which version was better received in the tests. Sometimes there are also compromises.

Working with co-authors has many advantages. But there are also disadvantages. One of them is that you only get half the fee.

You have won the Spiel des Jahres a record five times, more than any other designer. What are your thoughts on recent trends among players and designers of board games, in terms of the designs that are being produced today and the games that prove most commercially and critically successful?

We have a two-tier games market:

[The first] market is for advanced and well-informed gamers who play often and frequently. This market is nowhere near as large as the market for casual gamers. Nevertheless, the market for advanced players is extremely important because it acts as a multiplier and can have a very positive impact on a game's sales. It also has a positive impact on foreign markets. This market is mainly interested in new, original mechanisms and prefers to pick this up. It acts as a motor for game development and always demands something new. Usually, a new trend emerges when a new mechanism is successful on this market and is taken up by the mass market.

I feel sorry for every good game that disappears from the market. This also applies to games from other game designers.

The second market is the mass market for casual gamers. In this market, you can make very high sales once a game has become a brand. This market is mainly interested in simple and fun games. It changes very little. However, it likes to adopt new mechanisms that are successful in the [first] market and are suitable for the mass market. This can lead to the emergence of new trends.

I am happy about every new original mechanism, because it takes the game further and makes it more popular and possibly brings new people to the game.

Your design for Tempo/Top Race was reimplemented as Downforce by Restoration Games. How do you feel about the idea of older designs being reimagined for a modern audience? Is there another game of yours you’d particularly like to see brought to a new generation of players?

I feel sorry for every good game that disappears from the market. This also applies to games from other game designers.

Many older games of mine are still being distributed. Others that disappeared from the market have come back quickly or will be re-released soon. Among others these are the following games: Maharajah, The Palaces of Carrara, The Princes of Florence, Asara, Pueblo, Colosseum.

You were one of the first high-profile full-time board game designers in the industry. What advice would you have for aspiring board game designers who are at the beginning of their career?

I would like to give young, new game authors three points of advice:

Test, test, test, with as many people as possible. It's better to test 10 times too many than once too few. Every test with new test partners brings new insights.

Today it is not enough to have a good game. It has to be excellent.

If all test persons say, now the game is good, then try to improve the game even more. Today it is not enough to have a good game. It has to be excellent.

Always try to find spectacular and original mechanisms for a new game.

What are you currently working on?

A new, simple card game and a new board game will be released in the fall. The board game is an optimisation game with simple rules. However, it is not easy to achieve really good results. With each new game the player learns and improves his performance.

In the first months of next year, a very nice three-dimensional family board game will be released, which always has new surprises in store.

Next fall there will be a deckbuilding card game and The Palaces of Carrara will have new, more complex rules that will lead to more challenges.

I'm also working on a cooperative 6 Takes! card game.