Indie video game platform Itch.io has given tabletop RPG designers a new way to thrive

Through kindness and community.

Tabletop roleplaying has exploded in recent years, but in 1974 when Dungeons & Dragons was first published as a set of three booklets, there was an element of risk as the RPG’s creators dove into uncharted territory. Their trepidation about the fantasy roleplaying game’s mainstream appeal was obvious in the fact that only 1,000 copies were printed in its first run. Little did they know they had nothing to worry about. Today, thanks to the popularity of actual play podcasts and YouTube series, more people know about tabletop games than ever before - and while D&D continues to thrive, it isn’t necessarily the be-all and end-all anymore.

Fast-forward over 40 years from Dungeons & Dragons' debut and the tabletop RPG landscape in regards to players, designers and publishers has changed dramatically. Print books still exist of course, but the roleplaying scene has been made vastly more accessible thanks to the availability of RPGs in digital formats. Online storefronts such as DriveThruRPG have altered the publishing sphere drastically by making both out-of-print titles and releases in regular circulation widely available across the globe.

Until recently, publishing on DriveThruRPG and a designer’s website were considered the best ways to release a tabletop RPG independently. Creators backed by large publishers could get their books on store shelves but, for a long time, DriveThruRPG was the place to go if you wanted to publish a game on your own. Itch.io has changed that.

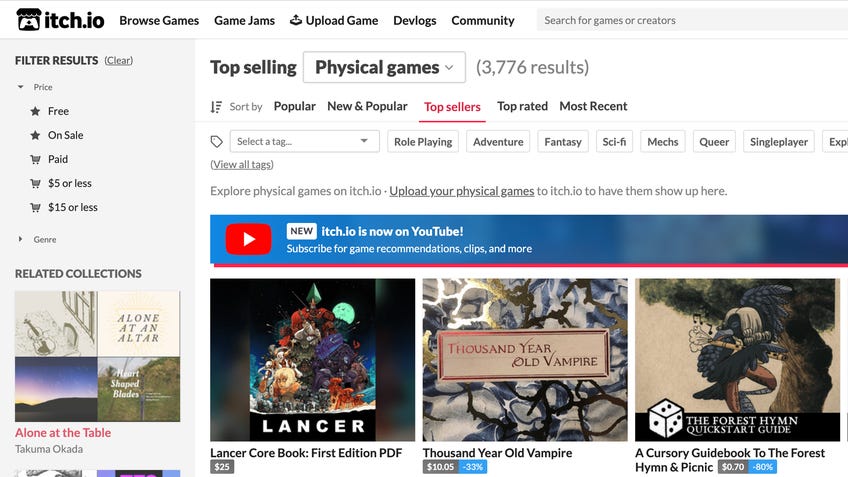

Itch.io is an open digital marketplace for digital creators that focuses on indie video games. The platform has come to prominence by putting greater power in the hands of the creators it hosts and taking an active stance against exploitative practices. It’s been around since 2013 but, recently, the site has been expanding beyond video games to encompass other media including fiction, comics and tabletop RPGs.

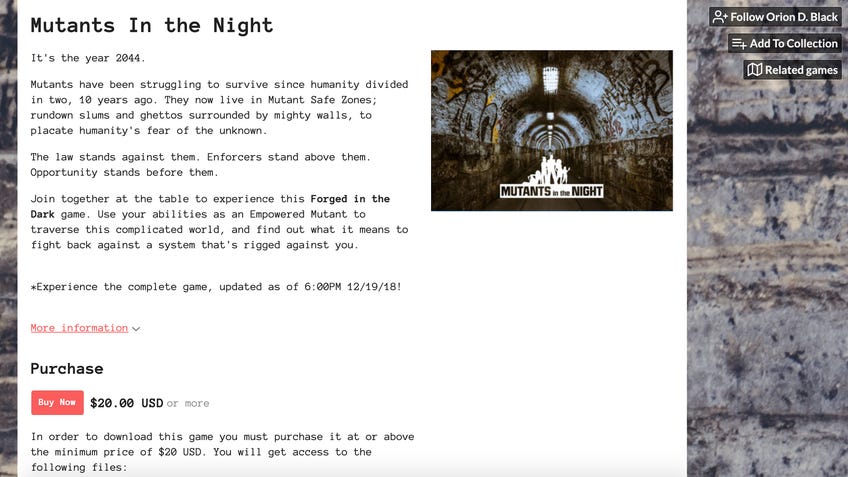

Orion Black, a prominent designer and activist in the indie RPG space, was one of the first to advocate for hosting on Itch, despite its larger focus on video games, because they felt it would help push smaller designers to start making a living wage from their games. Itch’s practices regarding price setting and revenue share looked like a way to make that possible.

“What really inspired me to speak out is very rooted in my experience as a black person in the mixed fields of art and business,” they tell Dicebreaker. “People, especially white people, berate people of colour when they try and hold themselves up to an appropriate capital value. This intersects with other marginalised people in TRPG, so I felt the need to both speak on that and take action.”

People have been able to supplement their income, or have an income, due to Itch.

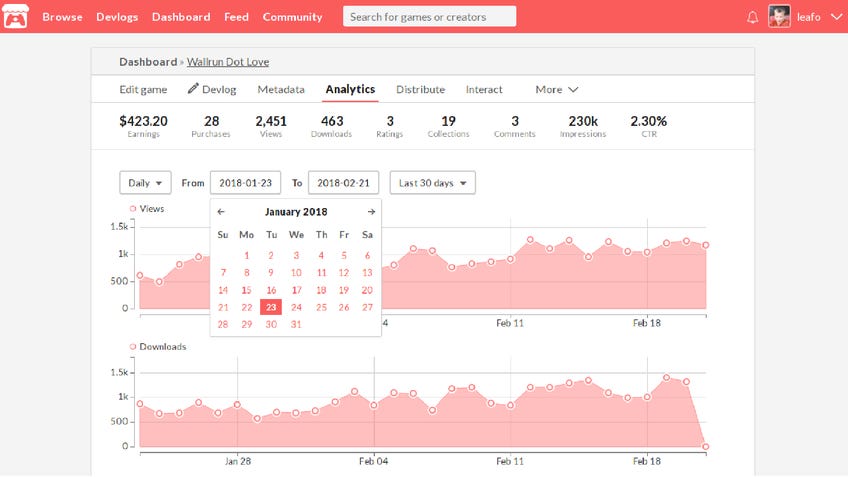

Black says that Itch provides detailed analytics - something that other sites do provide, but are typically much harder to digest. Along with better data tools, Itch also takes a smaller cut of designer profits than DriveThruRPG and the Wizards of the Coast-backed Dungeon Masters Guild, which take 30% and 50% respectively. Itch, on the other hand, allows designers to choose how much the site takes from their sales, giving them more agency in their businesses. Though Itch states that 30% is an “industry standard”, its cut defaults to 10% and creators can increase it from there if they’d like, giving easy credence to Itch’s reputation amongst the designers I spoke to of being more friendly and caring for those that use the platform.

The benefits are certainly plentiful but, for Black, the most important aspect is the revenue share and pricing model - something especially key for marginalised creators who may have less financial privilege than their peers: “People have been able to supplement their income, or have an income, due to Itch. That money not only goes into making their games better, hiring each other at fair wages and actually profiting, but also putting food on the table. It's amazing.”

While it seems that most indie designers still have to spread their wares across several sites, such as DriveThruRPG and a personal site, to ensure financial success, Itch.io’s backend suggests that competitors like DriveThruRPG leave a lot to be desired.

On a Discord call, Riley Hopkins, another indie designer and creator of tabletop RPG Interstitial: Our Hearts Intertwined, walked me through their dashboards on both Itch and DriveThruRPG. The differences were immediately obvious.

DriveThruRPG’s creator dashboard is basically a hub for links that will lead designers to different reports, analytics and ways to use their publisher points - a currency on the site creators receive based on their sales numbers - to run promotions. These promotions can include discounts and being highlighted on the site’s front page. Scrolling through the backend, Hopkins became more and more frustrated: “I have one game here; I have Interstitial. And then I scroll down and it's this mishmash of links that mean nothing to me.”

While Itch has several advantages over other digital RPG storefronts, not everything about the site is perfect. Although Itch provides the ability for designers to set the cut the site takes, easily view analytics and helps with tax time, Hopkins expresses frustrations with its somewhat fraught payout system. Payments can only be withdrawn seven days after a game has been purchased, and the time between initiating a payout and receiving it can be long and somewhat unpredictable. “Values may change as fees are being confirmed or refunds being processed,” Hopkins says, reading the fine print of their payout. “Amount should only be considered final after a payout is paid.”

This strange way of handling things like payouts is indicative of one of Itch’s biggest problems when it comes to the indie tabletop RPG community: the site simply wasn’t built with them in mind.

While DriveThruRPG can be clunky in aspects of its backend, it’s currently better equipped to help designers be seen - or at least more so than Itch. “They do do curation better, for what it’s worth,” Hopkins says in reference to DriveThruRPG’s categorisation of games. “Being able to be specifically about tabletop games gives them that ability.” Itch, on the other hand, is still fairly stunted when it comes to curation, especially for tabletop RPGs: “[With DriveThruRPG] I can open up a genre and I can go through that,” Hopkins continues. “Itch, I go to the ‘physical games’ section and it is just so much less.”

Though Itch still has some catching up to do in order to fully accommodate tabletop RPG designers, the community it’s begun to foster around independent creators is still a net positive for the scene. According to Black, the Itch team has been supportive of the efforts to make the site more friendly for the tabletop RPG scene: “The Itch staff have made efforts to help TRPGs grow on their site, but they're a small group and have a lot on their plate.”

To make things easier, Black volunteered their voice and insight to help facilitate communication between the tabletop roleplaying community and Itch staff - a role they no longer have to fulfil, thanks to some changes that have come to the site. “When the TPRG forums opened up on the site, others could directly voice their ideas directly without needing me as a conduit,” they say.

These forums haven’t been a hit for everyone - younger designers such as Hopkins have instead built their own communities in Discord servers and on Twitter - but they have helped tabletop designers adjust to a new site where they can not only host their games but also build a community. Mina McJanda, designer of RPGs including Voidheart Symphony, is one such designer, who’s been working on games since her time in university and was around during the Google+ days.

For several established RPG designers, Google+ became a hub of sorts for the indie tabletop community following the social media platform’s launch in 2011. The platform’s closure in early 2019 was a blow to the creators who had become used to using it - which made Itch, and all of its social networking-adjacent features, all the more appealing.

“When that [Google+] shut down, a lot of people were looking for new places to go,” McJanda says. “And, and it [Itch.io] was one of those places actually, because it does have these built-in forums where people can talk.”

When Google+ shut down, a lot of people were looking for new places to go. Itch.io was one of those places, because it does have these built-in forums where people can talk.

Other, typically newer and younger, designers had mostly been hanging around in smaller Discord communities, according to both Hopkins and McJanda; while they didn’t necessarily need Itch’s more social aspects, it did provide an avenue for the two groups to meet and interact more with each other and their own communities.

Despite some of the limitations it currently faces, Itch’s community aspects are among the elements that make it stand out as a publishing platform. There are two unique features that really drive this home: the ability to host game jams, and the option to offer free community copies to players who may not be able to afford games otherwise.

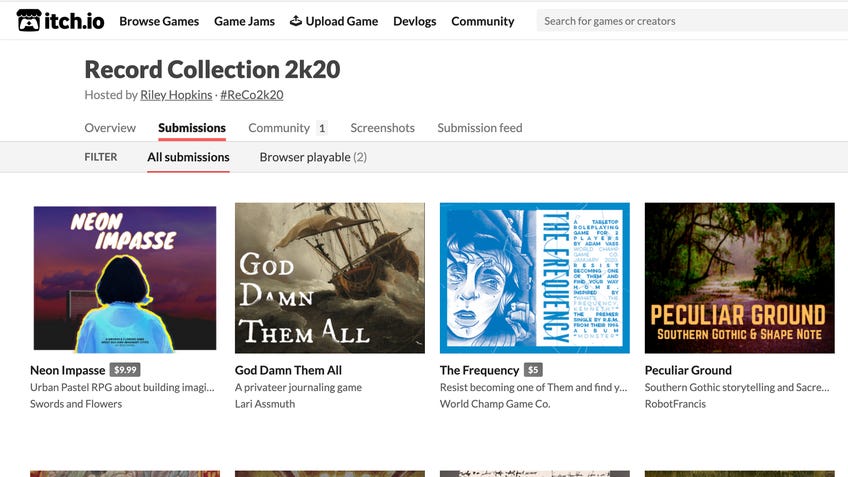

Game jams, which challenge creators to make a game inspired by a certain subject and often within a time limit, have been pivotal in getting new designers into the indie roleplaying scene. Events such as Hopkins’ Record Collection Jam, where creators make small games based on a song or album, and John R. Harness and Takuma Okada’s Emotional Mecha Jam have brought in at least a few RPG designers, including Viditya Voleti.

“I made an Itch page in, like, the end of January 2019,” he recalls. “And then I posted some of my first stuff there with the Sad Mech Jam, which I know a lot of other people also jumped in on the scene through that game jam.”

These jams, much like their video game counterparts, offer an easier, low-pressure way for creators to start dipping their toes into tabletop design. The attitude is more relaxed and focused on playing with creativity and cool ideas, rather than producing a super polished, pristine product, making it easier to encourage young or relatively inexperienced designers to try their hand at making games.

“It's the same energy as a video game jam where it's just, ‘Oh, I'm gonna make this little dumb idea, and I'm going to have fun with it and it's not going to be like, incredibly important that I crush it,’” Hopkins says. “You know what I mean? That doesn't need to be a finished product.”

Many indie designers are creating and posting quality, finished tabletop projects on Itch either because of jams or outside of them. Through community copies, the platform has also provided a way to keep RPGs accessible for any players who may not have the disposable income to use for games.

“Itch allows customers to receive free copy codes and download them, much like other sites. This wasn't the best solution, but better came along quickly,” Black explains. “A few community members discovered that sellers could create a pool of ‘community copies’ that anyone could grab for free. That's been the most popular effort thus far.”

Sellers can create a pool of ‘community copies’ that anyone could grab for free. That's been the most popular effort thus far.

Voleti has embraced community copies, saying “the process of putting community copies up is simple”. He runs his model as a one-for-one where a copy sold equals a community copy added to the pool: “So every like month and a half to two months, I'll go through my games to see what the total payments were and then I'll go to the rewards and then update it.” It isn’t a perfect system, but it’s more than many sites offer, and attests to Itch’s commitment to trying to keep people, rather than profits, at the centre.

Itch is not a fix-all for the indie tabletop RPG scene. It wasn’t built to support tabletop games natively, and the small team has a lot of catching up to do if they want to make it a truly viable platform for creators. But the benefits seem to outweigh the issues, as indie designers discover another avenue for publishing their games that offers a more equitable and community-focused approach. It may not be a perfect solution, but it certainly makes a strong argument for prioritising creators and audiences in a way that puts kindness first.