What D&D is to fantasy roleplaying, Traveller is to sci-fi RPGs - and its influence has never been greater, from Coriolis to Starfield

Venturing into the classic tabletop RPG that inspired Starfield.

Like Dungeons & Dragons, the original Traveller rules came in a small, digest-sized box containing three booklets. That’s about where the comparison ends.

Up to this point in 1977, all RPGs have one thing in common: in some way, they emulate or derive from the original Dungeons & Dragons design. Bunnies & Burrows rearranges the rules to portray a different power dynamic; Boot Hill introduces guns; Tunnels & Trolls works to make the core rules of D&D easier to use. For all of their tinkering, though, they remain D&D-esque.

Traveller is the first RPG that feels like a distinct game, free of D&D’s direct influence on its design. Traveller’s first booklet establishes character creation as a solo game unto itself, less interested in attributes (though it does establish them) than it is in creating the broad strokes of a fictional history. This grows out of the character activity mechanics established in Game Designers’ Workshop’s (GDW) earlier Musketeers-themed game, En Garde!

The player enlists the character in branches of the Imperium’s military, or for terms of service with the merchant fleet. Dice rolls then determine the results of that service by awarding and increasing skills, abilities, ranks and salary. In rare cases, a character can even die before ever being played in a group game! The player can repeat the process, with the character re-enlisting or changing careers, so long as they want to pay the numerical penalty for aging four years each go around.

Traveller is the first RPG that feels like a distinct game, free of D&D’s direct influence on its design.

Once the character musters out to find adventure, the player has a good idea of what the character has been up to and where their personal interests lie. This knowledge changes play in some important ways. The backgrounds convey a sense of the universe before the game even starts - there is an interstellar empire, a robust military, intergalactic trade and so on - and establishes the character’s place within it.

Compare this to D&D, where a character is defined by predetermined, abstract class characteristics; little, if anything, of the world, or the character’s connection to it, is conveyed. Traveller’s character creation mechanics represent a significant step in shifting the idea of an RPG character away from a sheet of numbers into something that more resembles a person who might have interests outside of crawling around underground tunnels, killing critters and stealing treasure.

Traveller’s career generator paves the way for approaches to character like Call of Cthulhu’s (1981) professions and Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay’s careers (1986), or even the optional rules in Pendragon (1985) that allow a player to establish the history of their character, their father and their grandfather in order to put down truly deep cultural roots. Cyberpunk’s life path system is also direct descendant. All of these examples show how the original iteration of Traveller sits at the head of a long line of design developments that emphasise the role in roleplaying, pushing the hobby toward storytelling and away from simulation-preoccupied wargaming.

This push continues into the second booklet, Starships. The second chapter is called “Starship Economics,” and it winds up teaching as much about the universe as it does the rules for space travel. The chapter boils down to the idea that starships of any size are incredibly expensive to build, buy and operate.

The original iteration of Traveller sits at the head of a long line of design developments that emphasise the role in roleplaying, pushing the hobby toward storytelling and away from simulation-preoccupied wargaming.

That expense centers the Traveller experience - a character can’t just go off gallivanting; fuel costs money, and so do empty staterooms and cargo holds. Characters have to marry adventure with a little bit of commerce, and that’s in the unlikely event that a space bank trusted a player’s character enough to extend credit to buy a ship. More likely, a character is part of a larger crew, working for wage or passage and subject to the whims of a captain, or their boss, the actual owner of the ship. All of these layers of fiscal responsibility create narrative friction and sketch in more detail about the universe before players can start plotting their own goals: who are these other crew members? Is the captain a jerk? What’s an interstellar bank like and how serious are they about getting paid on time? Isn’t time relative in space?

Again, there is nothing like this in official D&D products at this point - no wider world and no pressures of responsibility. Because there is no experience point system or real incentive to fight, Traveller opens vistas of potential to explore.

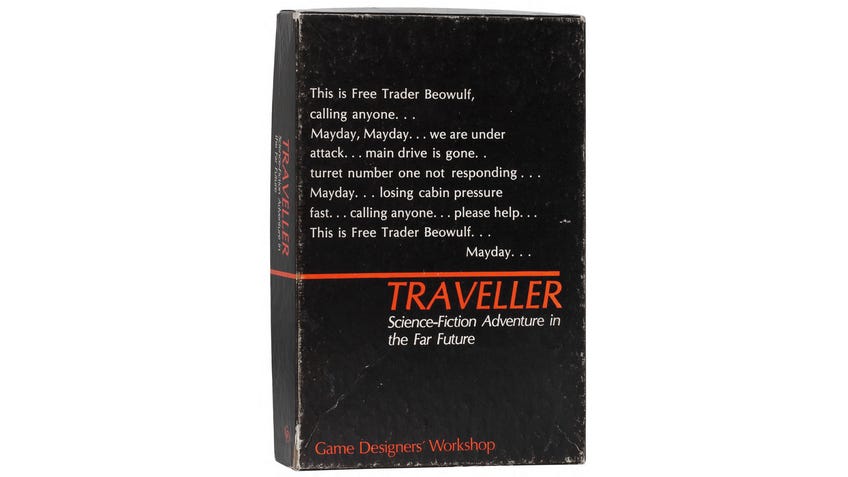

Unlike nearly every other RPG ever, Traveller imbues its sense of excitement and mystery through text alone. It has almost zero artwork in the core box set or the majority of the subsequent sourcebooks. Instead, the black box cover has words:

This is Free Trader Beowulf, calling anyone...Mayday, Mayday...we are under attack...main drive is gone...turret number one not responding...Mayday...losing cabin pressure fast...calling anyone...please help...This is Free Trader Beowulf...Mayday... Who is attacking the ship? Why? Is there time to save them?

The ship’s desperate message, printed in stark white letters on a flat black background, does more to excite the imagination than a hundred space battle paintings could.

The mechanics are simple for the time, as well. There is complexity, no doubt - space travel calculations require figuring out square roots and seeing that checkmark symbol in an RPG rulebook evokes the memory of traumatic summer school sessions of algebra class for a certain subset of players (or maybe just me). But the core is an easy roll-to-beat system - roll two six-sided dice, add or subtract the appropriate modifiers, and hope the result beats an eight. This feels featherlight and straightforward compared to Dungeons & Dragons; in fact, it has more in common with modern storytelling RPGs than any of its contemporaries.

Helping all of world building and approachability along is the fact that Traveller is the first RPG that lines up with the popular conception of science fiction as laid out in Foundation, Star Trek, 2001: A Space Odyssey and the just-released blockbuster Star Wars; there are spaceships to fly, planets to explore, aliens to encounter and adventures to experience, with plenty of mechanical tools to facilitate their creation.

In truth, though, while Traveller appealed to fans of space opera, its own inspirations are more firmly rooted in classic 1960s science fiction, like H. Beam Piper’s Space Viking (1963) and E. C. Tubb’s 33-novel Dumarest saga, which began in 1967, among many others. Piper’s novel (its importance to the game clearly signalled by the later New Era sourcebook, Star Vikings, 1994) gives Traveller its Sword Worlds, which are named after legendary blades. A number of the game’s features spin out of Tubb’s novels, but the most notable is the idea of High, Middle and Low passage, a key concern for space travel. High Passage is luxurious and reserved for the upper class; Middle Passage is for working crew, and Low Passage is a risky trip asleep in a cryotank, which has a 15% chance of resulting in character death!

Any game since that involves exploring the stars or interacting with complex technology builds on a foundation established by Traveller.

For the next few years, Game Designers’ Workshop released expansions in a series of little black books. Through these and the quarterly Journal of the Travellers Aid Society, GDW gradually filled in the details of their galactic empire. Soon, imperial military personnel were joined by mercenaries, scouts, merchant princes, robots, a variety of aliens and more, each accompanied by life paths and modular rules expansions. Individually, these expansions allowed players to mix and match options to find a level of complexity that matched their comfort level.

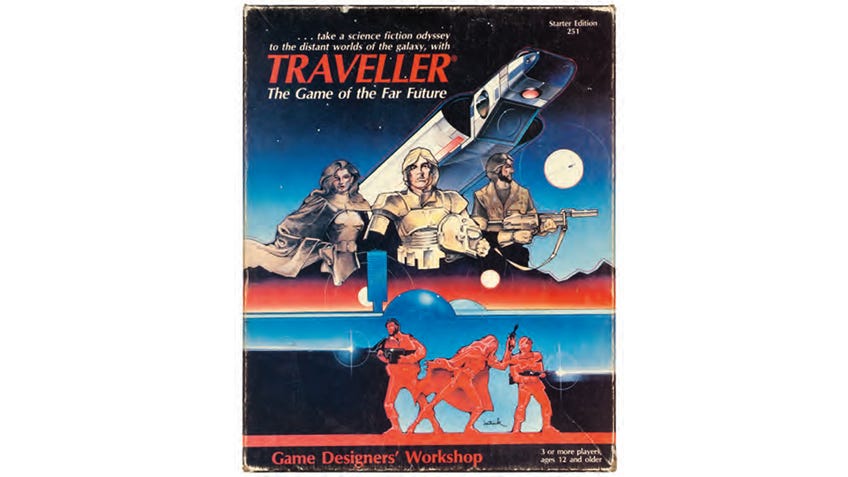

In 1983, however, GDW compiled many of those rules into the Traveller Starter Edition box set, a decision that proved to be the first step on a road that led GDW to focus on increasingly complex rule systems, starting with the notoriously fine-detailed military RPG, Twilight: 2000 (1984).

Subsequent editions of Traveller were mired in problems. The rules grew dense, and books were riddled with errors, requiring lengthy errata to be playable. Worse, there were narrative missteps. MegaTraveller (1987) tried to shake up the setting with the assassination of the emperor and the subsequent splintering of the Imperium into warring factions. Traveller: The New Era (1993) pushed the timeline further forward, past the collapse of intergalactic trade and a tentative re-establishment of the Imperium.

Both of these advances in the metaplot are interesting, particularly to newcomers, but tended to alienate players who loved the version of the Imperium they were already playing in (witness the success of GURPS Traveller, 1998, which consists of more than three dozen books that pretend as if the rebellion never happened).

Reactions among remaining Traveller players for The New Era were particularly mixed, but by then West End Games’ Star Wars: The Roleplaying Game was the top-selling science-fiction RPG. By 1996, financial issues forced GDW to close.

The original Traveller still stands as one of the most significant traditional sci-fi RPGs, thanks, in part, to its proximity to the dawn of the hobby, but also to both its scope and the crisp simplicity of its systems.

Any game since that involves exploring the stars or interacting with complex technology - Stars Without Number, Coriolis (2017), MechWarrior (1986), Rifts (1990), and more - builds on a foundation established by Traveller, including contemporary versions of the game, of which there are at least three! Mongoose Publishing (since 2008) and Far Future Enterprises (since 2013) both produce official versions of the game, while Samardan Press released their Traveller clone, Cepheus Engine, in 2016.

Away from the tabletop, Traveller is cited as being a key inspiration behind video games including this year's blockbuster release Starfield, with creative director Todd Howard acknowledging that the video game attempts to capture the harder science-fiction elements and cosmic exploration of the pen-and-paper RPG.

Traveller even has a ripping heavy metal concept album - The Lord Weird Slough Feg’s Traveller (2003). How many RPGs can boast that?

This is an edited extract from Monsters, Aliens, and Holes in the Ground: A Guide to Tabletop Roleplaying Games from D&D to Mothership by Stu Horvath. Copyright 2023 MIT. Reprinted with permission of The MIT Press.