The forgotten story of D&D creator TSR’s failed attempt to break into comics and become the next Marvel or DC

“DC Comics were very pissed off.”

TSR West was an attempt by the Dungeons & Dragons company to crack into comics in the late ’80s and early ’90s. At the time, the comics industry was griddle-hot. A successful expansion into the field would bring the company another revenue stream, perhaps one to equal the growing Book Department. Comics might also be a new path for people to discover D&D, and the company needed to expand its fan base. Finally, film and television were the searing-white nexus of mainstream culture at the time, and comic books are much easier to adapt to those mediums than roleplaying games. Get a good Forgotten Realms movie or TV show made and the future of the company might know no bounds…

These were all logical, laudable goals for the company.

But it would amount to less than nothing.

In the late 1980s, TSR licensed a number of its properties to DC, which made comic books based on them. The comics did well, selling on par with popular titles like Wonder Woman.

In short, the comics deal appeared to be a hit for TSR. It was exposing their brand to a new market and selling well for their licensee, DC Comics. DC put out a Gammarauders comic and a Spelljammer comic and was working on producing a Ravenloft comic written by Jim Lowder.

The plan was to create an overall comic book universe with shared characters and settings, just like Marvel and DC.

Perhaps this was the answer to TSR’s dropping sales. Perhaps it could become a company that created fantasy worlds and then licensed them to others. As the twenty-first century has taught us, comic books are ripe for translation into film and television. Perhaps DC Comics could have been a road back to the screen.

Of course, management would find a way to muck it up.

From former TSR designer Jeff Grubb’s point of view, TSR decided to go into competition with DC Comics over Buck Rogers.

Lorraine Williams, CEO of TSR from 1986 to 1997, was one of the owners of the Buck Rogers copyright. Now that TSR was working with DC to produce comic books, management wanted to see them make a Buck Rogers comic book. According to Grubb, the reaction of DC to the offer was a sarcastic, “Oh yeah, we’ll get around to that.”

Grubb said that with no Buck Rogers comic in sight, TSR decided to get into the comics business themselves.

The plan was to create an overall comic book universe with shared characters and settings, just like Marvel and DC. The comics could not feature Dungeons & Dragons material since DC Comics had that licence.

The old gods at DC Comics saw what TSR was doing and seethed.

Lawyers began to unfreeze their joints and gaze with mechanical eyes upon the contract they had made with TSR. The company licensed their properties to DC for use in comic books. Now, TSR was making comic books, thereby going into competition with DC. Was this a breach of contract?

The slow juicing and greasing of lawsuits commenced. While TSR was not going to publish any comics using AD&D or other properties that DC had the licence to, DC was still apparently furious. Steven Grant, the comic book writer involved in developing TSR West’s business plan, said that the comic book behemoth was “very pissed off.”

In revenge, DC cancelled every single AD&D comic book line, from the original eponymous comic to Grubb’s Forgotten Realms title and the still-in-production Ravenloft book.

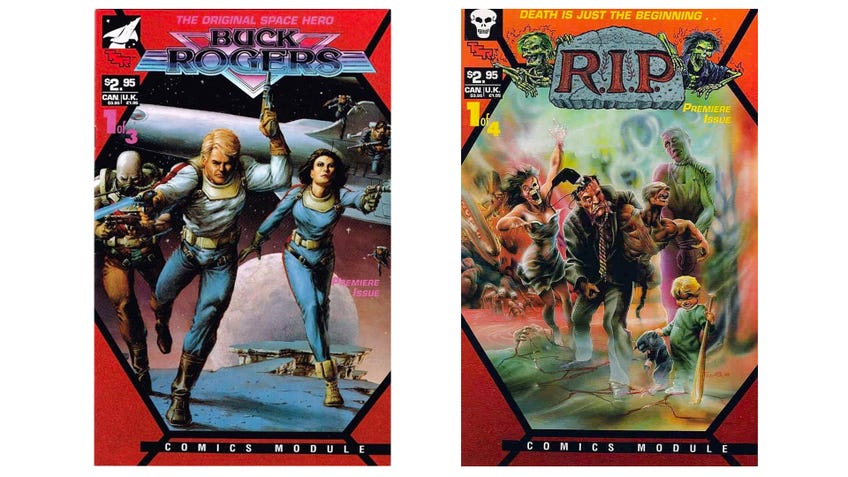

One of the changes imposed on TSR West by Lake Geneva was an attempt to placate DC Comics, and it went thus: TSR West would no longer make comic books. Instead, they would make “comic modules.” A comic module would be sequential graphic art, which is of course the definition of a comic book. But it would also contain a small game or role-playing material as well.

But the old gods at DC did not grow old by being fools. Though they saw through the flimflam of the comic module, they did not sue. They trod a different road to revenge. DC cancelled every single AD&D comic book line, from the original eponymous comic to Grubb’s Forgotten Realms title and the still-in-production Ravenloft book.

It all ended as quickly as it began. Brad Munson, a publishing veteran who worked with Dille and Grant to develop TSR West’s business plan, said, “The orders for the first three months were not all that great. And when the actual sales figures came in off the orders for the first two or three months of these comic modules that nobody understood, they pretty much killed the project.”

In Munson’s diagnosis of where the company went wrong, he fingers the decision to produce comic modules instead of straight-up comic books as “one of the things that led to TSR West’s ultimate and rather rapid demise.” The decision to call the products comic modules ended up severing the company from the very fans it sought to seduce.

Munson also faulted the company’s mediocre product as a reason for its collapse. He said, “The quality of the books themselves suffered from the very outset. I think if the books had been really good and the stories had been really strong and the art had been really hot, a lot of the other things that kept distributors away would not have mattered as much.”

TSR West is now dead and mostly forgotten. You can find the company’s comic modules for cheap on eBay, Amazon, and a half dozen other online comic book stores. They have not become valuable with time.

With thirty years of hindsight, this double failure looks like a disaster. Given that comic books have become the spawning ground of movies, and movies are such a leviathan of twenty-first-century popular culture, it is easy to imagine how things might be different if this deal had not collapsed.

If TSR had simply kept on with DC Comics, the AD&D lines could have served as templates for movies.

If TSR had simply kept on with DC Comics, the AD&D lines could have served as templates for movies. If the movies did well, this would have increased the value of the company’s intellectual property and, thusly, the value of the company.

In the end, TSR died because it wasn’t making enough money. Given what a cash cow the comic-book-to-film road has become, the failure of the company to step on to it due to the decision to break faith with DC Comics seems in hindsight a calamity. Fans are left to imagine what stories might have been with decades of DC-made AD&D comics for Hollywood to draw on.

This is an edited extract from Slaying the Dragon: A Secret History of Dungeons and Dragons by Ben Riggs. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin's Publishing Group.