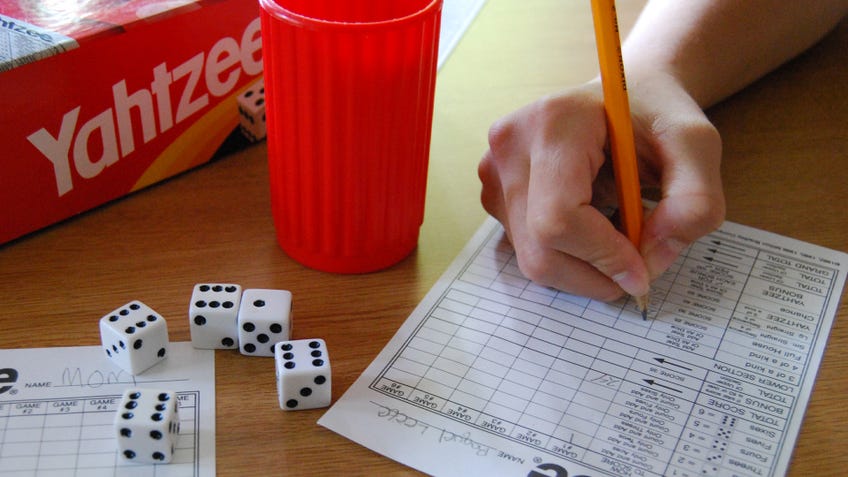

How family classic Yahtzee inspired board gaming's latest trend, the roll-and-write

Rolling with it.

Roll-and-write games have taken the tabletop gaming world by storm in the past few years. What started as an exercise in pure chance in dice games like Yahtzee has evolved into a game that puts players more in control of their own destinies. Today there are so many variations of this type of game - Welcome To, Railroad Ink, and Ganz Schön Clever (That’s Pretty Clever!) to name just a few - that it can be hard to keep track of them all, and the roll-and-write game has become one of the hottest tabletop gaming trends of recent years.

Chances are you already know a roll-and-write game, because Yahtzee is the template for the genre. In Yahtzee, you roll five dice and look for patterns of numbers to mark down and score. The patterns follow poker rules, where pairs, three-of-a-kinds and straights are what players want to see. You’re allowed to re-roll any number of dice two more times before you must score your roll. Each pattern is assigned a value on a scoresheet and every roll you must mark the score down on the sheet. If someone gets the same number on all five dice, they’ve just rolled a Yahtzee, which is the highest-scoring combination in the game. Yahtzee first emerged in the 1940s, before cementing its place as a classic family board game during the ‘60s and ‘70s.

The problem with Yahtzee is that there’s too much reliance on luck and almost no strategy to the game. Sure, you can choose between multiple options for what patterns to score sometimes but, really, you’re always choosing the one that will score you more points. Likewise, the re-roll mechanic adds a nice sense of risk and reward to the game, but realistically you’re going to be re-rolling dice that aren’t contributing to the scoring anyway, meaning player choice and strategy boil down to whether you have the right combination or not. Most of all, though, the biggest flaw with Yahtzee is the fact that each roll belongs to the player themselves and no-one else, bringing in a boatload of variance to a game already marked by high chance.

Dice games have evolved from Yahtzee’s luck-heavy experience to ones where the players have more agency.

Dice games continued to evolve from Yahtzee’s very luck-heavy experience to ones where the players have more agency. The first significant development in this evolution would be famed designer Reiner Knizia’s Decathlon, published in the early 2000s and still available to download for free from Knizia's website, which played around with scoring patterns in a very thematic way.

True to its athletic counterpart, Decathlon is separated into ten events with different ways to score points. Players take turns competing in each event, one after the other. Each one has different mechanics and scoring. For instance, the simplest one is the Shotput, where you roll one die at a time, stopping whenever you choose. If you ever roll a one, your attempt is invalid, and you score no points. Other events have similar elements of pushing your luck and fail states - Discus wants you to roll even numbers, Pole-Vault requires you to roll above a certain number and so on. Though it doesn’t give players as much freedom in how they can score, Decathlon injects some much-needed player agency when it comes to choosing when to stop. Rather than going for specific patterns of numbers, you only need to do the best you can while avoiding the fail states. That makes all the difference when it comes to the decision of whether someone wants to risk failing or go for an even higher score.

The ways in which dice were used changed as well. Instead of utilising the usual pipped dice numbered from one to six, board games started using custom dice.

Take popular civilisation-building dice game Roll Through the Ages, created by Pandemic designer Matt Leacock and released in 2008. The usual pips on the dice are replaced by symbols; instead of rolling for specific patterns or outcomes, you roll the dice and get the resources shown on the face that you rolled. From there, you allocate those resources to different tracks, boosting different scores and strategies in the process. This provides even more player agency to a game still defined by an instrument of chance. Resources can be used for multiple things, and different combinations of resources can be allocated to different strategies without railroading you into a specific one. Roll Through the Ages later saw a spiritual successor in last year’s Era: Medieval Age, which was dubbed the first ‘roll-and-build’ game by its creators as the result of introducing 3D buildings into the mix.

Today, we have a crop of dice and dice-adjacent games that combine these principles of push-your-luck and alternative dice to form the roll-and-write genre of games, but with one key element in common that hadn’t been true before: shared rolls. The roll-and-write games of today feature mechanics that rely on every player utilising the dice of a roll at once. One of the modern roll-and-write games most like Yahtzee, Ganz Schön Clever (That’s Pretty Clever!), has players rolling a set of traditional six-sided dice, one player at a time, and allocating them to different scoring tracks. The player who rolled the dice chooses what dice to use, then the leftovers are available to the rest of the players to allocate as they see fit.

Part of the fun of the roll-and-write is showing each other your score sheets and seeing what everyone did differently to you.

Better still is Welcome To…, a diceless roll-and-write (sometimes called a ‘flip-and-write’) that uses cards instead of dice to give players certain combinations of numbers and symbols, which then must go on a score sheet made to look like an idyllic neighborhood. Everyone is working with the same combinations of numbers and symbols, so theoretically they could end up at the exact same endpoint as someone else, but that never happens because there’s so much player agency and many different choices to make. Part of the fun of the roll-and-write is showing each other your score sheets and seeing what everyone did differently to you. This is thanks to how many ways you can use the values you’re given, with multiple strategies open before you. Seeing someone else do what you almost did makes for scintillating post-game conversation.

This is amplified even further when you’re given something closer to representing real structures rather than numbers and symbols, and build something tangible to show everyone else. Both Railroad Ink and Avenue boast this achievement. In each game, you’re given a set of roads and railroads of different shapes and properties - Railroad Ink has dice with different combinations of these roads and track sections on them, while Avenue uses cards like in Welcome To... It’s not really any different than filling in numbers on a sheet, but because you’re working with something tangible in the real world - here, roads and rails - it feels much more like you’re building something and, better yet, building something unique to you. Win or lose, you can’t help but take pride in your network of roads, as it’s been elevated from mere score sheet to a creation all your own.

Dice games have come a long way in their long history. From the popular yet drab game of Yahtzee has sprung such a well of inspiration, adding more and more player agency and strategy without toning down the inherent luck that makes dice games so thrilling. Roll-and-write games proper have had a big couple of years now. It’s exciting to think about where the genre will go in the future using games like Welcome To... and Railroad Ink as their leaping-off point. If we’re lucky, it can only mean good things.