If Quacks of Quedlinburg had a better name, it could be the next blockbuster board game

Plus a change in artwork.

I would likely have never known that Quacks of Quedlinburg, a board game about brewing potions, even existed if not for Alex Lolies. The once-Dicebreaker video producer has always been a keen supporter of the game, heralding it as one of their favourite tabletop titles of all time, and eventually introduced it to me via a version on Tabletop Simulator. Whilst having friends who also love tabletop gaming is generally a great way to discover new board games, I severely doubt I would have otherwise come across Quacks on my own.

Board games have been getting a lot more popular over the last decade, largely because of modern releases designed to get newer players into the hobby: think Azul, King of Tokyo and Carcassonne. Quacks of Quedlinburg feels like it fits so perfectly into this particular category of board game - which I’d like to be entered into the dictionary as ‘gateway games’ - because it embodies its most important aspects: accessibility and addictiveness.

When I recently introduced Quacks to my friend group they were initially intimidated by the number of components included in the box, worrying that this meant it would be a complicated game to learn. However, their fears were soon assuaged when we actually got around to playing. Because, at its core, Quacks is a game that taps into one of our most simple pleasures: being rewarded for taking a risk. It’s a more innocent version of gambling where the stakes are fairly low but the thrills are still very much there.

Over the course of nine rounds, players simultaneously and randomly pull tokens from their individual bags and place them onto their boards, which resemble pots for brewing potions. Tokens are placed on a track of bubbles, with the number shown on the token determining whereabouts it needs to go. For example, a token with the number three on it will be placed three spaces away from the last one. The further along the track a player gets, the greater the rewards.

This straightforward gameplay loop and the push-your-luck elements of Quacks makes it both a fantastic game to play and watch.

However, within their bags are also several white tokens which represent a particularly volatile ingredient which will cause a player’s potion to explode, costing them rewards and possibly their lives (in the narrative of the game, of course). Should the white tokens in a player’s pot add up to more than seven - when the numbers on the tokens are added up - then their potion explodes and they must choose between one of two rewards, instead of both. Players can choose to stop pulling and placing tokens whenever they want, with a cautious player ensuring that they gain both victory points and money at the end of the round.

Whilst victory points are counted and applied throughout the game - and ultimately decide the winner - you’ll often find players will take the money whenever they do explode, largely because it allows them to push the chances in their favour by purchasing more ingredients to put into their bag. Taking victory points may be the safer option, but think of all the non-white tokens you could buy with that money. Once players have recorded their victory points and/or purchased their ingredients, another round begins anew and they’re off pulling out tokens once again.

Whether you pull out exactly the token you were hoping for or the one you were dreading, both of these outcomes are guaranteed to provoke cheers or groans.

This straightforward gameplay loop and the push-your-luck elements of Quacks makes it both a fantastic game to play and watch. Even if you don’t quite know what’s going on, the steps are few and simple enough that it doesn’t look all that complicated. What’s more, is that Quacks is the kind of game that evokes very visceral emotional reactions in its players. Whether you pull out exactly the token you were hoping for or the one you were dreading, both of these outcomes are guaranteed to provoke cheers or groans.

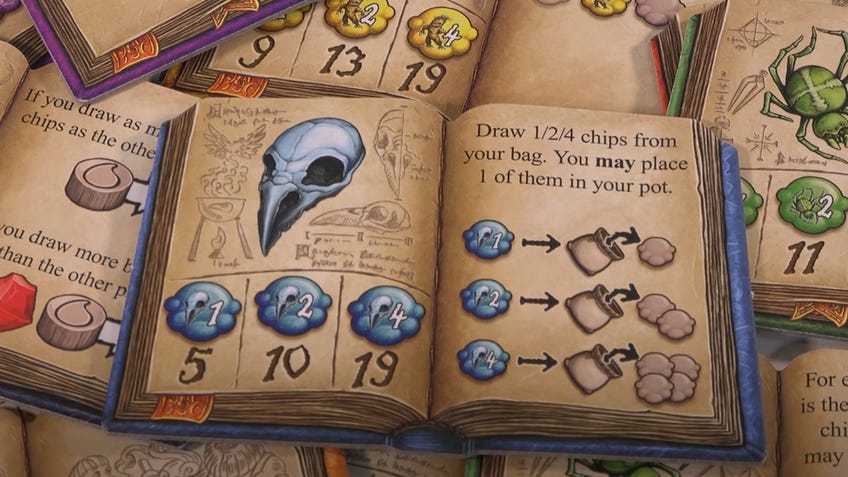

On top of all this, the components in Quacks are all wonderfully bright and colourful, with the cauldron boards having such a distinctive look that your eye is immediately drawn to them. Several of the ingredients also have multiple alternate boards determining what they do, meaning that you can shake up every game of Quacks by swapping in different boards and having players receive their new benefits.

The only explanation I have is that the game’s name and artwork are preventing it from reaching a wider audience.

And yet, despite everything that Quacks has going for it - the addictive gameplay, accessible nature, the colourful components and the replayability - the game continues to linger in relative obscurity. I’ve rarely heard people mention it outside of hobbyist groups and it’s certainly not sold nearly the same numbers of something like Azul - which surpassed over two million sales worldwide last year - which doesn’t seem to add up with the fact that it feels like the kind of board game that should be receiving mainstream recognition.

The only explanation I have - besides the threads of fate in the great loom of the universe simply not aligning - is that the game’s name and artwork are preventing it from reaching a wider audience. Quacks of Quedlinburg, whilst possessing some fantastic alliteration, doesn’t tell you much about the game besides the fact that it might involve ducks (which is a misunderstanding that I’ve witnessed happen multiple times). Its length and questionable interpretation makes for an overall confusing title that doesn’t draw new people in. Don’t get me started on the front cover’s terrible artwork either, which looks akin to an illustration for a cheap fantasy novel from the 1980s.

I believe that if Quacks of Quedlinburg was given a new coat of paint and a more appealing name, as well as a touch of marketing, it has the potential to join the ranks of the most popular gateway games of all time. Unfortunately, it continues to be one of board gaming’s most underrated modern classics.