Like chess? Here's why you’ll love its Japanese cousin, shogi

Generals interest.

Board games have always been popular, but over the last decade, they have exploded. There has never been a better time to explore the vast array of tabletop games available, from pen-and-paper RPGs spinning tales of sorcery and dragons and miniatures games of sci-fi warfare through to the most whimsical descriptive picture games. But throughout history one tabletop game has not only stood the test of time but remains a contender for one of the most-played games on the planet: chess. This ancient game of tactics has been a mainstay of people’s living rooms and professional circuits for hundreds of years, and you would be hard pushed to find someone who hasn’t at least attempted to play a match.

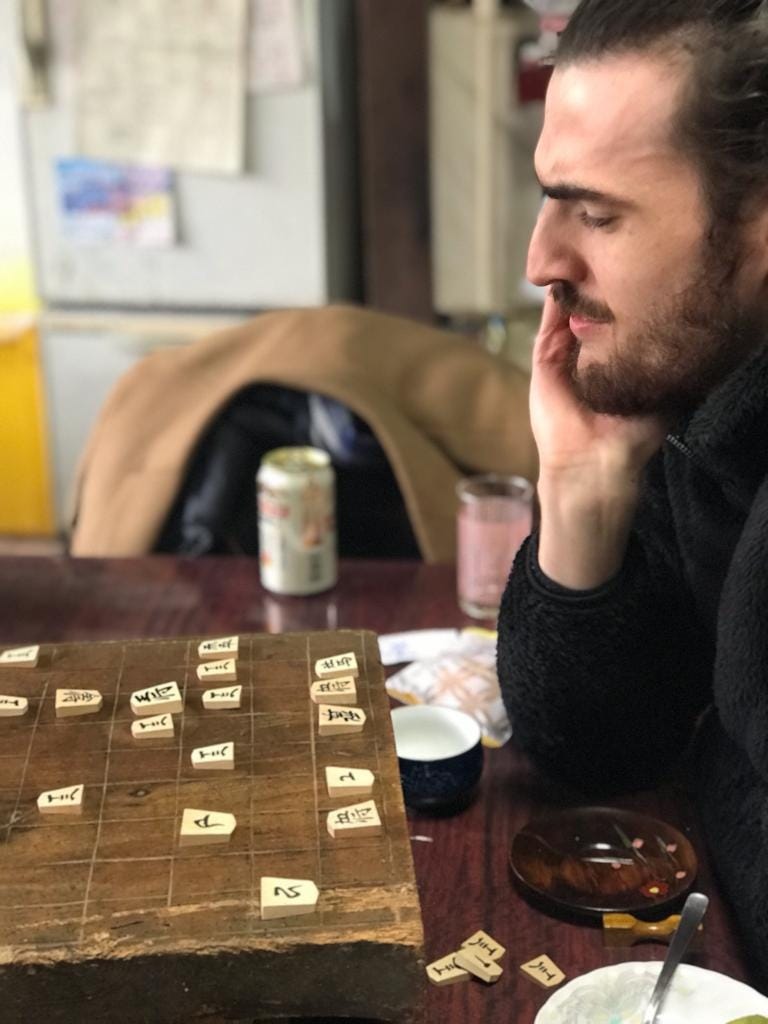

I, for one, love chess. I was always that child obsessed with board games for old people and chess sung out to me, to the point where I featured in a regional chess final. (I was heavily beaten and cried about it for at least a week.) So, when I moved to western Japan a year ago and a colleague asked me to play “Japanese chess” with them, I figured it couldn’t be too different, right?

Shogi directly translates as “general game” (? - sh?, ? - gi) and on the surface strikes an obvious similarity to international chess, the formal name of the chess we know and love: players have to checkmate the enemy king by manoeuvring pieces on a squared board.

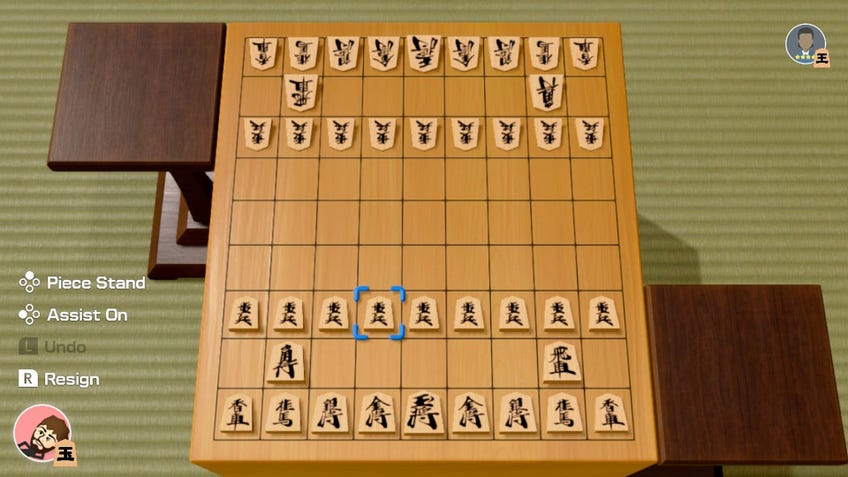

“Simple enough,” naive Michael said to himself as he looked at the nine-by-nine battlefield in front of him. Sure, it was a square bigger than international chess but nothing too daunting. That is until you actually see the pieces you are playing with. Gone is the towering figure of the queen and the crenellations of the rook, replaced with different-sized pentagons with various kanji (Chinese characters) written on them. There is also quite the personnel change, with one rook, one bishop and the queen replaced with two lances, two golds and two silvers, to leave a starting board of three rows of 20 ready-and-willing soldiers either side of the playing field.

There are, of course, many more differences between shogi and international chess, but the biggest difference not only took me by surprise on my first game but completely revolutionised my view on chess.

In international chess, once a piece is taken it is removed from play completely. If I were to use a war analogy, the sacrificial pawn dies valiantly on the field of battle. (In my mind it plays out a lot like that bit in Platoon where Willem Dafoe runs in slow motion with Barber’s Adagio for Strings swirling in the background, but then again I am odd.) So you can only imagine my surprise when, in my first match of shogi, said pawn reappeared on the enemy side like a good-for-nothing traitor. Here lies shogi's game-changing mechanic: the drop.

Taken pieces are not removed from play. Instead, they enter the opposing player’s hand to be used as and when the player sees fit, with very few restrictions. This simple rule fundamentally changes the way you approach the game.

In a match of international chess, it is common practice to offer pieces as bait in exchange for a bigger fish. In fact, many low-level games of chess boil down to a game of who can take the most pieces first. Shogi destroys this premise - and by doing so instantly slows the pace of the game. Every move becomes a deliberate action that has to be considered, as one false move could lead to a valuable piece being taken and used against you, or open up the king’s position too much for an opposing piece to sneak in and finish you off. At first, I was aggravated by this, equating this kind of loss to that kid who would goal hang at break time and claim to be top scorer. But the more I played, and the more nuanced drops I witnessed from my teacher, the more fascinated I became.

The drop mechanic can be used to turn the tide of battle in your favour at any given moment. If a sequence of moves will lead to a valuable piece being captured, dropping a piece in the way can immediately halt an enemy’s gameplan, making the opposing player reimagine their attack. Equally, a drop can place a powerful tool in a dangerous position, completely catching your opponent off-guard and forcing them to scamper back into a defensive position. In many games, I have been caught setting up a position in one part of the board only to get checkmated the moment I make my move by savvy piece placement from my teacher.

It is often said that the best chess players are thinking eight or nine moves ahead. In shogi, you not only have to consider your and your opponent’s next moves on the board, but also who might just come back from the grave to snuff you out. It’s captivating, addictive and often highly frustrating, but I always go back for more.

Needless to say, that one-time offer of a game soon became a weekly morning routine, which has spiralled out to playing in local tournaments and online matches to discover new manoeuvres to try and catch my teacher off guard (which never works, he’s far too streetwise to be hoodwinked by my new castling techniques). I am still yet to win a game against him, but whereas a young Michael was left in tears of pain and confusion at not understanding how he lost in a regional chess final, adult Michael is left awestruck at the creativity, intelligence and subtlety of the tactics displayed in Japan’s game of generals.