A natter of life and death: Playing ghostly board game Mysterium with a professor of parapsychology

Neuroséance.

We all like a good fright now and then. After all, there’s something exhilarating about sitting down with a group of friends, the lights turned down low, to play a truly ghastly game. For most players this will just be a bit of fun, but for others they may recognise in these titles their own unexplained experiences. With paranormal-inspired designs such as Betrayal on the House on the Hill and Ghost Stories so popular, what - if anything - can these games tell us about our own relationship with the afterlife? I sat down with parapsychology expert professor Nick Neave from Northumbria University and asked him to give me his thoughts on the classic séance simulator, Mysterium.

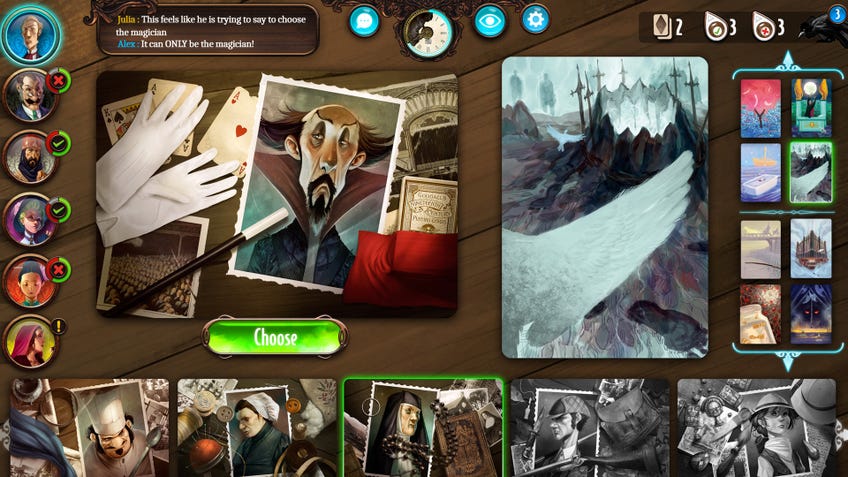

Mysterium, by designers Oleksandr Nevskiy and Oleg Sidorenko, is a cooperative game of ghostly deduction. One person plays as the ghost, unable to rest until their killer is brought to justice. The rest play as psychic investigators, brought together in a vast mansion to solve the murder. Over the course of seven rounds, the ghost guides the investigators on their way by dealing them a series of bizarre vision cards that help them work out who the murderer is, where they committed the crime and with what weapon. So far, so straightforward. The kicker comes when you discover that the ghost can only communicate with you at the end of each round when you make your guess: one knock for no, two for yes.

Neave approaches the paranormal with an open mind. "In my youth I was very much a believer; 100% believed in everything," he says. This changed when he went to university and studied psychology: "When I began to understand the brain and how people are tricked by illusions I completely swung in the opposite direction.” These days, and many research projects later, he's somewhere in the middle. "Paranormal experiences can be very profound and very life-changing," he says. "They can often be quite difficult to just explain away."

I loved how it mixed up two different traditions of communicating with the dead.

So what did Neave make of Mysterium? "I enjoyed it!" he enthuses. "It encourages you to be a bit thoughtful and a bit off-centre." For the professor, the real charm of the game lay in the central mechanic of giving each player a set of visions. "I loved how it mixed up two different traditions of communicating with the dead," he says. "Before spiritualism began in 1848, connections with the other world were through very subjective visions that were interpreted by a shaman or a witch doctor. Spiritualism changed that completely. With them it was much more pseudoscientific. You were asking direct questions to the spirits and I thought the game captured that well."

Mysterium is known for its evocative artwork that conjures the eerie and otherworldly feel of a haunted house. This is something that Neave noticed right away. "We all have in our heads this idea of what a spooky mansion is from years of gothic novels and Hollywood movies" he says. He adds that studies by researchers including Professor Richard Weisman conducted in Hampton Court and Edinburgh's South Bridge Vaults show that environmental surroundings play a big role in people's perception of whether they think a place is haunted or not. "The artwork really taps into that primal understanding we've all developed about these types of places," he explains. Neave smiles as he tells me that "it's almost ‘scar[ing] by numbers’ but it's done very well".

It's almost ‘scaring by numbers’ but it's done very well.

Mysterium is a game that only gets better the more people there are to play it. The interplay between the players as they try to work out what the ghost is trying to say is a "psychologist’s dream", according to Neave: "It's often the case that we believe the most confident or most glib person in a room." Any player who has been swayed by a know-it-all to give an incorrect guess against their better judgement will appreciate this all too well. As the professor explains: "Studies have shown that in a séance setting, people are often swayed by incorrect information." It's this susceptibility that helps make the experience all the more believable.

The game asks the question, "Is it possible to know that there is life after death - and, if so, how do we get that proof?"

It's clear from our time together that Neave really enjoyed the game - but would he use it to teach his students about parapsychology? "Absolutely," he says emphatically. "As a species, we're cursed with the knowledge that one day we will die. This characterises all human endeavour. This is why I love the game. It's asking the question, 'Is it possible to know that there is life after death - and, if so, how do we get that proof?’"

While it's obvious that Mysterium isn't based on any sort of scientific fact, it is revealing how much the board game relies on the tricks and tropes mediums use to create their performances. Mysterium certainly doesn't give us a window into the afterlife, but it does shed a light on our own desire to believe that there is something more beyond the grave.