Monty Python RPG creators on taking the piss out of D&D, letting players get silly - and why it’s not just Holy Grail

“Python’s approach was, 'Do what makes us laugh.' So we’ve made the game we want to play.”

The first thing you should know about the Monty Python roleplaying game is that it’s not just Holy Grail: The RPG. Well, mostly anyway.

“Our conception was always that we didn't want to make the Monty Python and the Holy Grail roleplaying game,” co-designer Brian Saliba tells Dicebreaker. “That's an easy thing to do. The simple thing to do.”

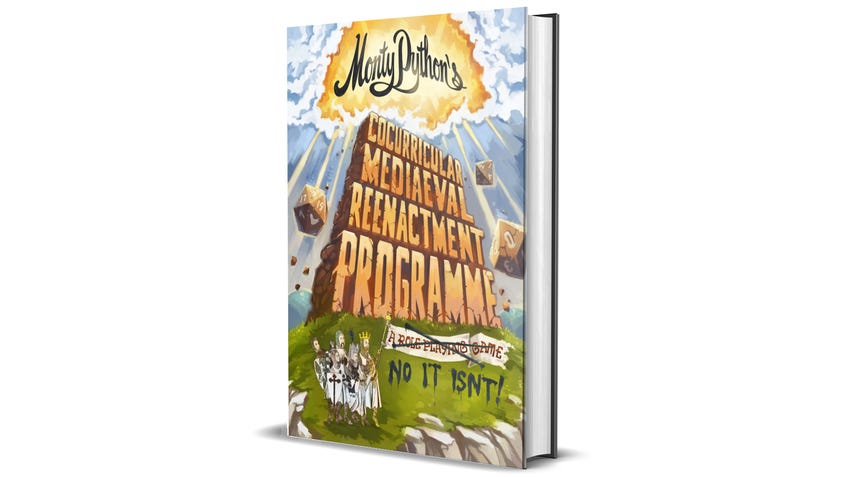

In fact, according to Monty Python’s Cocurricular Mediaeval Reenactment Programme - as the upcoming RPG’s cover proclaims itself in Life of Brian-esque stone letters - it’s not even a game at all. A banner dubbing it “A Role Playing Game” is crossed out, with “No it isn’t!” scrawled underneath.

It’s a distinctly Pythonesque contradiction (or should that be argument?), with a commitment to the bit that runs throughout the entire book: “Nowhere in the roleplaying game do we call it a ‘game’,” Saliba affirms. “It's always ‘the programme’.

“We very specifically look down on roleplaying games as inferior cousins of reenactment programmes - co-curricular reenactment programmes - which is what this is. This is coursework for students of English history.”

Jokes aside, the reality is a bit more straightforward. Monty Python’s Cocurricular Mediaeval Reenactment Programme is a real, playable roleplaying game based on the surreal sketches and characters of the British comedy troupe. In the works for a number of years - Saliba recalls an “agonising” period where the game’s future seemed uncertain - Cocurricular Mediaeval Reenactment Programme is finally headed to Kickstarter next month.

Saliba and co-designer Craig Schaffer are brothers and lifelong Python fans who spent their childhoods watching Flying Circus on MTV, impersonating accents and recreating the Cheese Shop skit at home. (“We’ve been working on this RPG for 30 years,” Saliba jokes.) Even so, they’re the first to insist that a Monty Python RPG needed to be more than an excuse to shout “Ni!” across the table.

“What we were adamant [about] is it can't just be replication of scenes from the movies and TV shows,” Saliba reassures. “Everybody knows the Black Knight scene by heart. So you don't just roll up and recreate that scene. It's not very interesting, and I don't think people would have much fun with that.

“It's more a matter of providing a toolbox of stuff that people can create stories that feel very Monty Python without recreating scenes. That's kind of a tricky thing, because it involves trying to figure out what makes Python stuff work and what makes it Python. [...] It’s a bit of a balancing act to try and find just the right amount of Pythonesque dissections versus just giving people a world, letting them see how it's built and letting them go from there.”

While there’s more than a touch of Holy Grail in the RPG’s mock-medieval setting of Middle Ages Britain - in place of classic D&D classes, players’ characters are oppressed peasants and ne'er-do-wells through to knights, troubadour and even royalty - the game’s world draws from across the entire Python-verse.

Life of Brian’s mistaken not-the-messiah has become the religious figurehead of Brianism, splintered into sects including the Order of the Gourd and the Order of the Shoe - itself divided into the opposed orders of the Shoe and Sandal, of course. A misplaced People’s Front of Judea and Judean People’s Front are chasing a lost legion of Roman soldiers unaware of the Roman Empire’s fall. And although medieval England is a little too early for the Spanish Inquisition to make an (unexpected) appearance, surveyors from the Spanish Preposition are busy gauging public interest in religious persecution.

It provides a toolbox of stuff that people can create stories that feel very Monty Python - without recreating scenes.

“We always wanted to have it be all things Python, using all of their stuff: the shows and the live shows, the albums and the books, and Spamalot, all of that stuff,” Saliba says.

“[But] we didn't want to have it set up where, it's a Monty Python roleplaying game, here's Holy Grail Land. Here's Life of Brian Land. And here's the Flying Circus Land. That didn't seem very fun to us. A lot of it is saying: how can we have this entire bizarre universe? How does it all weave together in medieval England?”

Layered on top of the medieval pastiche and absurd remixing of history is a knowing wink to Monty Python’s own gleeful smashing of the fourth wall and delight in toying with established ideas.

“It's very self-referential,” Saliba says. “There's stuff that happens where it's the equivalent of a character looking at the camera and saying something.”

In place of a dungeon master, a Head of Light Entertainment - a mixture of stuffy boarding school teacher and demanding BBC television producer - runs the show. The book includes around 20 different personas, each with their own interests and whims that influence how a session might play out - from the on-the-pitch action of a diehard sports fan to an anachronism-averse history buff who will punish the players for any out-of-time inaccuracies. The Head of Light Entertainment can themselves fall afoul of a table of dire consequences triggered when players push their buttons, receiving complaint letters from ‘viewers’ and ultimately being fired in favour of a replacement.

“That's one of the ways in which the game kind of subverts some of the expectations about how roleplaying games work; that the D&D DM or game master always has to be a completely impartial referee, and must always be balanced and carefully guide the game with a benevolent, all-powerful hand,” Saliba says. “This kind of plays on that a bit.”

Episodes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus began airing in North America in 1974, the same year that Dungeons & Dragons first appeared. The following year, Monty Python and the Holy Grail released - resulting in decades of roleplaying groups needing to answer me these questions three to cross a deadly bridge or encountering a killer rabbit in a cave.

Somewhat unbelievably, while no shortage of fan-made modules and homebrewed adaptations for the likes of Dungeons & Dragons exist, Cocurricular Mediaeval Reenactment Programme is the first official Monty Python RPG to emerge in the almost half-century since tabletop roleplaying was popularised. Not that it’s stopped the two from becoming closely intertwined regardless.

“Most traditional RPGs end up devolving into Monty Python quote sessions anyway,” Saliba laughs.

One can imagine what the Pythons would say about those people who were very, very serious and strident about their opinions about D&D. They would absolutely skewer them.

Perhaps because of their shared origins in 1970s popular culture and roleplaying’s reliance on stringent rules, Dungeons & Dragons and RPGs presented a natural target for Pythonesque lampooning. An earlier concept for the Monty Python RPG’s front cover was the iconic Foot of Cupid stepping on a game of D&D, while the designers joke about their original plan to publish seven 1,000-page volumes with “18 pages of very specific rules on how to climb a ladder” in an elaborate parody of convoluted rulebooks.

“[Roleplaying] felt like an area that could do with a slightly subversive send-up,” Saliba says. “Roleplaying gamers seem to take themselves very seriously these days. And if you talk about something that Python would immediately gravitate toward, it’s people taking themselves seriously.

“One can imagine, if the Pythons were aware of and active in this space, what they would be saying about those people who were very, very serious and strident about their opinions about D&D. They would absolutely skewer them.”

If it wasn't already clear, Cocurricular Mediaeval Reenactment Programme is not a serious game. Each of the five defining traits that make up a character slide along a scale between “Silly” and “Serious”, moving each of 20 possible traits - such as animal husbandry, chastity, argumentation and the ways of science - from their conventional definitions towards comical extremes.

“When it comes to authority, the serious extreme of that is you're authoritative and the silly side of that is splunge,” Saliba explains. “Animal husbandry; on the serious side, it's just animal husbandry. And on the silly side, well, it's animal husband-ry.”

As players “strewth” a critical hit or “spam” a one on their dice rolls, the traits shift up and down the scale, changing which die is rolled for tests. Hitting either extreme of a scale comes with the risk of a character taking things too far and triggering more dire consequences, at worst suffering one of the game’s “very frequent and easily obtained” fates, from arrest - much like King Arthur in Holy Grail - to death and alien abduction. Nothing is sacred: the world, characters or logic alike.

“Very much like Monty Python, there are moments in the game where you go completely anachronistic and suddenly an announcer in a peach-coloured tuxedo walks on with a microphone, or a penguin foot comes down from the sky,” Schaffer chuckles. “We thought it was very Python to not be stuck in just a limited framework, because that's certainly what their philosophy seemed to us to be: there is no framework that cannot be destroyed. No boundaries are solid.”

“I think everybody can use a little bit of silly,” adds Saliba.

Saliba admits that those hoping for a Monty Python campaign to replace their years-long D&D adventures may find it difficult to avoid the game’s potential for comic nonsense from causing eventual chaos. Even so, the wilful anarchy is somewhat channelled via specific quests - whether obtained from random NPCs or God himself - that provide the group with their latest grand adventure, from retrieving the Holy Grail (naturally) to curing the plague.

“We really want it to be a game that's conducive to sit down and one-shot; to have people over for dinner and then have a quick game - or a quick Cocurricular Reenactment Programme,” Saliba self-corrects. “Or actually have enough crunch to it that it can be played for a continuing campaign. You could certainly have a whole lot of sessions in pursuit of a certain quest.”

I think everybody can use a little bit of silly.

It’s in Cocurricular Reenactment Programme’s loving embrace of the ridiculous and nonsensical that its Python-obsessed creators hope it will channel the rebellious energy and comedy of Monty Python without becoming just another quote session around the table.

“It's kind of surreal - which I guess is appropriate for Python - to be working on this,” Saliba says. “It can be a little intimidating, even, because so many people love this stuff. In a way it feels like we have a responsibility.

“I always have to just stop myself, put that to the side and say: ‘Let's take the Monty Python approach.’ Their approach for making the shows and the albums and everything else was just, 'Do what makes us laugh.' That was what determined if something passed muster or not. So I've tried to do the same thing: put that aside and make the game that Craig and I would want to play.”