How an unassuming Magic: The Gathering token overtook one of its priciest star cards

Tarmogoyf, worth over $200 in its competitive heyday, will now set you back less than a common Goblin Shaman.

Nearly a decade ago, when I started playing Magic: The Gathering, one creature was famous for being, essentially, number one. The best stats for cost, the biggest meta share, the most iconic deck, the most demanded reprint, the highest price: Tarmogoyf was all five. During the Fate Reforged Pro Tour in 2015, it was the most played creature in Modern and, shortly after the tournament, commanded a price tag in excess of $200 - which is unheard of these days for a card still able to be reprinted. Since then, though, Tarmogoyf has fallen from the limelight - so far, in fact, that it was recently outpriced by a Goblin Shaman token creature. What is this Goblin Shaman thing? Why doesn’t it have a mana cost, or a real name? And the biggest question: why is it significant that one of these, specifically, has outpriced Tarmogoyf?

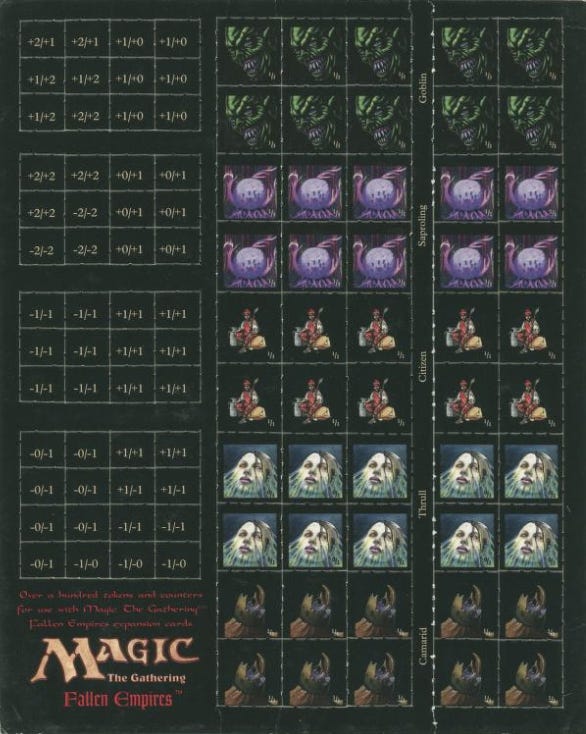

For the uninitiated: tokens are, basically, Magic: The Gathering cards that are made to represent things made by other cards. Magic’s first set contained a card called The Hive that sat on the battlefield and could be used to create 1/1 Wasps, featuring a suggestion to “Represent Wasps with tokens”. Back when The Hive was printed, this didn’t really mean much, just that something should be used to ensure that board states don’t get too confusing. Later, in Fallen Empires, caving both to practical concerns and the average tabletop player’s innate need to collect everything even remotely peripheral to their respective game, MTG maker Wizards of the Coast released a sheet of small, square tokens in magazine The Duelist. While adorably retro, they never caught on.

In 1998, tokens almost as we know them came into existence - specially-printed cards representing the creature types and colours of the cards that make them. (They didn’t have stats or text yet, as we hadn’t perfected the technology.) Funnily enough, these tokens were made in imitation of players. MTG designer Mark Rosewater, on a trip to Japan, saw that players were using beautiful cards to represent their tokens and decided to get in on the action. It was a good move; anyone who’s lost a chess piece and replaced it can tell you that it’s just not the same as playing with all your pieces being, somehow, ‘proper’. Players wanted to play the card game how creator Richard Garfield intended (even when he wasn’t the one who intended it).

Circulated freely in booster packs, most official tokens are common - but tokens are distributed in accordance with the frequency of cards that make them. Thus, when you have competitive staples that make unique tokens, you end up with sets like Dragon’s Maze, which was so underpowered, underdeveloped and generally unpopular that the most expensive card in the set was Voice of Resurgence, followed closely by its respective token. The Goblin Shaman token belongs to Fable of the Mirror-Breaker, multi-format all-star and the card that I sold at least four of at 50p a copy before it skyrocketed to twenty quid.

It’s natural, especially for tabletop players, to spend money on things with no practical value - and, more importantly, to let others know about it.

Yet, no matter what, tokens are still fundamentally like those Wasps: interchangeable reminders that can really be represented by anything you want. Pros on the SCG Tour would often opt for custom tokens that depicted top players. A player at my local shop uses a shiny Sharpedo Pokémon card for his Shark Typhoon tokens. In one particularly memorable craze, Canadian Highlander players playing Minsc & Boo, Timeless Heroes began scouring eBay for imported Japanese Hamtaro trading cards to represent Boo, Minsc’s pet miniature giant space hamster of Baldur’s Gate fame.

The point that I’m getting at is that once they take on any value at all, their possession becomes a powerful signifier of commitment. Typically in Magic, tokens are functionally worthless; they get freely passed around at limited events based not on price but on need. Once the outwardly ridiculous price point is established, adherence to it takes on its own value, whether that’s the market’s price on an official token or a self-imposed value (as in the Hamtaro example). When you hear that someone owns four copies of Fable of the Mirror-Breaker ($20/card), you might be nonplussed; Magic’s an expensive game, and it’s a competitive staple. If you see that someone owns four Fable tokens (~$8/card), you’ll think to yourself: “Man, they really love Fable of the Mirror-Breaker”. An expensive token and an expensive card approach price from opposite directions; for a Tarmogoyf, the price is an unwanted consequence, but for a Fable token, the price is the point.

So, here’s the crux: tokens, like any vanity piece, are signifiers of a willingness to spend. Everyone who plays top-tier red decks like Creativity or Scam in Modern has four Fables, because (as shown by Tarmogoyf), Magic: The Gathering players are used to spending loads of money on competitive staples. What Magic players are, usually, not used to doing is spending even a moderately high amount of money on cards that are, functionally, blank. This question - why are people spending so much on this token? - isn’t really resolvable within the logic of MTG, just the logic of life. People buy watches and, by force of habit, pull out their phones to tell the time; people buy shoes and take them off to walk when it gets dirty. It’s natural, especially for tabletop players, to spend money on things with no practical value - and, more importantly, to let others know about it.

The really ironic part is that Tarmogoyf may as well be a vanity piece too. The only format where it sees any play whatsoever is Modern, where it is at best fringe, and the only reason that Goyf carries a price point anywhere above dollar rare status is ingrained price memory. My guess is that, for most players who own a Fable token and a Tarmogoyf, the token gets out of the house a lot more. And if you’re buying something to wear out, you might as well make sure it’s in fashion.