Into the Odd is a far port from conventional tabletop RPGs that is well worth the journey

Coal-powered adventures in a land both fantastical and filthy.

In the Soviet science fiction novel Roadside Picnic, the Zone has been touched by the extraterrestrial, altered beyond comprehension by whatever was left behind, and then subsequently exploited by the global machines of capitalism and military imperialism. The pervasive weird suffusing the Zone calls to people who often end up sacrificing their lives in desperate bids to extract something, anything of value.

The Zone is home to anomalous forces, fantastical artefacts and scientific horrors. Cordoned from the morbidly curious eyes of humanity, it becomes the domain of soldiers, scientists and enterprising Stalkers - mercenary scavengers who have learned to avoid the worst of the Zone’s traps and earn pay fueling a technological black market. They treat the Zone with both a holy fear and loving reverence, a home and most likely a grave.

Chris McDowall’s Into the Odd, a recently remastered tabletop RPG, manages to filter Roadside Picnic’s Zone and Stalkers through a funhouse mirror version of industrial-era Great Britain and balances the whole concept on a suite of agile roleplay mechanics uninterested in mainstream assumptions. What will likely feel exceedingly commonplace to adherents to the OSR movement will feel downright otherworldly to those familiar with finding stat blocks in a, shall we say, manual of monsters.

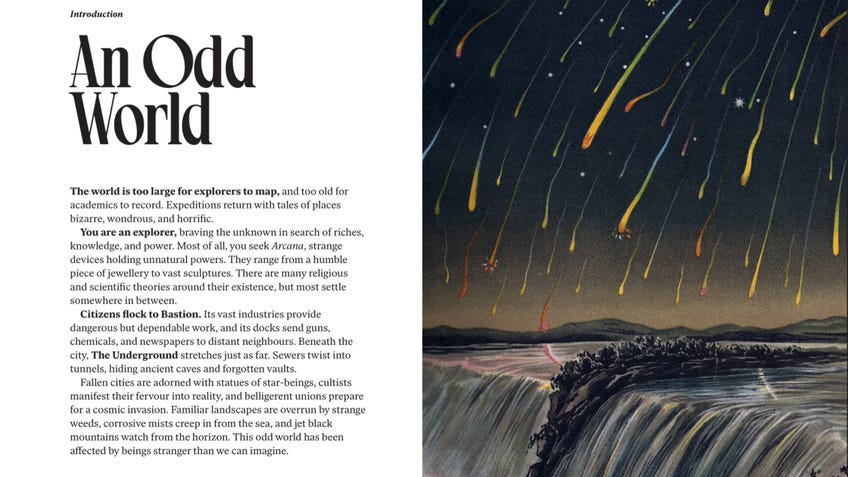

But there’s a deep irony with which McDowall presents the whole enterprise of adventuring. Bastion, explicitly “the only city that matters” according to the book, is only described as a smog-choked exporter of deadly weapons and propaganda. The often stupefyingly barebones text and peculiar (in the best ways) art design by Johan Nohr often feels like being told the ship isn’t sinking while fish swim around your ankles.

As a game book, Into the Odd boasts a lean 61 pages of rules text and worldbuilding - the rest of the 143 pages are dedicated to adventures and a lengthy appendix of random tables. It starts with an introduction to the world, a necessary adjustment of expectations away from discussing fall damage or how far away must a long be for optimum range. While the ‘What is an RPG?’ section might currently be falling out of vogue, Into the Odd keeps it brief and efficient - roleplaying is a conversation of questions and answers, and the players aim to “find treasure and avoid a nasty death”.

A quick way into my good graces is through a novel character creation system, and Into the Odd pulls a neat trick without sacrificing its dead simple, snap-quick style. Players roll three six-sided dice and assign them to three stats - Strength, Dexterity and Willpower. Your only other vital number value is HP - metaphorized herein as hit protection and smartly encompassing one’s ability to avoid injury - which at the outset will range between one and six. Just in case the severity of avoiding combat whenever possible wasn’t yet clear.

Players then cross reference their HP and highest stat on a table to determine their starting gear, which could range from a musket and fine, modern armour to a pigeon and debt. This loadout of three items is all the codified customisation the game offers. Everything else must be decided between group members and has no real bearing on how the Into the Odd plays at the table. There's not even a character sheet included in the book, though official ones do exist online.

Roleplaying is a conversation of questions and answers, and the players aim to “find treasure and avoid a nasty death”.

Speaking of, the influence of the OSR movement is most readily apparent through combat and is likely where the unfamiliar will feel they’ve been left at the terminal and missed their flight. If you fight, you roll damage (no roll to hit needed here!) and subtract the target’s armour. Sticky situations may call for a save, which you want to roll under the appropriate stat, certain attacks can damage a character’s stats until they rest, and the players usually act before everyone else. You might be tempted to flip back and forth, wondering if your copy somehow replaced words with more of Nohr’s esoteric scrapbooking, but Into the Odd wants the group’s time focused on solving puzzles and dodging traps, not referencing a character sheet and several books every turn.

Thanks to a successful Kickstarter campaign last year, the book comes packaged with two adventures that showcase two classic OSR staples - the dungeon delve and the hexcrawl. The Iron Coral is a sprawling, three-level example of the former, leading an expedition through soggy, salt-crusted corridors and deeper into the inexplicable reef jutting from the ocean. The Fallen Marsh details the miserable landscape just beyond this dungeon, allowing players to chase rumours and folklore, hunt down bounties and visit the nearby settlement of Hopesend.

The pages describing both are collections of room description and random encounter tables, a far cry from the more guided and structured modules that many Dungeons & Dragons 5E players have come to expect. It’s worth repeating that these are two very different approaches to the same basic principle at the heart of RPGs - collaborative storytelling. Into the Odd situates itself in a tradition of GM-as-referee: the characters ask them questions about their current predicament, the referee answers truthfully, and the players act as they see best. The situation changes depending on their actions, and the whole process repeats.

Into the Odd wants the group’s time focused on solving puzzles and dodging traps, not referencing a character sheet and several books every turn.

The magic, that subtle spice with which McDowall and Nohr have seasoned this dish derives from what is intentionally left out. This newer wave of rules-light dungeoneering sometimes called “post-OSR” relishes in the consequences of choice. One of the three main guiding referee principles (not PbtA principles, unless..?) is to present the players with “interesting choices that have a meaningful impact”. There is no failing to pick the lock, needing to pass a perception check or intimidating the right information out of the mayor in order to proceed. You adventure into the muck and mire of the world, experience some weird shit and try your level best not to die.

What, then, sets Into the Odd apart from any other OSR-inspired game? The Arcana, oft-deadly magical artefacts synonymous with the Zone’s anomalous tech is a nice touch, and McDowall’s trademark eclectic worldbuilding that, here, lands somewhere between Pratchett and Studio Zaum’s Disco Elysium is still fresh eight years after the first release in 2014. For my money, Into the Odd’s subtle satire of both its setting and the RPG power fantasy helps it stand out from amongst its peers.

There is no arguing that Bastion and the surrounding Deep Country are a loathsome, awful place from which the game offers no escape. From conception, the player characters will dive once and again into certain peril all for the chance of pulling enough cosmic detritus, arcane gewgaws and straight up viscera to afford a donkey and some soup. Advancing in experience requires the specific requirement of surviving expeditions - not looting gold, nor killing monsters - and later training an apprentice in your own reckless, extractive arts. It’s the core of colonial exploration turned inside out and soaked in coal fumes, its truth left naked and shivering without the protection of elf ears and noble kingdoms.

Into the Odd doesn’t use this criticism as a moral cudgel when players enjoy the delving - and the delving is indeed fun. Instead, like Red Schuhart from Roadside Picnic, it interrogates why a society that can build a fleet of warships and hoards blasting rods inside massive vaults would allow an entire class of people to trudge below the earth in search of more power. We all travel Into the Odd, but to what end do you go?