One of the best board games about war illustrates its futility

What is it good for? Money!

War is bad, right?

Not if you’re playing Mac Gerdts’ Imperial (or its follow-up with a different map, Imperial 2030). In both of these board games, war is profitable. Check out the introduction from the rulebook:

“Europe in the age of imperialism. International investors try to achieve the greatest influence in Europe. With their bonds, they control the politics of the six imperial nations: Austria-Hungary, Italy, France, Great Britain, the German Empire and Russia. The nations erect factories, build fleets and deploy armies. The investors watch as their nations expand, wage wars, levy taxes and collect the proceeds.”

In regular-speak: Imperial is a board game about being a shadow investor-slash-member of the Illuminati. It’s a game that is explicitly about financing imperialism. Each player is an “investor” that funnels money into different world powers, wages proxy wars and then slurps up all the profits.

It's one of the best board games about war ever made. And is it ever fun.

It’s an extremely cynical game. To understand why, and to understand how this game treats the topic of war, we have to talk a little bit about investment board games.

For the unfamiliar, investment board games are about, well, financial investment. They simulate the experience of a venture capitalist, where players attempt to invest their play currency in the future of an in-game enterprise. Often, investment games allow players to affect the outcome of their investments as well. Kind of like insider trading.

ANYWAY.

Many of these board games feature an aspect of shareholding. Some investment games even feature functioning stock markets, such as the 18XX series, and a smattering of them have cute little trains, including the recent Irish Gauge. All of them are capitalism on steroids.

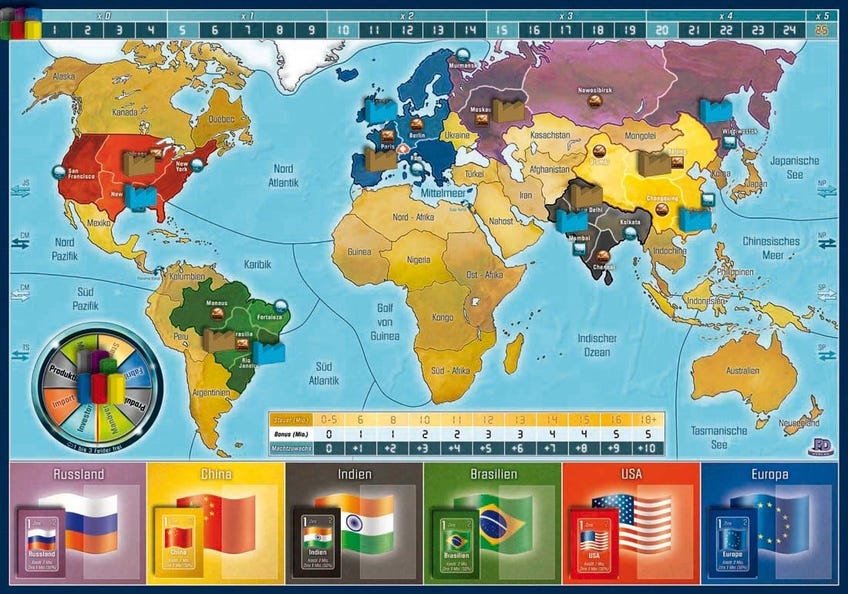

Imperial is relatively simple to learn, as far as investment games go. There are six countries. Each country has an independent treasury that players fill with money by purchasing bonds (shares) in that country; the player with the most share value gets to do various actions with that country’s pieces - fight wars, build factories and so on. It brilliantly abstracts the graph or grid of a typical investment game stock market track into a literal map of Europe.

Imperial was the first board game that made me think about what I was actually doing while I was playing.

By utilising the familiar face of a classic area-control board game like Risk, Imperial changes the metric by which players value their pieces. Instead of looking at who controls what, you’re looking to see which country is about to get the bear or the bull end of the market. Winning a game of Imperial is about learning to read the map/market, and timing your investments in different countries wisely. You’ll commonly have thoughts like:

Sure, Russia is doing great right now, but am I investing in it too late? It might lose that big brouhaha that’s brewing with Germany and I’ll get diddly squat when it comes time to get my interest.

The interesting argument that emerges from beneath Imperial’s surface is one about the intimate ties between capital and imperial power. Countries that don’t have money in their coffers can’t do much - they can’t expand their infrastructure, which in turn leads to fewer armies and a smaller board presence. The countries themselves have no agency, only the investors.

Whereas traditional investment games put you in the position of rail baron or nameless-shady-investor-person, most do not represent the human suffering and exploitation that is required to amass large amounts of capital. Imperial doesn’t have a blurb devoted to how war is bad in its rulebook, but the fact that you can increase your revenue by sending your soldiers to die pointlessly makes the point without ever having to state it. Imperial might as well be called Let’s Wage War for Fun and Profit.

Now, if the game stopped there, we’d already have something pretty cool on our hands.

But wait, there’s more! The mechanisms of Imperial work to add subtlety and nuance to its underlying argument about the futility of war. For instance, there is no luck in the game. Combat between nations is resolved on a 1:1 basis. So, if you come across my borders with an equal force to mine, we mutually annihilate each other. To play well in this board game is to be culpable in abstracted, meaningless violence. (You can also play peacefully, but that doesn’t happen often.)

The other uncomfortable thing about the way the board game works is the way that it ends. When a nation exceeds a certain level of value, the game ends and players effectively “cash-out” their countries with interest. But the final note of the game is that the ending feels completely arbitrary. Were that ending not instituted by a set of rules, the cycle of investing in countries, waging wars and gaining profits would continue indefinitely.

When I discovered Imperial as a teenager, it was the first board game that made me think about what I was actually doing while I was playing - maybe games were more than toys? Imperial isn’t didactic, screaming what it’s about as you play. “Come here,” it says, “make some money. Just don’t think about capitalism along the way.” *wink* *wink*