30 years on, fantasy board game HeroQuest is still inspiring modern dungeon-crawlers

From Gloomhaven to Star Wars: Imperial Assault, the legacy of a groundbreaking classic.

“From the moment the project landed on my desk I knew that whatever I did, it was going to be compared to HeroQuest,” former Games Workshop designer James Hewitt says of Warhammer Quest: Silver Tower.

“They were such incredibly formative games for so many people in this hobby, myself included. I'd have been mad to expect any different.”

The most popular board game in 1989, when dungeon-crawler HeroQuest released as a joint venture between family board game maker Milton Bradley and Warhammer creator Games Workshop, was Taboo. On the box of the party board game was an impressionist sketch of a grinning face framed in era-loud blocks of colour. HeroQuest, by contrast, boasted a hulking barbarian warrior, teeth gritted mid-sword swing, while orcs, zombies, wizards and dwarves had it out in the background.

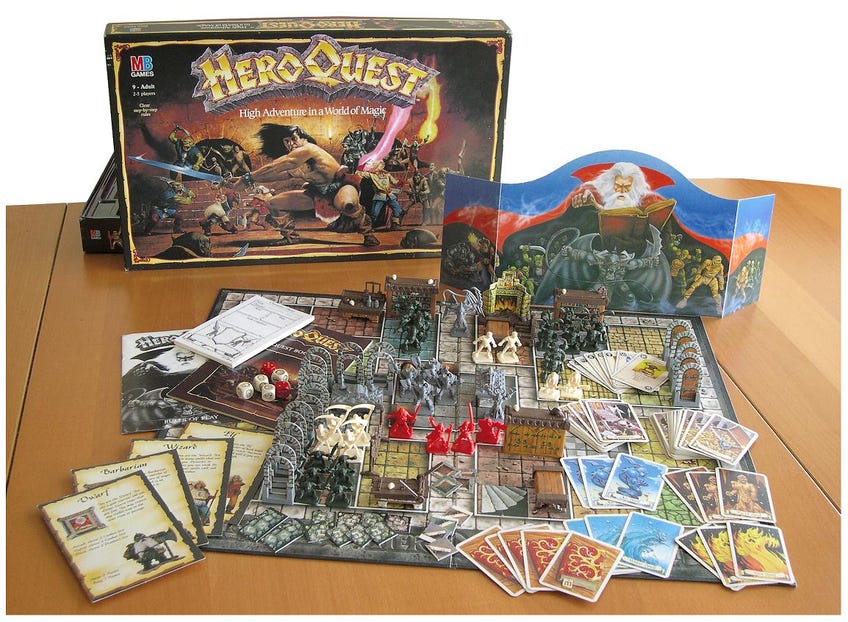

If the cover art stood out among shelves filled with Pictionary, Jenga and Trivial Pursuit, though, the contents of the box would really shake things up. Inside were portals not just to a fantasy land but, for many players, entire realms of roleplaying, miniature painting and worldbuilding. HeroQuest had equipment cards, and traps. It had experience points, and consistent campaigns. It had a DM’s screen, and the option for a fifth player to take the role of a game master. In short, it had everything needed to get a kid in the early nineties hooked on fantasy roleplaying for life.

“It's easy to forget, but back then you had to really dig to find out anything about nerdy stuff like this,” says Hewitt. “You had to have a friend who was into it, or hear about it at school (or work), or spot a special interest mag in a newsagent. Then, boom, there was HeroQuest, with its legendary TV advert and its presence on high street retailers' shelves.”

Though no doubt a problem for some collectors, there’s something oddly inspiring about browsing eBay for copies of HeroQuest today. It’s extremely rare to find one where the previous owner hasn’t had a damn good go at painting a few skellies at the very least, or scribbled their own dungeon maps in the blank pages at the end of the rulebook.

The rich artwork, the evocative setting - it was incredible.

HeroQuest was, Hewitt says, his first “proper” board game - not to mention his first dungeon crawl, experience with painting miniatures and taste of writing his own rules. Since 2016's Silver Tower, the designer has worked on several more dungeon-crawlers as part of the independent studio he co-founded, Needy Cat Games, including Hellboy: The Board Game and the upcoming League of Infamy. His original copy of HeroQuest is still up in his loft, stuffed with scribbled rules for new heroes, monsters and scenarios.

“The rich artwork, the evocative setting - it was incredible. I don't think I'd be doing what I'm doing today without HeroQuest!”

“I think there was definitely a large amount of influence from HeroQuest in Imperial Assault's DNA,” echoes Jonathan Ying, designer of Fantasy Flight’s successful dungeon-crawling Star Wars board game. “It naturally informed the development of its precursors - Descent: Journeys in the Dark and Doom - to a certain extent.”

When Ying was brought on board for Imperial Assault, one of the design maxims was “let’s make the kind of Star Wars game we’ve always wanted to play".

“This classic adventure and dungeon-crawling structure that started with HeroQuest was a big piece of the game's fundamental objectives.”

There was definitely a large amount of influence from HeroQuest in Imperial Assault's DNA.

HeroQuest’s popularity would result in several expansions and a 1991 sequel called Advanced HeroQuest. Although original HeroQuest shared some DNA with Warhammer - notably the black-plated Chaos warriors - Advanced HeroQuest was explicitly set in the Warhammer Fantasy universe, featuring an updated ruleset, some adorable Skaven friends and an even more emphatically gurning barbarian on the box. In 1995, Games Workshop released Warhammer Quest, cementing a formula for all-in-one boxed dungeon-crawlers. Tradition, of course, begs to be iterated upon.

“When I was working on Warhammer Quest: Silver Tower, there were two things I really wanted to 'fix' with the genre,” says Hewitt. “I'm not saying these weren't already games out there that had fixed this, but when it came to Games Workshop's dungeon-crawling games - again, HeroQuest and Warhammer Quest - I felt that these were recurring issues.

“First up, neither of them were great at presenting players with meaningful choices. You were pretty much relegated to ‘move forward, make an attack roll, see if it works’. There was a little bit of positioning and placement, and the cards/equipment you held might make a difference, but the majority of the game was pretty linear, from a gameplay point of view.”

Hewitt wanted Silver Tower - as a revival of classic Warhammer Quest - to offer players more control.

“Sure, there's still dice rolling - that was part of the brief; it was a Warhammer game, so it had to feel Warhammery - but by giving players a choice of up to four actions each turn as well as a central pool of additional actions shared by the group, the game introduced a lot more opportunities for the players to strategise around the table. I love table talk in games like this, and I see a lot more interaction between players in Silver Tower than I remember seeing in either of the other games.”

The tabletop roleplaying experience is one of the major things that dungeon-crawler games try to emulate.

The second change Hewitt wanted to make was the opposite of the first: predictable enemies. “Even when they were player-controlled, they were once again limited to ‘step up and hit a hero, or stand back and shoot a hero’.”

To remedy this, Silver Tower introduced ‘behaviour tables’ - lists of randomised AI behaviours, corresponding to rolls of a six-sided die. The behaviour tables, says Hewitt, “made each encounter play out differently, even though the enemies are controlled by the game, and it made each enemy type feel unique”.

“Cultists and Tzaangor don't just have different stats, they behave differently. In my mind, both of these things let the game feel closer to a tabletop roleplaying experience, which was always one of the major things that dungeon-crawler games have been trying to emulate.”

One of HeroQuest’s major innovations was to provide a gateway between board games and fantasy tabletop RPGs such as Dungeons & Dragons. It streamlined similar terminology and concepts, and, like a grizzled old veteran with a silver tongue, steeled young adventurers for their first steps into roleplaying proper.

“Gloomhaven was for sure inspired by other dungeon-crawlers, namely Descent and Mice and Mystics, which I'm sure were, in turn, inspired by HeroQuest,” Isaac Childres, designer of Gloomhaven, says of his acclaimed fantasy adventure. “Dungeon-crawlers definitely have a habit of relying on randomness to resolve combat. You attack something, you roll some dice, and you hope for the best. This is what D&D is all about, too, and its influences are everywhere. I wanted to instead create a game that was more focused on decision-making and forward thinking.”

HeroQuest did an amazing job of bridging the gap between Dungeons & Dragons’ full-on tabletop roleplaying and board games.

“I think HeroQuest did an amazing job of bridging the gap between Dungeons & Dragons’ full-on tabletop roleplaying and board games,” agrees Ying. “I think it certainly did a lot to set the tone for dungeon-crawling as a general practice, and the idea that you're diving into a scenario full to bursting with monster miniatures and you've got to use your cleverness and abilities along with some good luck to defeat the enemies and get the treasure.”

Ying compares HeroQuest’s influence on modern dungeon-crawling board games to the way Magic: The Gathering paved the way for the popularity of collectible card games.

“The core structure of it has permeated the culture to the point where you can even see its influence in games like Clank! or Burgle Bros, and of course modern behemoths like Gloomhaven.”

One of Imperial Assault’s most engrossing features was a ruleset for structured campaigns that took into account the players’ actions in past missions, affecting both narrative and gameplay elements in future encounters with the Empire. The idea of a persistent campaign has been taken one step further in legacy board games such as Pandemic Legacy and Gloomhaven, with the outcome of previous plays making permanent changes to a game’s board, components and narrative via stickers, destruction of components and player personalisation. Ying credits HeroQuest with introducing the concept of a connected campaign to board games.

“It is illuminating to see how far we'd come since the game's origin but it also impressed upon me how there was pretty much nothing like it when it came out. Sort of like the [Ford] Model T car; it's really not the best car you could be driving [today], but it was groundbreaking upon its release and all of our advances and knowledge we've gained since were built on its foundations.”

It was groundbreaking upon its release and all of our advances and knowledge we've gained since were built on its foundations.

“I have a lot of people who tell me that Gloomhaven reminds them of playing HeroQuest in their youth, and that makes them happy,” says Childres. “So, yeah, I think HeroQuest got into the hands of a lot of kids of a specific generation, and it certainly shaped their tastes. Now that they are adults, they are primed to enjoy other dungeon-crawlers like Gloomhaven.”

“It was a self-contained dungeon-crawling game in a box; my history might be a bit shaky, but far as I know it was the first example of this,” reflects Hewitt. “D&D had released its Red Box about five years previously [in 1983] which contained dice and maps, but I think HeroQuest was the first time you had so much stuff in one box. Miniatures, dice, cards and a pre-built campaign - it was a trendsetter.”