We’ve played the Elden Ring board game - here’s how it works, and what we thought

90 minutes in the Lands Between.

The first thing you should know about Elden Ring: The Board Game is that it’s not Dark Souls: The Board Game in a new set of armour.

While Dark Souls and Elden Ring share more than a few similarities on screen, Elden Ring: The Board Game is a very different beast to the divisive tabletop adaptation of its predecessor. Dice are out entirely, replaced by a new card-driven combat system - and even the Dark Souls board game’s celebrated node-based movement, used most memorably in its boss battles, has been left on the cutting room floor in favour of an ambitious new way of replicating the video games’ tense fights.

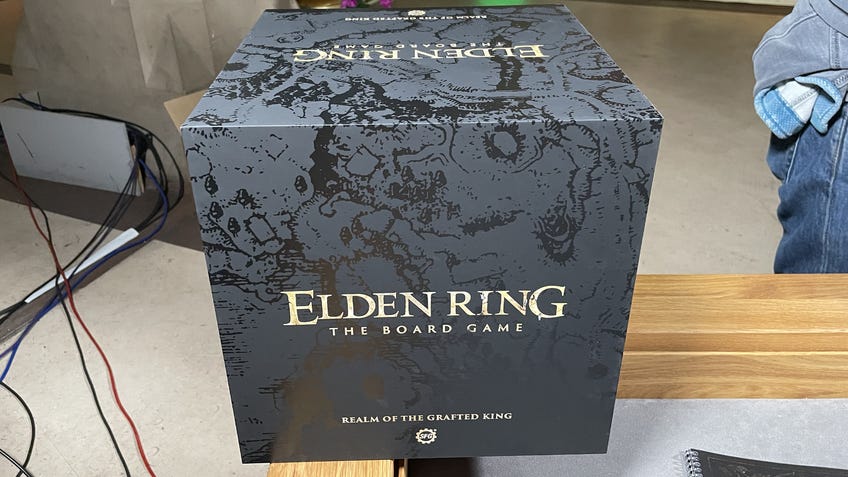

In short, Elden Ring: The Board Game is a brand new game from the ground up, hoping to capture the open-world discovery of the video game with some new tricks while also maintaining the series’ reputation for tough, punishing fights against ruthless opponents.

Dicebreaker recently had the opportunity to play a 90-minute demo with lead designer Sherwin Matthews, developer Fraser McFetridge and creative director Mat Hart at publisher Steamforged Games’ Manchester HQ ahead of the game’s November 22nd Kickstarter.

The demo was explicitly a ‘tutorial’ quest for Elden Ring: The Board Game’s first big (VERY big) release Realm of the Grafted King, taking our party of three Tarnished characters from our first steps into the core box’s region of Limgrave - which will be expanded to the rest of the video game’s Lands Between by future expansions and standalone sets - to a battle with the Beastman of Farum Azula, a boss encountered in the area’s Groveside Cave dungeon. Matthews pointed out that typical quests in the game would be more “chunky” than the stripped-down preview we were led through.

The aim is for exploration to last for around an hour, with the boss battle making up the final 30 minutes.

Like the video game, the Elden Ring board game divides its attention between open-world exploration and more focused combat encounters. Players build the map one tile at a time, revealing enemies, non-player characters and other icons they can interact with, in pursuit of a set of objectives. These objectives, known as Guidance of Grace, serve as the main narrative backbone of each session, needing to be completed to access the quest’s final boss showdown. The individual objectives encourage exploration and interaction, advancing progress for gathering resources, discovering specific icons and defeating enemies, and more besides.

They’re also a ticking clock to stop the players from wandering off too far into the open world and dragging out the game’s length; each round that passes without an objective token being placed on a Guidance of Grace card sees the players lose a Faith of Greater Will token - run out, and it’s game over. The aim, Hart says, is for exploration to last for around an hour, with the boss battle making up the final 30 minutes.

Individual turns move fairly quickly, with each player only getting three actions on their turn. In what will become a running theme, there are also three possible actions, which can be repeated: moving between tiles, exploring - revealing a new tile adjacent to your current one - or interacting with a token on your current space.

These tokens provide the flavour of Elden Ring’s world, representing elements that will be familiar to players of the video game - albeit adapted to fit the board game format. Map pillars must be reached to unlock a second stack of map tiles to explore. The Santa-like merchants offer the option to trade for item cards or gain a secret specific to each quest - including the ability to gain an advantage over the final boss. NPCs present new side quests in addition to the main objectives, which persist into future sessions and can seed new story events into other decks - the time pressure on the players means that not every mission can be completed in a single sitting. Collecting a Stake of Marika token adds an additional life to the group’s shared pool, spent if someone falls during battle.

Hoarding resources and completing quests is all good, but the meat of Elden Ring is found in its fights. Triggered when a player interacts with an enemy token on the map, fights cinematically move the action from the map board to a dedicated Quest Book of encounters - the number of the token determines which encounter you’ll be facing.

Similar to recent games such as Frosthaven and Stuffed Fables, the Quest Book is both rulebook and board, offering setup instructions on one side - a bit of narrative intro, objectives and details on what you’ll get for winning - and a gridded battlefield on the other.

This battlefield is where Elden Ring finds its feet, and highlights just how far apart it stands from Dark Souls: The Board Game.

The battlefield is where Elden Ring finds its feet, and highlights just how far apart it stands from Dark Souls: The Board Game.

Rather than acting like a conventional grid map to reflect the positions of miniatures, the grid represents both physical position and each character’s stance - a key part of Elden Ring and the Soulsborne games before it. The board game’s stance system aims to translate the tight timing windows and attack-dodge-block rhythm of the video games into a physical representation across three rows, roughly representing aggressive, neutral and defensive stances.

During fights, characters are able to move across columns - which effectively determine attack targeting and range - and between rows, switching between different stances. A more aggressive stance might grant the opportunity for extra damage to an enemy, while the neutral row allows a character to manipulate the timing of their attack by changing the turn order of combatants, and the defensive back row provides bonus defence and the chance to draw more cards. Like an exploration turn, players get three actions from three choices: move, attack or draw a card, keeping things tight and the rules easy to grasp.

It’s a well-considered system that works fluidly in motion, cleverly streamlining the idea of timing, position and stance into a single square on the board. In our demo fight against a couple of Godrick Soldiers, it managed to feel pleasingly tactical without becoming bogged down in fiddly rules. Helping combat feel pacey is the way it slots comfortably into the exploration; only the player that activates the token enters the battle, and takes their turns while the rest of the group continues to explore. (Additional players can join them by spending an Effigy of the Martyr token collected from the open world to be ‘summoned’ into their book - a neat, meaningful nod to the game’s online multiplayer.)

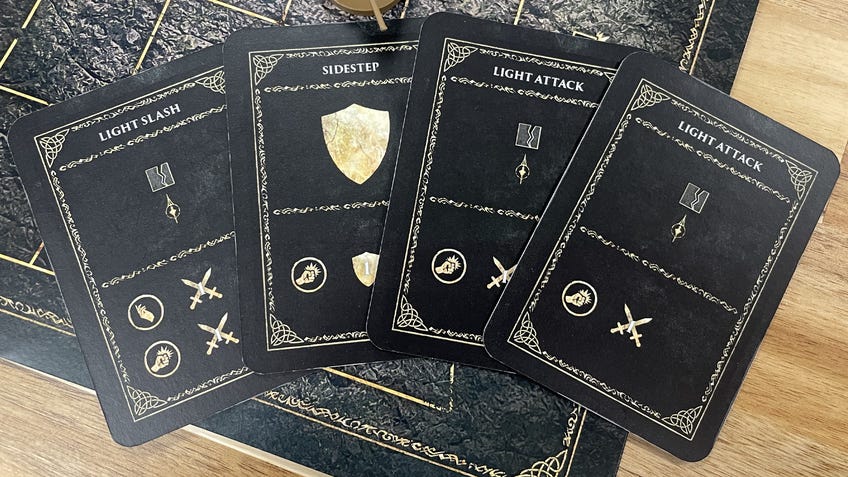

The battle grid combines with a set of attack cards that each player draws from their character’s individual deck to determine their available attack moves, blocks and evasion, three of which can be played each turn. The exact makeup of each deck is determined by a character’s equipment, with the likes of swords, bows and magic adding different cards to reflect the varying movesets of each weapon. These cards present options for various attacks - from lighter attacks that include movement to heavier moves that deal more damage but might leave the character open to a counterattack - but also represent the key resource of stamina.

In the video games, stamina must be spent wisely to avoid overexerting and being unable to dodge or block. Here, that’s represented by the limited number of cards in a player’s hand - starting with around just four, depending on the character - and the decision of whether to use them during your turn or save them to fend off enemy attacks.

The attack cards pair with an effect deck, used in place of dice to somewhat randomly calculate damage, defence and other possible effects. The deck is modified by a character’s stats - which can be upgraded over the course of Elden Ring: The Board Game’s campaign - allowing players to spec their character towards dealing damage with strength, being more likely to evade with dexterity and so on. Attack cards can also be spent facedown as generic effect cards, granting the chance to mitigate incoming damage if you find yourself in a pinch.

The board game appears to understand the spirit of Elden Ring, without being beholden to its letter.

The overall effect is admirably faithful to the feel of Elden Ring on screen, without being hamstrung by the need to remain overly faithful to the nuts-and-bolts mechanisms of its combat system. The board game appears to understand the spirit of Elden Ring, without being beholden to its letter.

In the same way, battles feel dangerous but not unfair. Swapping the dice of the Dark Souls board game for cards gives players more control over the outcome, and successfully captures the muscle memory of fights in the video game. Players can see enemies’ upcoming moves and attacks in the initiative order of cards, giving them the chance to plan around what feels like predictable but challenging cardboard AI. It’s just enough foresight to make it feel like you’re weaving between attacks and pulling off clever combos, without draining any tension out of the series famous for its ‘You Died’ difficulty.

While individual battles with smaller foes out in the open world are more a means to an end, helping to collect materials and achieve objectives (players can rest at a nearby Site of Grace to reactivate the tokens and fight them again for extra loot), the Elden Ring board game finds a way to make the climactic boss battle of each session feel another level beyond.

Once the quest’s objectives have been completed, a map tile unlocks with an icon for the quest’s dungeon. The players gather on the tile to access the final encounters, which pulls the entire group off the map and into the boss’ arena.

Like smaller fights, this plays out in the pages of the Quest Book. Except here it’s multiple Quest Books combined into a single battlefield, taking up several times the table space of a single book. It’s a fun, impressive way to make bosses feel significantly more dangerous and cinematic - as well as allowing the designers to play around with the shape and layout of dungeons once players are familiar with the basic flow of combat, Matthews says.

Bosses scale to the number of players, playing a number of attack cards to the initiative row equal to the number of humans around the table. Like the highlights of Dark Souls: The Board Game’s boss fights, these attacks can evolve and change over time as enemies take damage, replicating the distinct phases of video game boss battles and helping each mighty foe to feel close in behaviour to its on-screen counterpart.

Elden Ring's combat system is an intelligent distillation of video game timing and positioning to a square grid and cards.

In the case of our demo, the Beastman of Farum Azula took massive swipes across the arena, moving between columns as it lunged forward towards the line that divides the player’s characters and enemies on the battle grid. When it reached the dividing line (no models can cross it), the boss would reset to the back row, while forcing all the players to discard a card - a way of simulating its stamina-draining assaults.

Our party’s Samurai used their unique manoeuvrability to dodge diagonally between attacks, while the tanky Vagabond helped absorb hits and the magic-using Astrologer charged up their attacks from the back rows - demonstrating a notable change in how spell-casting classes perform attacks, as they generate Focus tokens before spending them to chain together combos of powerful spells.

A couple of Effigies were spent to bring back fallen members of the party after some especially nasty swipes, but eventually the Beastman fell - leaving our demo at an end. Matthews explained that, in the full game, the group will retire to the Roundtable Hold between adventures to pick up new quests, upgrade equipment, spend their collected runes on levelling up - adding more cards to a character’s effects deck or the ongoing bonus of trait cards - and use materials gathered from the world to craft new items and gear, which are added to the card deck to appear as loot in future sessions.

With Elden Ring: The Board Game’s first core box Realm of the Grafted King said to span 15 main scenarios - for a total of over 20 hours of mainline campaign progression - and “several” more boxes and expansions planned for the future to cover the whole of the video game’s vast world, our 90-minute demo barely scratched the surface of what’s planned for the ambitious tabletop adaptation.

Our slice of gameplay was enough to get a good feel for the board game’s unique combat system, which impressed with its intelligent distillation of video game timing and positioning to a square grid and cards. It’s a major step up from the messy execution of the original Dark Souls board game, and a rock-solid foundation for what could become an engrossing level of character customisation and encounter variety across the breadth of Elden Ring: The Board Game’s campaign.

Its exploration, by nature of its simple move-and-interact structure, so far feels like a lesser part of the game and largely a prelude to the impressive fights - but we saw very little of the game’s narrative elements beyond the tutorial’s basic objectives, leaving room for interaction with NPCs and side quests to flesh out the story of each group’s adventures. Matthews teased the presence of beloved characters such as Patches and players’ own decisions as having a lasting effect through the rest of the campaign; how large a role they play and how deep that narrative goes remains to be seen, but the signs are positive that this adaptation is being thoughtfully handled.

Elden Ring: The Board Game isn’t expected to hit tables fully until 2024, but our early look left hope that it will live up to the lofty expectations set by the video game’s absorbing combat and fascinating world. There’s a good bit of polish being applied to these Tarnished, it seems.