D&D 5E is changing – and not everyone is going to be happy

D&D 5E, meet D&D 5.5.

Is there anything more divisive in the Dungeons & Dragons community than the launch of a new ruleset? Years after the 2014 launch of D&D 5E, the most popular version of the game to date, we still can’t seem to move on from what earlier editions did better.

Online forums are full of daily musings on whether Dungeons & Dragons needs a return to some of the core features of its predecessor, Fourth Edition – more ‘at-will’ abilities for martial classes and shorter ‘short rest’ mechanics being chief among them.

Part of the fun of the D&D community is this endless, never-quite-won argument over the finer details of game mechanics, a back-and-forth (and occasionally frustrating) debate that sharpens our collective understanding of tabletop RPG design.

But it’s hard to argue with the sheer dominance of D&D 5E, the current iteration. Fifth Edition is what pulled the game ahead of its competitor Pathfinder (which enjoyed a lead during the days of 4E), created a simplified and accessible ruleset for new players, and hit big with the advent of online streaming and RPG actual play shows like Critical Role and Dimension 20.

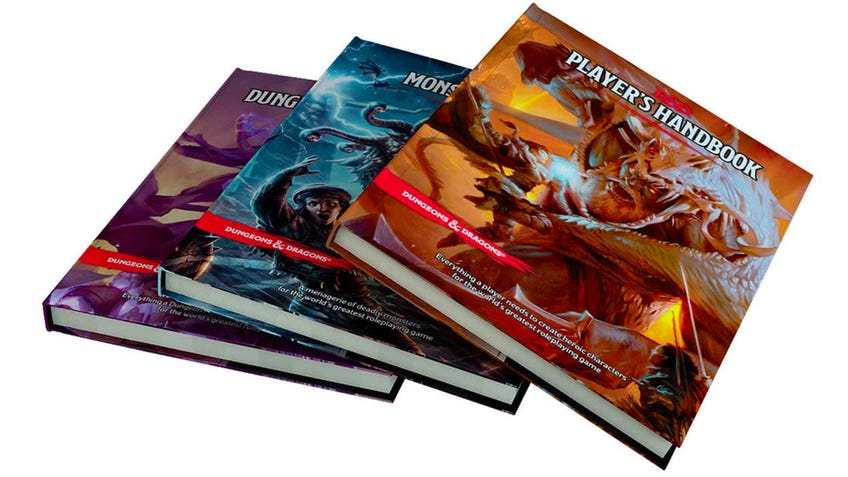

Regardless, changes are afoot. When Wizards of the Coast revealed that the three key sourcebooks (Player’s Handbook, Dungeon Master’s Guide, Monster Manual) will receive a refresh in 2024 – the 10-year anniversary of its 5E golden child, and the 50th anniversary of Dungeons & Dragons as a whole – company reps were careful not to call it a new ‘edition’, but rather an “evolution” that would be backwards-compatible with the bestselling 5E media published so far.

It’s likely we won’t see a massive overhaul of 5E’s popular ruleset – more D&D 5.5 than D&D 6E.

It’s likely we won’t see a massive overhaul of 5E’s popular ruleset, then – more D&D 5.5 than D&D 6E – and we’re already seeing smaller tweaks and changes eke out over recent sourcebooks that point the way ahead.

We’ve seen changes to racial modifiers in 2020’s Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything, allowing players to pick their own ability score increases, rather than being locked in to traditional class choices and playstyles – a high-strength orc, high-dexterity elf and the like - and helping D&D to sidestep some problematic racial tropes at the same time.

Going even further, Tasha’s customised lineage feature allows you to build up a player race from scratch, picking languages, proficiencies and even feats to assemble the character of your dreams (or nightmares).

Some are mourning changes to the ‘classic’ formula, but it certainly makes character creation more forgiving. It’s easier to follow your imagination without worrying about mechanical disadvantages, and formalises the kind of flexibility likely found at a lot of D&D tables already – as with Tasha’s optional rule to help players switch subclasses mid-campaign.

It’s likely these changes will be codified in the new primary sourcebooks, stressing narrative freedom and flavour over needless player restrictions. I’d expect small class revisions seen in Tasha’s that boost Barbarian proficiencies (to help them shine outside of combat) or the Ranger (to help them shine outside of a specific terrain) to become enshrined in the new books, too – possibly along with a revised Artificer, as the newest 5E class – with a stress on making each class feel fun and useful in any of D&D’s core pillars.

With the influence of actual-play shows, which focus so much on character development, relationships and roleplay – instead of simply loot and battle – D&D’s creators will want to ensure every class can feel like the main character in a mix of situations, and at a mix of player tables. Nothing is a bigger turn-off than playing D&D for the first time and finding your character isn’t built for the adventure you happened to land in - and more multifaceted class design helps to paper over the cracks of everyday casual play.

There has long been a shifting cycle of complexity and simplicity between D&D editions, back to the days of Advanced D&D.

We’re also seeing the arrival of feat trees, which unlock additional abilities at higher levels, and it’s likely we’ll see something of a feat overhaul in the coming reset. Feats vary hugely in their power and usefulness across all the 5E sourcebooks, and having feats that ‘start small’ and scale with character level – in the same way as any ability built on proficiency bonus – should help to smooth out progression in the game.

Not everyone will like these changes, or the intent to simplify and codify more of the game’s sprawling mechanics. Some will take issue with a game that feels increasingly streamlined, and where character classes are – quite forgivingly – better set to shine in all situations instead of particular tactical niches. Some will prefer the challenges of previous editions over the cleaner story vehicle that 5E is becoming.

But there has long been a shifting cycle of complexity and simplicity between D&D editions, back to the days of Advanced D&D (featured memorably in the recent season of Stranger Things) and the simpler Basic Set, both of which launched in the late ‘70s.

The launch of 4E in 2007 saw a new Player’s Handbook printed every year to include new and updated classes. More recently, the Unearthed Arcana website regularly teases revisions of old mechanics or new ones entirely, while lead D&D designer Jeremy Crawford corrects and explicates countless mechanical uncertainties on his Twitter account and the Sage Advice blog. Ongoing changes are simply part of the game’s DNA.

It was only in D&D’s Third Edition that the 20-sided die became such a central mechanic of the game, but the perceived complexity of that edition meant it saw a 3.5 revision only three years after release, and the arrival of 4E only four years after that (much to the chagrin of those who’d fully bought into the previous edition).

If we’re now having to wait 10 years for D&D 5E to turn into 5.5E, it seems like that oscillation is slowing down hugely – that there’s simply less to change, or fiddle with, when an edition hits its current level of success.

We may not go back to 4E, and not everyone will be happy. But a lot of people already are.