How to make a great dungeon for Dungeons & Dragons 5E

Ten tips to help turn you into a true dungeon master.

Dungeons take pride of place as the first ‘D’ of D&D, and it’s easy to see why. They condense the action into a restricted space with every choice ahead, every step into the unknown, fraught with the promise of riches or danger.

There’s a wealth of dungeons in published adventures for Dungeons & Dragons 5E, and plenty more if you draw from earlier editions and other fantasy dungeon-crawler games. But sooner or later, most DMs will get the itch to create one of their own.

To give budding dungeon designers a hand, here are 10 tips to consider when crafting a D&D dungeon your players will remember.

- Why (and where) does your dungeon exist?: Coming up with the origins of your dungeon.

- Hook ‘em in: So, your dungeon exists - but why should the players delve into it?

- How tough are we talking?: Keeping monsters and other threats just challenging enough.

- Map things out: Give your creation some physicality by putting pen to paper.

- Hide a few secrets: Ensuring your dungeon is more than meets the eye.

- Give monsters their own story: Making monster more than just sword fodder.

- With tricky traps and horrible hazards, less is more: Being sparing with your dungeon's threats can be more effective than running a gauntlet.

- Pose a few puzzles: Breaking up combat with some battles of the mind.

- Tempt with treasure that’s worth the risk: Rewarding your players for their dangerous delving.

- Bring your dungeon alive: With everything in place, it's time to ensure it's more than a static backdrop.

1. Why (and where) does your dungeon exist?

The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of your dungeon. Dungeons in D&D aren’t necessarily just underground corridors and players will appreciate some variety. As long as it has passages and rooms, almost anything can be run like a dungeon: temples, manors, natural caves, a city block, catacombs, crashed spaceships - you name it.

The ‘why’ of the dungeon comes from its history. Why was it built? Does it still serve its original purpose or has it fallen into ruin and become squatted by monsters?

The dungeon’s concept determines its aesthetic theme - the ‘dressing’ to keep in mind when you describe areas. Is it dark and gloomy, scattered with dusty relics of bygone inhabitants? Eldritch and weird, bending the laws of nature with bizarre dimensions and mutated flora abominations? A lived-in stronghold, shaped by the practical daily lives of its inhabitants?

When placing the dungeon in your campaign world, consider its effects on its wider surroundings. Monster incursions, environmental corruption, local rumours and legends can all be fuel for hooks.

2. Hook ‘em in

Dungeons tend to be nasty places that most people would avoid. Even adventurers should have a motivation for risking their lives in one. Some of the best story hooks don’t just rely on moving a plot along but also tantalise players with something that they really want.

Power-hungry players could be drawn to rumours of mighty magical weapons or spells lost in the depths. Eager roleplayers can be hooked by a family connection to the dungeon, or their organisation’s interest in it. A favoured NPC could fall victim to a disease, with the only cure being a draught from the enchanted fountain of the lost city. A villain escapes an encounter and retreats to the dungeon, preparing for vengeance.

Whenever you can, make it personal. You can also dangle several hooks for different players. (Some) inter-party conflict on the priorities of an expedition can lead to fun roleplaying moments.

3. How tough are we talking?

Before putting the dungeon down on paper, spare a thought for the poor player characters who will be subjected to its terrors. You should have a certain level range in mind when designing the dungeon and calibrate the challenge accordingly.

The challenge ratings for encounters given in the D&D 5E Dungeon Master’s Guide are a good baseline to work from, but you don’t need to perfectly balance every encounter to PC level. Some encounters can be ‘speed bumps’ there to drain resources, but the most memorable ones are those in which players feel like they’ve overcome a real threat.

‘Deadly’ encounters should guard the best rewards, but don’t force players into a hopeless fight. Trickery, negotiation, allying with NPCs or retreat should always be an option.

Something that beginner DMs can often overlook is the effects of attrition, especially in longer dungeon crawls. A dungeon adventure in which players can afford to take a long rest, buy items and replenish their resources plays very differently from one where they can’t.

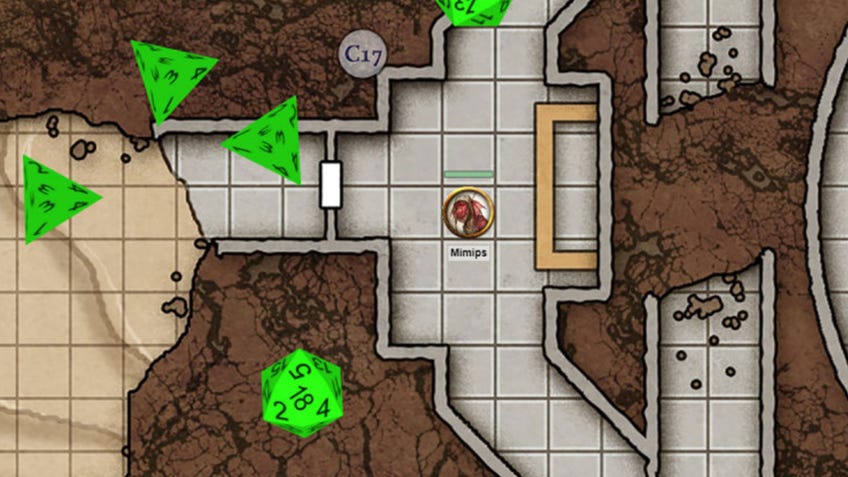

4. Map things out

Now’s the time to bust out the graph paper and unleash your inner architect. Size matters here. How many levels? How many rooms? Consider room dimensions, entrances and exits, and so on.

Big, sprawling mega-dungeons can be the focus of entire D&D campaigns, but when designing your first bespoke dungeon, it pays to start small. A one-page dungeon of five rooms with three monster encounters, a trap, a hazard and a puzzle or secret makes a good one-shot adventure location for a couple of hours of play.

For bigger dungeons, think vertically as well as horizontally. Multi-level dungeons should have several ways to go up or down. Shafts, chutes, elevators and teleporters can provide alternate routes to simple stairs, and can ‘skip’ some levels for a shortcut. Revisit your concept - each level should have a different flavour to the others.

If you’re stuck planning a larger dungeon, use the D&D 5E Dungeon Master’s Guide’s random tables (or the various online tools) and adjust the parts that you don’t like. Looking at a random map and ‘fixing’ what doesn’t look right will give you an idea of the logic you want in your own creation.

5. Hide a few secrets

Every dungeon should have something that’s more than meets the eye. It can be difficult to make ‘missable’ content, but it does make exploration more rewarding. A secret should be something interesting that requires some effort to discover.

This can be the typical secret door leading to a hidden area or something else that isn’t what it seems - an illusion that makes treasure look like junk, or a shapechanged monster.

Scatter hints in the form of written clues, maps or diagrams that can hook players into looking for the secret. A monster could also offer a clue as part of negotiations. Secrets should be mostly beneficial but occasionally unleash a terrible consequence. Some are best left buried, after all...

6. Give monsters their own story

Now that you’ve planned out your dungeon, it’s time to populate it. Monsters should fit your concept but have their own reasons to dwell there. Consider how monsters relate to each other. Do the troglodytes fear the nearby carrion crawlers? Or have they ‘tamed’ them through offerings of food?

Groups of intelligent humanoids will have areas for sleeping, storage, headquarters, shrines, labs and so on. Large beasts will have their lair but also hunt near more vulnerable creatures.

Group your monsters into two or more factions with conflicting goals. Perhaps they’re fighting for control of a resource or artefact, or territory. Even in small dungeons with only one monster type, there can be rivalries. Maybe the orc champion is plotting against the chieftain and cultivates their own following in secret.

Player character actions disrupt the balance of power between factions and change up dungeon politics. Smart players who notice what’s going on will see a great roleplaying opportunity to strike alliances - or divide and conquer.

7. With tricky traps and horrible hazards, less is more

Unless being a gauntlet of traps is the dungeon’s concept, try not to overdo these - the denizens will hardly appreciate having to disarm five separate traps on their way to the latrine and back.

The D&D 5E Dungeon Master’s Guide lists the greatest hits of traps and hazards (pits, poison needles, green slime, etc.) and has tables for traps by damage type. But don’t limit your imagination to hit point damage. For memorable traps, try to design some that put the victims in a difficult situation.

A trap that immobilises characters via adhesive or magic, for example, and sounds an alarm to alert monsters, creates a more interesting scenario than knocking off hit points. Monsters should work in tandem with traps; it’s their home turf advantage.

8. Pose a few puzzles

Puzzles are a great way to break up the usual D&D rhythm of attack rolls and ability checks and get the players thinking outside the box. Try to avoid relying on game mechanics as a solution to puzzles; instead, let players solve them via lateral thinking and some trial and error.

Most puzzles rely on pattern recognition and should be something that players can figure out using general knowledge or your game world’s lore. It can be specific to D&D - "These symbols represent the nine alignments! But shouldn’t law and chaos be opposite each other?" - or to the dungeon itself.

Puzzles can be combined with traps for additional hilarity or with secrets to make them harder to find.

9. Tempt with treasure that’s worth the risk

Minor treasure can be liberally sprinkled around a dungeon to keep players on the lookout for more. The really good stuff should be hard to get - a reward for overcoming a challenging encounter, trap, puzzle or secret. Place your choice prizes accordingly.

If you want your dungeon to be memorable, include a unique magic item of your own design, tied to the history of the dungeon. Several iconic D&D items, like the soul-sucking sword Blackrazor, were introduced in specific dungeons.

10. Bring your dungeon alive

When you have your dungeon planned, it’s time to think about how it comes alive. Monsters won’t necessarily sit twiddling their thumbs (or tentacles, claws or what have you) in the face of the carnage that typically comes with an incursion of adventurers. Try to anticipate the party’s likely routes through the dungeon and plan appropriate reactions from the inhabitants.

Your players will inevitably surprise you, but monster activity such as shoring up defenses, securing treasure, setting new traps or actively hunting invaders will make them think twice before taking their short rests for granted. A lot can happen in one hour, and it always adds a little tension when adventurers notice that a room isn’t quite the same as they left it.