Playing Diplomacy online transformed the infamously brutal board game from unbearable to brilliant

Another backstab at it.

Diplomacy is a 61-year-old board game about taking over Europe. It’s a true classic - highly influential, intensely beloved and widely acclaimed - and the first time I played it, I thought it was rubbish.

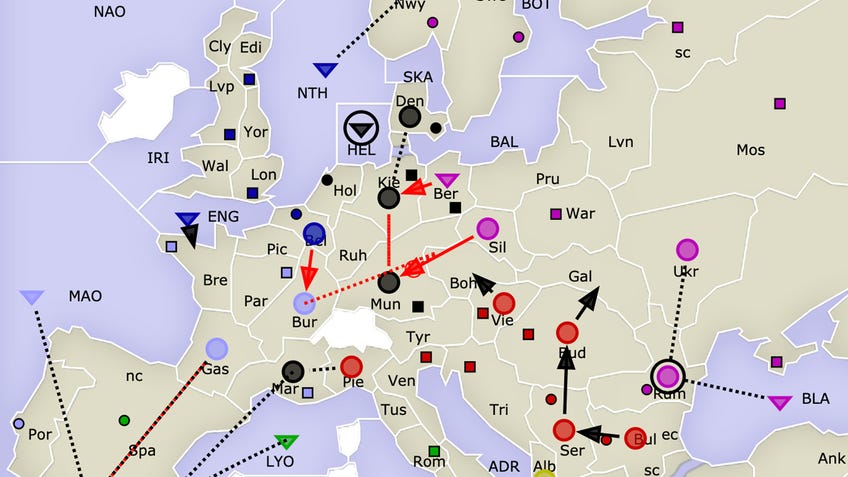

In Diplomacy, each player controls one of seven nations at the start of the 20th century, submitting movement orders to their armies and fleets each turn in order to gain new territories and thereby build more troops - the goal being to control 18 of the game’s supply cities at the same time. Its rules are simple enough to make Risk look fiendishly difficult and yet, all the same, it is an extremely nuanced game of strategy and cunning. (JFK apparently enjoyed the game, as did Henry Kissinger.)

This is because the beating heart of Diplomacy is in the alliances and agreements players make in-between submitting orders. It is a game conducted not on the board, but in whispered conversations and secret messages. No arrangement made in a game of Diplomacy is binding, encouraging players to lie to and betray one another at will. As such, it’s earned an infamous reputation as a way to ruin friendships over the course of an evening.

It is simple, it is stunning and, like I said, I thought it was pants.

Without spinning you a long tale of who said what as some friends and I nattered, bickered and drank endless cups of tea one spring afternoon several years ago, I had a rubbish time in my first game of Diplomacy. I was sandwiched between two cagey and competitive players who weren’t overly interested in talking to me or making any agreements. On reflection, I think they’d agreed to simply wipe me out in a pincer movement from the start - because that’s exactly what happened. I was squeezed out of the game in short order and left wondering what all the fuss was about.

Diplomacy is a game conducted not on the board, but in whispered conversations and secret messages.

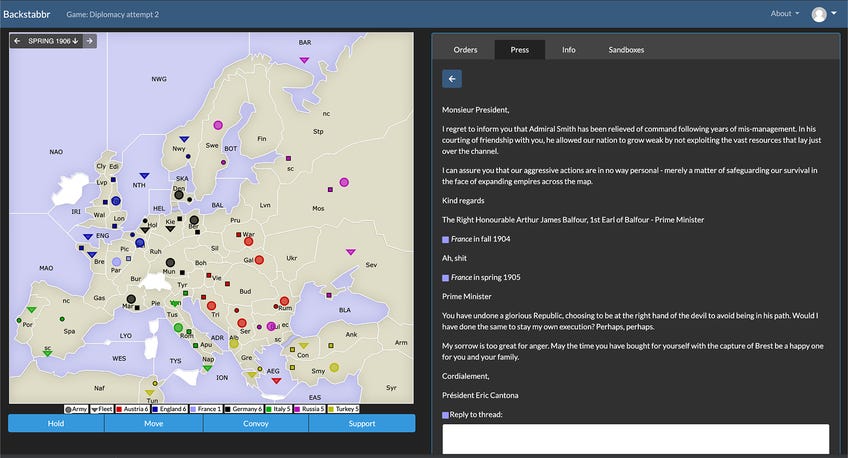

Fast-forward to a few weeks ago, when a friend invited me to play a game of Diplomacy on a website called Backstabbr. I accepted, thinking it might be a fun way to pass the time during isolation. Little did I suspect that it would transform Diplomacy in my eyes and cement it as one of my absolute favourite board games.

Essentially, Backstabbr simulates a Diplomacy match played by post. In the game I am currently a part of, we resolve one set of orders (i.e. one round of troop movement) per day. Negotiation is done by sending messages via Backstabbr’s inbox or ‘press’ functionality, meaning a phase that might take ten minutes in a normal game of Diplomacy now lasts 24 hours. Needless to say, we are writing a lot of letters.

Repeatedly stretching one phase of a board game until it lasts a full day sounds, I freely admit, like a terrible idea. It’s that extra time, however - along with saying things in text rather than in person - that has completely transformed the experience of playing Diplomacy for me.

For one thing, it’s infinitely more nuanced. Playing in person, it’s very hard to talk to one player, then another, then return to the original player and continue an earlier conversation. Even if the discussion is relatively innocuous, it’s not a good look - someone is going to suspect you’re getting ready for a whopping betrayal. Finding the space to conduct a secret conversation can also be hard when, like me, you live in a pokey flat, meaning these discussions can be both rushed and brusque.

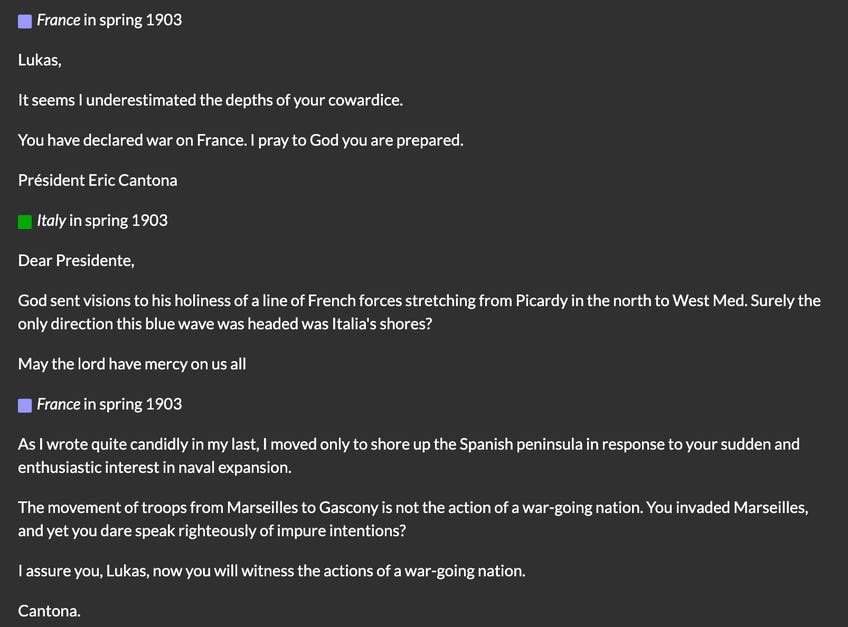

By writing letters to one another over a longer period of time, you have a far greater range of options. You might choose to keep an open dialogue with other nations, keeping them informed (or woefully misinformed, as the case may be) as best suits your purpose. You might hastily seal a cunning alliance at the very last moment while no-one else is the wiser. Or, my favourite, you might leave someone waiting on your reply for a couple of hours, letting them sweat it out until they’re more willing to negotiate. Additionally, you can choose your words more carefully by post than in person, opening up a wealth of thinly-veiled threats, hints, suggestions and insults that I am not witty enough to deploy in an actual conversation.

The extra time, along with saying things in text rather than in person, has completely transformed the experience of playing Diplomacy for me.

These greater tactical options are enriching in and of themselves, but it also helps that playing over the internet is considerably less stressful than playing in person, something I can find to be absolutely exhausting. I love my friends dearly, so lying to their faces in a social setting is a tiring task for any length of time, let alone an entire afternoon. Given the sincerity that needs to be put into some persuasion efforts, it’s no wonder some people get genuinely upset when their closest friend and ally stabs them in the back - it feels like a real betrayal because that’s exactly what it is. While playing by post exponentially increases the amount of time you’re lying to your friends for, these are lies doled out in short bursts rather than one sustained effort, allowing players to differentiate between being ‘on’ and not. I played a game of Dungeons & Dragons with my Diplomacy friends over the weekend and I didn’t think about the lies I’d been telling them at all. Well, not much, anyway.

Given how stressful playing in person can be, very few players choose to roleplay as their chosen faction, instead simply playing as themselves - and therefore putting themselves out there, which is dangerous in a game of Diplomacy. That’s no surprise, of course - frankly, there’s enough going on without also having to open every single conversation with ‘Hail and well met, dear Kaiser’ or something similar.

Not so by post, my oldest and dearest ally! I have spent the last three weeks writing flowery missives as Présient Eric Cantona, the tough-talking and often enigmatic French Premier. At one point I replied to a letter needling me for information with the footballer’s famous “When the seagulls follow the trawler” quote and it genuinely helped things along. Along similar lines, my friend Dean, originally from Dublin, was dismayed to find himself playing as the Brits, so simply sent everyone a letter from the new High King of ‘Big Ireland’, announcing that the Irish war for Independence had gone very, very well indeed.

While there’s plenty of room for silliness, some of these exchanges have also been genuinely electrifying, and all the more so for having characters thrown into the mix - however thin they may be. By the same token, putting on a character to write letters has helped take some of the sting out of what is, at its core, an absolutely brutal board game.

While there’s plenty of room for silliness, some of these exchanges have also been genuinely electrifying.

At the time of writing, Président Cantona’s France is about to be wiped out. The other day, I woke up to a joint assault from Italy and from Germany, my supposed ally. While I was pleased to have seen the betrayal coming, I was genuinely quite sad. That sadness, however, was more akin to the feeling of losing a beloved RPG character than an actual, real-life betrayal - I was sad that my part in the narrative and all the fun of roleplaying as this alternate-history French Republic was certain to end soon. As genuine as those emotions were, I was still having video calls with my traitor friends and enjoying a giggle that same day. I am almost certain I’d have been more hurt had we been in someone’s living room.

That’s not to say playing Diplomacy by post is for everyone. It is still a very involved, stressful experience; one that’s cost me no small amount of sleep over the last few weeks. All the same, it’s been an exhilarating ride - I’m not sure how many other board games from 60 years ago that can be said for.