The best adventure board game you've never heard of turns translating medieval manuscripts into a compelling odyssey

Paint a Vulgari picture.

I prejudge a new board game by a simple maxim: the beige-er, the better. Spare me your pastels, your bright splashes of colour - I demand beige, ochre, taupe, chestnut.

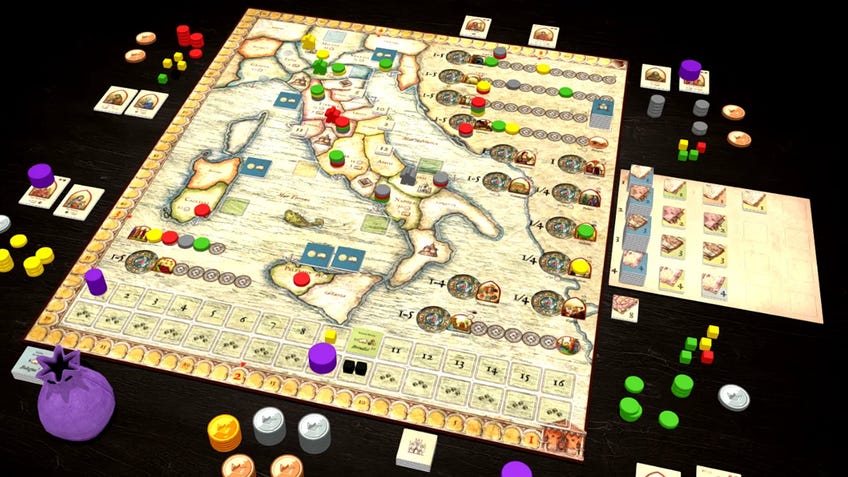

By this metric, De Vulgari Eloquentia is already a winner in my eyes, featuring some of the beigiest beige this side of faded illuminated manuscript. But, in a medium chock-full of tan-colored games featuring grim merchants counting coins, it likely passed many by when it was first published in 2010. A shame, because this is one of the greatest adventure games ever made, breathing incredible life and personality into its sienna-toned cardboard.

The premise of the game is - wait for it - language. Well, language-making. Everyone starts as a humble merchant. Your mission? Create the Vulgari, which is a historical ancestor of modern Italian. You’re going to do this by wandering around a map, doing trades for cash (presumably speaking this new language), hobnobbing with monks, abbots and nuns, and digging up and translating manuscripts.

How do you do this? With tracks. Lots of tracks.

De Vulgari Eloquentia somehow manages to take some of the driest mechanisms in board gaming and make them feel like a high-octane experience. Rather than getting too into the weeds explaining how everything works, it’s easier to understand the game as a medieval life simulator. Everything is expensive. From the first move of the game, you attempt to play out the life story of your little character. Here’s one example.

De Vulgari Eloquentia somehow manages to take some of the driest mechanisms in board gaming and make them feel like a high-octane experience.

I begin in Cagliari, a small island region in the western part of Italy. My entire little medieval Italian life, I’ve wanted to be a monk, devoting myself to scholarly enterprises. I sail across the ocean to land in Genova, before snaking my way down the boot, befriending abbesses, recruiting politicians and eventually arriving at a convent, where I give away half of my wealth to don the robes of a friar. I continue my journey, eventually rising to the rank of cardinal, and I alone discover the secret Riddle of Verona.

That’s one of hundreds of possible stories the game contains. But, for the mechanically inclined, the game utilises an action-point system, where you spend points to move around, collect manuscript tiles, buy cubes and then exchange said cubes to move up various tracks for endgame score.

The game is entirely deterministic, meaning there is no hidden information or random surprises. You can keep the money and cubes you collect secret, but it doesn’t matter much. An event system, which serves as the game clock, splats out tiles that you race to collect each round until the pope dies, at which point everyone gets to participate in a one-time auction for more money and points.

De Vulgari Eloquentia embraces the theme of adventure and discovery wholeheartedly.

I mentioned in my story above that you can become a friar, which is a lovely mechanic where you can decide to give up half your money in exchange for a power and slightly different scoring conditions at the end of the game. If you keep going down this path, you become a cardinal. Plus, the richest merchant player has to pay money to all the cardinals and friars every round, adding an interesting point of interaction. You can win in any of the three roles, and it’s always a hoot to compete with the other cardinals to become pope at the end of the game.

‘Theme’ is a term that’s bandied about quite a bit in gaming circles, but I often find people using ‘theme’ in place of the word ‘setting’, or ‘appearance’. De Vulgari Eloquentia embraces the theme of adventure and discovery wholeheartedly. You decide to seek your fortune in its small cardboard world, racing against time and the other players in your quest. The game captures the difficulty and expense of movement in the Middle Ages, the challenge of dragging literacy away from the elite classes, and the importance of patronage networks.

The game received a “deluxe” re-release in 2019, and is still (I think) available from publisher Giochix and other outlets. The designer, Mario Papini, hasn’t had much commercial success as far as I can tell, in spite of putting out some incredibly unique designs: Feudo, an area-control game where you also give people the plague; Siena, an auction game about being a peasant; and Lancelot, a race game where you’re one of King Arthur’s knights. Mario Papini - making Pentiment before it was cool.

When people talk about immersion, I think they’re actually talking about logic. In order for something to feel real, immersive, compelling, it has to have a clear and concrete logic justifying the things you’re doing. The beauty of tabletop games is that players collectively decide how potent that logic is, and bring it to life together. I’ve yet to have a play of De Vulgari Eloquentia that doesn’t feature someone grinning as they advance within the church or brashly try to win as a merchant, building a hill of gold.

De Vulgari Eloquentia is a love letter to games as canvases upon which we paint ourselves, and I can’t find higher praise for a design than that.