Asymmetric board game Crescent Moon isn’t quite the next Root, but fans (and everybody else) should still play it

Among the stars.

At first blush, Crescent Moon is easy to compare to Root. While Cole Wehrle’s masterpiece of warring woodland creatures looms large over this new asymmetrical board game, it’s by no means eclipsed - and what emerges from behind that sizeable shadow shines very brightly.

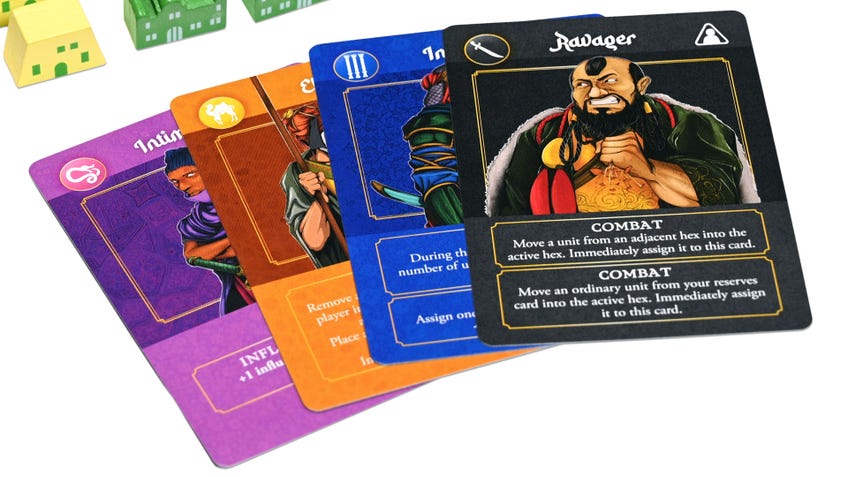

Like Root, Crescent Moon offers each of its four or five players a different set of rules and objectives that they must use to seize control of a board broken into distinct regions. Like Root, that means that multiple plays - each lasting at least a couple of solid hours - will be needed to fully wrap your head around how all of Crescent Moon’s factions interlock and collide, and you’ll want a full table of players for the intended experience. Like Root, Crescent Moon is a game where the competition leaps off of the table into discussions between players as they form uneasy alliances and agreements to stop a runaway winner, before burning all their bridges in their own push for victory. And like Root, Crescent Moon is an absolute stunner on the table thanks to its combination of vivid, stylised artwork across its hex tiles, cards and wooden pieces representing towns, forts and the Caliph’s palace.

Yet, assuming Crescent Moon is little more than a simple attempt to relocate the animal allegory of Root to the human realm of a 10th-century Middle East would be doing it a major disservice. (The game’s rulebook cites input from a cultural and historical consultant and the Muslim background of artist Navid Rahman on its abstracted depiction of real-world history.) While it shares some similarities with Root’s asymmetrical gameplay and clever blend of fanged aggression and gritted-teeth collaboration, Crescent Moon is a different game - sometimes better, sometimes lesser and sometimes, well, just different.

The game takes place in a region of the Middle East; a number of possible maps can be formed by its modular map tiles, providing a shifting landscape of rivers, quarries, a holy site and fertile ground centred around a river crossing. The rulebook provides suggested setups, while more advanced players can create the map themselves before play.

The land is occupied by a ruling Caliph, combative Warlord, influential Murshid, wealthy Sultan and opportunistic Nomad. Each is looking to seek power in their own way - through baldfaced aggression, subtler subterfuge or exploiting the needs of the others - which provide the sizzling coal inside Crescent Moon’s hardworking strategic and social engine.

Like many of the greatest board games of all time - designer Steven Mathers has cited perennial classic Dune and Eric Lang’s beloved Warhammer game Chaos in the Old World as key influences - Crescent Moon’s best moments are driven by the necessary interactions between players.

Money and military might both balance on the precarious links between each faction. Players must rely on each other to have any chance of expanding their influence and control over the land and pursuing their own ends. Each player scores points in unique ways at the end of each round - representing one year in the game’s universe - with an additional bonus only available during the first year, smartly pointing players in a suitable starting direction. Each faction’s reference booklet provides clear guidance on their possible actions and unique abilities, alongside helpful advice on how to lean into their distinctive strategies.

Crescent Moon excels at imbuing seemingly simple actions with the potential for dramatic stakes, weaving an engrossing narrative into the way that players are forced to benefit those with whom they’re opposed.

While it shares some similarities with Root, Crescent Moon is a different game - sometimes better, sometimes lesser and sometimes, well, just different.

Take the example of the Nomad, Crescent Moon’s weapons dealer who thrives on supplying others with their means of conquest. Several of the players must strike a deal with the roving band of mercs to wield any military power, but the Nomad player can use their own turn to disband units, resulting in the need to keep them somewhat friendly - or at least unaware - or risk seeing your army suddenly switch sides at a crucial moment. It’s deliciously fraught with will they-won’t they betrayal.

Meanwhile, players can haggle with the cash-flush Sultan over the price of helpful power cards on their dedicated market board - a potentially cheaper alternative to the fixed cost of cards in the rest of the market, but only if you can keep the Sultan on-side. A difficult task when their towns and cities offer such bountiful wealth to be claimed through sacking - especially by the building-averse Warlord, who can only seize others’ settlements and strongholds for their own and excels in sparking conflict across the map.

In another particularly devious detail, the influence-exerting Murshid can use the sway of their influence tokens - which can coexist alongside another player’s military control of a space, signifying the separate rule by iron fist or hearts and minds - to offer support to another player fighting in a nearby region in exchange for a number of victory points. If the warring player wins, the Murshid gains the points - whether or not they did actually throw in with the side, encouraging them to help without guaranteeing that they will follow through on the promise.

Moments like this set the stage for a game that constantly shifts the relationship between players in a way that feels natural rather than forced or jarring, setting up alliances and betrayals that are meaningful turn to turn but won’t leave players feeling isolated or picked-on.

Importantly, interactions between players are left loose but vital enough to encourage a constant thread of diplomacy even as those same players wrestle over valuable spots on the map, hoping to hold onto them to score points and gain income at the turn of each year.

While the players’ objectives and actions differ on the surface, most connect to a shared pool of similar concepts underneath, making the board game surprisingly easy to pick up even on the first go around. Choices mostly boil down to reinforcing your army by placing tokens, seizing regions through battles of strength or influence, constructing buildings, or buying power cards, which can be used to help win fights or for other effects. Each faction augments each of these with enough potency to make each seat at the table feel satisfyingly distinct, but there’s enough of a universal structure to avoid getting bogged down in minutiae. The ease and pace of play is helped by Crescent Moon’s short turns, with each player only taking a single action in a sequence repeated four times each round - keeping things pacey and easy to follow in the moment, and allowing players to react more quickly to their opponents’ moves.

You get the sense that this is a game designed for exactly five players, awkwardly stretched to four to give its gorgeous box a little more shelf appeal.

The game’s player count of four or five is demanding, but honest; in play, you get the sense that this is a game designed for exactly five players, awkwardly stretched to four to try and give its gorgeous box a little more shelf appeal. (On the other hand, the estimated three-hour play time feels slightly inflated for a standard game - it moves at a good clip.) Losing the Nomad in a four-player game - players instead pay the central bank a fixed rate for mercenaries, and don’t risk them deserting - sacrifices one of Crescent Moon’s most intriguing parts, leaving its carefully balanced construction feeling slightly wobbly.

Having the Nomad replaced by a faceless bank seems a minor change, but it’s in the details that Crescent Moon shines brightest. It’s a game of small specifics that gently nudge players towards competition and cooperation through a mix of conflicting and harmonious abilities without stifling the opportunity for memorable stories around the table.

While it will inevitably draw comparisons to Root, Crescent Moon manages to escape its shadow to stand alone as a fascinating and engrossing board game in its own right. From my fairly short time with it so far, it’s not quite an instant classic in the same way, but it’s well worth your time whether you’re looking for a Root alternative or not.

For Root fans, it’ll scratch much of the same itch while providing a breath of fresh air and some fascinating new ideas. For newcomers, it’s a more forgiving and approachable introduction to the idea of a board game where everyone is playing their own game, but together. Given time, there’s a good chance Crescent Moon’s setting, gameplay and ideas may well cast their own long shadow.

Crescent Moon will be released on May 26th by Osprey Games.