“We're not trying to make fun games. We're trying to make good games”: Root, Pax Pamir and Oath designer Cole Wehrle argues on (and off) the tabletop

And talks joining forces with his brother Drew for Wehrlegig Games.

Cole Wehrle feels like the tabletop designer of the moment.

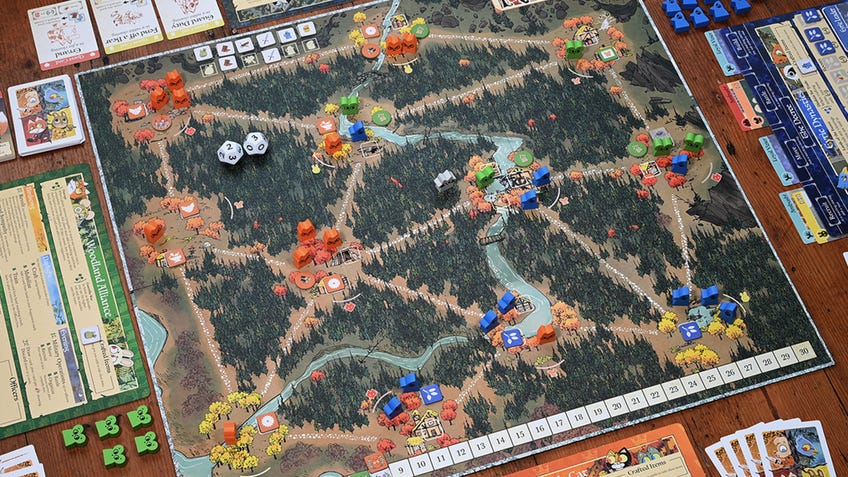

Still riding high on the acclaim that followed the release of his breakthrough board game Root in 2018, the designer joined forces with his brother, Drew, for a revised edition of his debut release, historical strategy game Pax Pamir, last year under the banner of their newly co-founded label Wehrlegig Games. (In fact, Pax Pamir: Second Edition was my favourite game of 2019.)

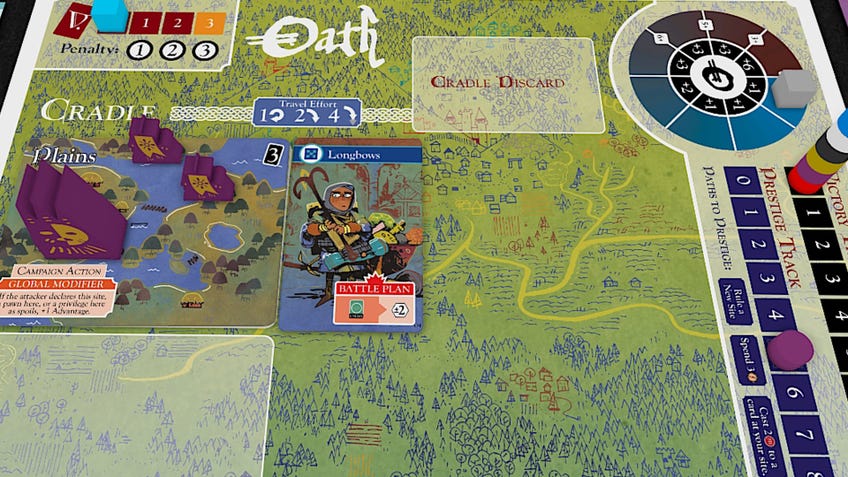

Earlier this year, Cole’s next project as part of his role as developer at Root maker Leder Games launched on Kickstarter. Due out in 2021, Oath: Chronicles of Empire & Exile is perhaps the designer’s most ambitious game yet, a game that portrays the rise and fall of a kingdom on the whim of players’ decisions. Most impressively, the game is a sort of living memory, with players’ actions in past games influencing the setup of the game and state of the world in future playthroughs. It’s not quite a legacy game, but something altogether different.

At last year’s PAX Unplugged, I sat down with Cole and Drew to talk about Oath, the siblings’ lifelong love of games, their work together and making arguments through play.

Oath is your first Leder game since Root, but it’s a very kind of different game to both that and last year’s Pax Pamir...

Cole Wehrle: The way we try to do creative projects at Leder is if you have an idea, it's very easy to ask for a little time each week. Then as your idea grows and will demand more of your own resources and the resources of the people around you, you have to make sure that, in my case, Patrick [Leder, Leder Games CEO] still thinks it's a good idea. And also I convinced the marketing staff that this would be an interesting project and you know, the production staff that we could actually make it and Kyle [Ferrin, artist on Root and Oath] that it's a place that he wants to spend a lot of time drawing.

I said, "We could work really hard for six months and throw it all away because it may not work." And for the longest time that seemed to be what was going to happen.

I got Oath to the point where I could pitch it while we were working on Root. This is early 2018. I told Patrick, "I want to build a game that has a memory, a game where the persistent character is the game itself instead of the players. But I have no idea if it's possible or it's going to work." I was like, "Before we get any further with this project, you need to accept the fact that like we could work really hard for six months and throw it all away because it may not work." And for the longest time on Oath that seemed to be what was going to happen. We're basically on version 10 or 11 - and these were like pretty fully-featured games that were being kicked to the bin - but it just wasn't quite measuring up to what I wanted the game to be. And then, right about the time my third kid was born, I went and did a long development arc. And then it was clear that afterwards there was something that was sticking. And we've been building on that.

Was Oath a deliberate result of wanting to do something mechanically very different from Root, coming out of that game?

Cole: Root looms in funny ways. Somebody asked me, "Does Root make it harder to work on the next game?" And it doesn't that much. I mean, [Pax] Pamir 2 was done after Root.

The origin of Oath was thinking about the way I wanted people to think and talk about the game when they weren't playing it.

Root very much is what it is, and there are things that allowed it to do as well as it did. But by the time I was done with Root, I had this big list of things that I couldn't work on while I was working on Root. Part of what Oath was was vetting all the stuff that had been generated while I was working on Root. It is mechanically different but also it's just about something different, so it looks different. I never had a thought of like, "Okay, so Root was good, so we're going to start with Root as the chassis and then kind of build it out." It's just not really how I work.

The origin of Oath was thinking about the way I wanted people to think and talk about the game when they weren't playing it and then sort of dialling that to the feelings that they were going to have when they were playing the game and then thinking about their interactions and the system and building up the mechanisms. By the time you follow and trace that you get something that is very different from anything else that I've worked on.

Drew, you contributed to the playtesting of Cole's past games, including Root, and more deeply in the revision of Pax Pamir 2E. Were you involved in Oath to the same degree, or has your relationship and involvement with Cole's designs changed as the result of founding Wehrlegig?

Drew Wehrle: Mostly in an informal capacity, but persistently informal, I've always been a voice for Cole to approach and kind of bounce ideas off of.

Cole: I'm very lucky to have Drew, but also a group of friends that has always very tightly orbited whatever I've been working on. Around the time that Oath started really taking shape at the end of July [2019], maybe at the beginning of August, a good friend, Chaz Threlkeld, who was the developer on [Cole’s 2017 game] John Company, came and visited. And Drew came and visited and we talked and worked on Oath just as the thing that we were doing together. And those conversations were part of the thing that sparked the actual design.

A lot of Oath has been inspired by conversations in car rides.

It's funny, someone asked me, "Oh, what single game do you think has been the most influential on Oath?" And I was like, "Oh, [Reiner] Knizia's Medici." Which is a crazy thing to say. But also that was the game that we were working together and then playing in the evenings. When we were playing Medici, I was like, "Oh, there's a formal thing that happens in Medici that I'm very interested in." And that actually kind of fixed a problem I was having with some of the Oath drafts. And at that moment, the game started clicking together in really useful ways even though there were no auctions, there's no Renaissance merchants.

Drew: A lot of Oath has been inspired by conversations in car rides and the time spent around Origins [Game Fair].

Cole: Drew and I have gone on lots of long road trips together and we always have like a road trip project where we'll be like, "Okay, we got 12 hours together, we're going to game jam," as we are driving around. We've now designed a few games.

We both come to life talking about games. I like to play games, but our conversations about a game might be longer than the playing of the game itself.

Before I got hired at Leder at Origins 2017, I was working on a deduction game about history. I did not know if it was possible, but I was like, "Okay, the idea is some awful event happened and like this great kingdom was ruined. And then you're playing historians 500 years in the future trying to figure out what happened. But then also you're publishing your books and you're trying to protect your theories and push off with your scholars and all that." So it was a game about academia. And Drew and I had this drive to Origins. Maybe three-and-a-half hours or so. And I was like, "Okay, I don't know if this game would work, let's talk about it." I remember very distinctly that conversation because [Drew] knew, "Oh, this game can't work. Like, actually it fundamentally won't work and there are all these very basic problems. It would make an okay video game. It just can't work in analogue." If I'm stuck in a project, I will see when Drew and I have the next excuse to travel somewhere.

Drew: That directly speaks to our relationship as brothers because it has provided just ample time that hasn't been allocated for specific design conversations with these design goals, but instead has been bookended by travelling and family gatherings or family visits. And that has allowed these conversations to kind of bubble up when there's been inspiration or interest around certain things, like playing Medici or whatever it's been.

Cole: We both come to life talking about games more than playing games. I like to play games, but our conversations about a game might be longer than the playing of the game itself. [We have] a real love for just getting into the weeds of how things work. Kind of like an engineer's mentality. Neither of us are engineers, but we love the puzzle of the game. So we play with our siblings a lot of competitive video games, and I relish the post-game discussion were we try to figure out: why did he lose? What happened? Really get into that element.

Playing the game is incidental. It's like, you have to do that to provide grist for the mill of analysis. And I think that heavily informs the designs.

Have you found that the games you're working on together as part of your own publisher, Wehrlegig, have changed as the result of the games you've worked on together outside of the studio?

Drew: For what I imagine, Wehrlegig's future is not just harnessing Cole and I's working dynamic and family dynamic, but utilising it and sharing the process with the public. Because these projects are unique and of themselves in terms of the kind of design decision space that we present, but also how the games have even come about. The thing that I think sets us apart is our design process does not involve the typical timeline. And it does not involve the typical formal structure that a lot of other publishing companies use because conversation is built into the core of how we deal with these topics.

Cole: One thing that will be borne out a little bit, especially over the next few years, is I think Drew's role in the games I've worked on has always been critical, but peripheral.

These projects are unique in terms of the kind of design decision space that we present, but also how the games have even come about.

Now we're in a place where you, I feel like, especially with the Reconstruction game [an unannounced Wehrlegig release set during the aftermath of the US Civil War], but even with Pamir. When we were doing the credits for Pamir, it was obvious Drew should get a developer credit because he was just there at the beginning of the project. I pitched and then you [Drew] counter-pitched; we created an idea for what it was going to be and then we executed that design. I wouldn't be surprised if we find that like, "Oh no, actually the best way to express this is a co-design credit," or whatever. We're getting to a point where, because you're getting more involved in the earlier parts of the project, you'll then start to take some of those positions.

You've previously mentioned you take a top-down approach to creating games, where you start with an argument you want to explore and then the mechanics follow on from that argument. Have you ever found yourself just trying to flip it and approach it from a mechanical side first?

Cole: Every once in a while I will have a cute mechanism and it just never [works]. It's so funny. Oath used to have an action-selection mechanism that I really like. It's very clever. It almost worked. But then about halfway through development I was like, "I think I have to throw it away."

Whenever I have tried to lead with the mechanism it always falls flat. There are a couple of weird exceptions. Usually games I make, I find that I'm making two levels of arguments. One of them is the stuff like the arguments in Pamir; those kind of ideological political arguments that are being made with that product. So those are always there.

In games I make, I find that I'm making two levels of arguments.

Then there's also mechanical arguments. Because I try really hard to play all the new stuff. And I have opinions, like capital-O Opinions, about the state of design, where people are designing, where I think modern design is not doing well and where it's doing really well. And so I try in all my games to have a mechanical argument, as well, that I'm making about the state of the hobby, about where I think games are and where they should go.

So I do think about mechanics a lot, but I just never take them as a starting point because I just find that I can build a cute little engine, but it always produces kind of a lukewarm game. Whenever I start falling in love with a mechanism, I usually force myself to kick it out because I know that it's just going to be a blind spot.

It's clear from the way Cole’s designs come together with the input of Drew and the way you work together that you're both very much on the same wavelength. Is there anything you vehemently disagree about? That as brothers working together as Wehrlegig you won't touch because you can't make it work between you?

Drew: Any friction that ever might come up regarding design decisions, or from mechanics to aesthetics all the way to how we've structured the company, we fall on the same page so often.

Cole: I mean, you [Drew] and I don't really- Okay, so we argue a lot. We don't argue; we discuss. [chuckles]

Drew and I don't argue; we discuss.

Something that never gets talked about: there is a mode if you talk to a lot of the major designers out there, or if you go to game cons, of loving all games. It's a very broad thing. And I like most games, but there's a question about taste, which is something that doesn't really get talked about too much in board gaming. Especially when you're in the industry, because you want to love everyone's work and you want to support all your friends who you've made in the industry. But I think Drew and I have very similar tastes when it comes to games. That taste is eclectic, but also it's not overly broad. We are very much on the same wavelength when it comes to an aesthetic sensibility and a design sensibility.

When we do come into points of contact where we're in disagreement, both of us have a high respect for argumentation and for expertise. And so we'll just talk it out.

Part of this is we've been playing games together since we could walk. Not quite that early - there's five years between us. But Drew's the very first character I DM'd when I was in fourth grade and barely understood what I was doing.

Drew: Oh, yeah. Drew the Druid!

Cole: So we've been playing games for a long time and also we spent a lot of time talking about movies and music and art, all kinds. We're very much on the same page about those things. We also have a similar approach to culture more generally, which is very wide and deep - like, omnivorous, consume everything. I listen to a lot of music and so every week it's usually like two or three new albums. And I know Drew's the only person [also listening to those albums], so I'm like, "Hey Drew, what'd you think of the new Big Thief?" We talk through everything.

Drew: I do think that is actually such a cornerstone of why we've had such a harmonious working [relationship]. I have been absolutely spoiled to work with someone that I worked closely with. With a very similar ideology [and] philosophy from board game tastes down to structuring a company and cultural impact.

Cole: At Leder it's actually kind of the opposite. We have many different aesthetic tastes. Many different ideas about how games should look. And we argue a lot. We love arguing with each other. It's a little bit like a dialectic or something. We actually produce like some synthesis there. So I think that usually something good is going to come out of conflict and push. So I'm always very suspicious of the fact that Drew and I are so in lock about things. But we are relentlessly critical of our own work.

I don't care about the market. People who like the game? I don't care. I really care about how I think about the game and how Drew thinks about the game.

One of the people on our production team came over, myself and the developer at Leder, we're working through some new releases and kind of roasting them. Just privately. But being very critical for all of the new productions. And someone from the operations team come over and was, like, "Hey. Let's just- Positive. Smile on the face." Because from a marketing or a sales or production standpoint, we're all in the same boat. I had to tell the person that actually this reflection, criticism is critical. That if you want to make something good, you have to be absolutely unsparing about your work.

This is maybe glib - and Drew can tell me to not say this - but I don't care about the market. People who like the game? I don't care. I really care about how I think about the game and how Drew thinks about the game. And maybe people will like it and maybe they won't. But I think you get into trouble when you're like, "Well, folks are going to like it in this shape." So let's hit that young family demographic.

Drew: I'm not gonna disagree with that, in part because I think that's what makes us special. And that's why you and I both look up towards what Sierra Madre [Games, the niche original publisher of the Pax series and John Company] has made - an unrelenting, uncompromising design aesthetic. And it wasn't for everyone. They still made it work for the scale that worked for them. Less of a market disruption but more seeking out what it is to bring a product into a cultural conversation about games. That makes me more happy, more fulfilled and excited to see what Wehrlegig will turn into. In direct context to the pressures from Leder and pressures from the mainstream. It's more validating and justifying that what we're doing is fine as long as we keep it on our scale.

If you want to make something good, you have to be absolutely unsparing about your work.

Cole: Leder's interesting here too because we have tried very hard to keep that kind of critical spirit despite having some market success. And so whenever we're working on a game, even when we were working on the new Root expansion, there are moments where I have to say like, "Okay, what we're doing here is making the game less interesting and more balanced, but actually we need to make it sharper." And I wasn't offering a clarion call, everybody realised this. I'm not the only voice that's saying it. But because there are constant pressures to make it more approachable. It's like, "Well, let's make sure that we're true to it. Do we like the thing that we're making? Do we think it is good quality?" And then the market will follow. Just kind of not worry about it too much.

What are those games and design ideas that you want to push against - or go with and explore further?

Cole: The way I tend to think about it is there are a series of best practices that are being arrived at and they are informed by a few things. They're being informed by the market success of certain titles maybe five or six years ago. They're being informed by a lowest common denominator. That's a very rude way of putting it. It's not that. They're being informed by the commonality between a lot of successes.

There are a series of best practices that are being arrived at and they're being informed by the market success of certain titles maybe five or six years ago.

So Wingspan, Root and then Great Western Trail - I don't know, just like the last four games that blew up. What do all these games have in common? Well, you'd have a hard time with that particular group. But you could find a certain commonality and then you build a design around that commonality. They're being sensitive to low-risk publication. If you want to produce a lot of games and publish a lot of games, how do you design a game?

One of the things about the way I iterate is I will tear down a lot right up until the finish line. I'll be like, "Oh, we're scrapping this whole thing, we're gonna rebuild it." It's a very scary way to operate. And for a publisher there are always easier ways out. I'll use the example of an event deck. You're like, "Oh, this is where I want to put a lot of the colour of the game." But as you play, when someone draws a card that's like "You broke a leg", that's not a very good card, you don't want that card. So instead of making it so your character is slower you're like, "You broke your leg, minus two victory points." "Well, that's a little too swingy. Let's just make minus one victory point." So a lot of event decks, the more you play, the more they are in development, they get milder and milder and milder. Because what they're doing is they're optimising for fun and they're optimising against "feel bad" moments.

Games have this massive emotional range - why would you want to make the game just about the giggles?

From my own design aesthetic, both of those things are horrible things to optimise for. Whenever I am working at Leder, we have friends in or people are visiting or working on games, if ever people start talking about "fun" or "feel bad", I'm like, "No, you can't use those words." Because we're not trying to make the game fun. We're trying to make the game good. So "fun" to me is this word that doesn't really mean anything. Games have this massive emotional range - why would you want to make the game just about the giggles? You could do that too but, when you're optimising for it, you're going to remove a lot of the character of the project.

Drew: That's again influenced because we're omnivores of media and we're consuming. You're approaching designs with the influence directly of a lot of like arts.

Cole: Drew and I both absolutely love really sad things. [laughs] I want to feel moved or I want to go to art museum and have an experience. And games are much more intimate than a painting on a wall.

Drew: It's why it's an arresting experience to approach something like [World War I card game] The Grizzled, for example, that is presenting its argument and its case in a critical perspective. But it's still entirely approachable.

I want to feel moved or I want to go to art museum and have an experience. And games are much more intimate than a painting on a wall.

Cole: One of the things I think about when I'm working on a design is: what is the game's narrative range? How many different types of stories can we create? And, then, what's the game's emotional range? How many types of feelings can it create?

It's not that a good game has to have a big scope for both of them; we can do a good game that's very narrow. But Oath is a game with a massive scope, and so I want the thematic ambitions to be matched with narrative and emotional conditions that are all in step.