RPG lifepaths turn character creation into its own game

The Game of Life.

One of the hot new features in many tabletop games is the solo mode. Even before the worldwide pandemic, getting together folks for game night was a tricky proposition. For those nights when real life squeezes out fellow gamers, it’s nice to have an AI opponent to play. It’s not quite the same as playing friends, but it can be close enough sometimes.

Tabletop roleplaying games have a similar element of solo fun. Even if I’m not running a game anytime soon, it can be fun to read a rulebook and absorb details of the setting. It’s also enjoyable to create a character to get an idea about how a game might work from the process. Some RPGs take this idea a little further by introducing a game element into the character creation process. Often called lifepath systems, they help generate character concepts when a player is stuck on a blank page or often take a character down an unexpected route.

Lifepaths take the random rolls used by many RPGs and turn them into backstory elements. One character might have low strength because they grew up on a low-gravity space station. Another might have a high magic skill because their mother was the head of a famous wizard school. Lifepath games bridge the gap between the maths of a character sheet and the meat of a character background by offering writing prompts that touch on both elements.

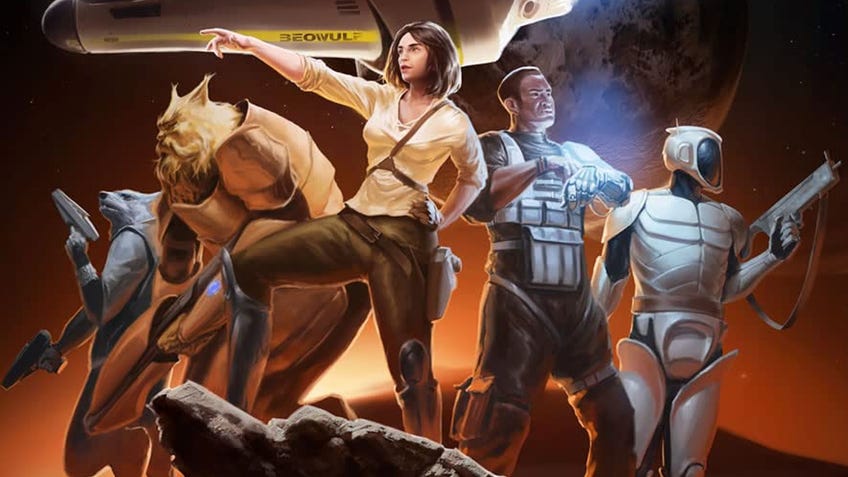

The most famous of these systems comes from the classic sci-fi RPG Traveller. If you’ve ever heard a grim chuckle about making characters in this space adventure game, here’s why: your character can actually die while being made. The character creation minigame is about risk and reward. For every term you roll up, your character gains more skills, equipment and cash. But the more terms you have, the greater chance your character will overstay their welcome and die before they get to the first session. The most recent edition takes death off the table but still keeps the risk sharp. Bad luck means you might end up with an injury, an enemy or other negative story hook the GM will gladly enjoy using.

Lifepath games bridge the gap between the maths of a character sheet and the meat of a character background.

R. Talsorian’s Interlock system, which powers the Cyberpunk games, takes the lifepath in a more melodramatic direction. It focuses on a character’s history by creating important events, allies, rivals, lovers and haters. These lifepaths understand that while players might drool over cool cyberware and big guns, the stories thrive on the people and communities. It’s one thing for a mysterious suit to offer the edgerunners a job hacking into a corporate data fortress. It’s another thing when it’s a favour for your long-thought-dead parent or the person your character still loves even though they’ve sold you out to the company before. Those personal details are more likely to bring players into a story as they flesh out the details of these relationships.

Lifepaths aren’t all in the past, either. One of my favourites comes out of Star Trek Adventures from Modiphius. (Full disclosure: I did some design work on the game, but didn’t see this part until the general release.) It’s somewhat of a callback to the original Star Trek: The Role Playing Game, since that also had a lifepath that worked out previous tours of duty, but what makes Adventures’ stand out is how players have a choice during each step. For example, they can choose to accept their upbringing or reject it. Each choice gives the character a different set of abilities. Growing up in Starfleet and accepting it means more precise skill, while rejecting it means the character turns out a little more bold and self-determined.

These paths also offer an opportunity to connect groups through common experiences and NPCs. If two characters roll that they survived an episode with a godlike alien, why not discuss how they were on the same ship when it happened? If one player has a rival fixer gunning for them and another has a fixer as a lover, could they be the same person? Mongoose’s Traveller, the 2008 update to the classic, encourages this sort of thing by giving players who link up their backstories an extra skill bump. Pre-setting backstory like this gives groups momentum out of the gate rather than spending early campaign sessions forming bonds instead of kicking butt.

There are players who lovingly handcraft each character that might be appalled by leaving so much of a character up to chance. To them I say: try a lifepath once. It’s good to play characters outside of a comfort zone and a refreshing creative challenge to make a character type that you usually don’t. We all still have characters we prefer to play, but a lifepath offers a glimpse of being cast against type or stretching your creative muscles to make something you normally wouldn’t choose to play work for you. Think of it like an album from your favourite musician trying to branch out, or your favourite comedian taking a serious role to broaden their cinematic appeal.

Assuming, of course, you don’t end up dead after spending one too many terms in the army because you wanted a chance to take your favourite plasma rifle home with you.