How an RPG is written makes a big difference to how it plays

Textual feeling.

Think about the last roleplaying game you read. I don’t just mean played, or peeped at the mechanics, or were taught how to play; I mean read. Probably not front to back, because lord knows that’s hard to do for me, but at least where you sat down and engaged with the text itself. There’s a lot of discussions around reading gamebooks – some, including myself, even consider the act of reading a game to be a kind of play, and others find it surprising when someone says you should “read the rules” as a piece of genuine GM advice.

The truth is, reading an RPG can give you a whole new kind of insight into how it works and what it’s saying, and a game’s tone and diction can have an effect on the way you play it.

Think about how its words functioned, then think about how they felt. Consider the ways the words on the page gave you instruction and how the way those instructions were written got you to feel as you read them, planned and played.

Don’t just think about the mechanics, lore or flavour text but specifically think about their tone.

Every piece of text in the world has a tone, and roleplaying games are no exception. From the clinical detail of Burning Wheel to the acid-rock psychedelic poetry of Necronautilus, the diction of an RPG’s rules doesn’t just establish explicit mechanics (the things you, the player, do - like rolling dice and moving mice) and implicit mechanics (the implied “why” of doing them) on layers in and out of the game. They also craft up a third kind of mechanic that sits even more directly between you and the game as a whole - something I’ve taken to calling “meta mechanics” - and these primarily exist through the voice of the designer presented via a game’s text.

I don’t mean “meta” as in “self-referential as a meme”. I mean “meta” to describe something that exists as a part of a whole that references, effects, and plays upon the thing itself. This mechanic, the voice of the designer, sits alongside and between you and the game and shapes the way you interact with and envision the world.

Text in a game doesn’t just tell you how to play the game or why your characters are doing something. It also gives a subtle (or, let’s be honest, unsubtle) kind of guidance for how you should interact with and relate to the game. A mechanic that exists outside of the text but that shapes it as strong as anything.

Games with more clinical, distanced text present as though they’re asking for very considered, procedural relationships. They ask to be treated with a kind of arms-length professionalism and focus on execution.

Reading an RPG can give you a whole new kind of insight into how it works and what it’s saying.

Games with flowery, lyrical writing yearn to be explored and considered in different ways; they ask you to consider the poetic and emotional side of things.

Even though both of these games may have “Gain 2 extra dice” somewhere, the way that mechanic is presented makes it feel different - and by extension gets you, the player, to consider things differently.

A game with bright, zany instructions will get the table joking (if it does it well), while a darker voice may have you highlighting sad truths through comedy during your play. Think about Fiasco versus Inhuman Conditions. Fiasco asks you to escalate and escalate by using dramatic irony and ever-worsening situations - it’s outright comedic and gets everyone ready to joke - while Inhuman Conditions leans into discussions of totalitarianism through metaphor and in execution can end up being either darkly comedic or strict and serious.

Both are party games, and their voices consistently help push you towards the type of engagement the designers want you to have.

A game’s tone is a bridge from designer to player.

To speak more directly towards the effects of voice on explicit mechanics, let’s revisit the earlier example of “Gain 2 extra dice”. Think about how the feeling of that phrase changes when you tweak the words a bit. Compare:

- Gain 2 extra dice.

- When you struggle, gain 2 extra dice.

- When you fight and claw and scream for an advantage, gain 2 extra dice.

These all do the exact same thing: give you two dice. It’s simple, straightforward and it doesn’t need anything more - but by adding the extra descriptors, the tone of the game is solidified and has the players considering extra aspects and leaning into the voice of the RPG.

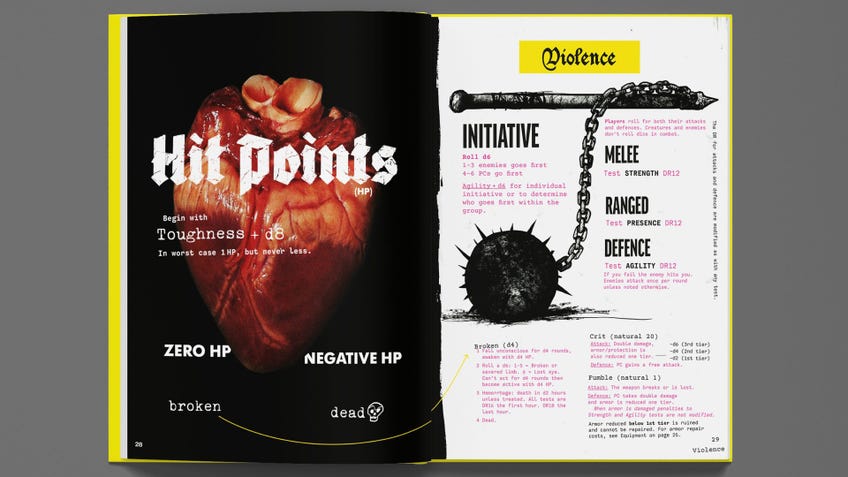

Think about the way Mörk Borg describes items and treasures in its tables compared to how Blades in the Dark describes the tools your scoundrels have readily available. In Mörk Borg, the text is visceral and descriptive in a way that makes you feel the disgusting and twisted nature of the world. In Blades, though, the tools are described with a kind of clinical matter-of-factness.

The set of keys you find in Mörk Borg is caked in blood and rust, the jingle of their movement dull, and looking into the eyes of the skeleton key sends shivers down your spine. The same set of keys in Blades is copper and made to fit the locks just so.

There are so many roleplaying games to explore, and an infinite number of ways to use words to affect the players at the table. A game’s tone is a bridge from designer to player; an invitation to lean into the ideas and fiction of a world and its mechanics. The voice of a game’s text is so core to establishing and emphasising the core themes of a game that to not consider it during design or play is to miss a major opportunity to gain extra buy-in and set the game apart.