Old stories, new forms: Rewriting folklore as RPGs brings fresh perspectives and cultures to the table

“What is an RPG, but a seed of imagination designers give to players and game masters so they can grow gardens of their own?”

Think of an old story. Not just old to you, but a story that’s old to the world; one that’s been twisted, retold and passed down around fires and thunderstorms. Think in myths, folktales and old wives’ tales. The kinds of stories that might have started somewhere in a cave but ended up at your doorstep, talking about the creatures living in the woods, in the alley, in the sewers.

When game designers write about folklore, they are in conversation with stories that are so old that they defy authorship. When people play games based on these stories, they become a part of that storytelling tradition. Folkloric roleplaying games have always been popular (Dungeons & Dragons didn’t invent dragons, after all) but with platforms like Itch.io making small, indie RPGs globally accessible, more and more games are coming out based on very specific folktales. Many of these games are so indigenous and geographically-focused that it would be impossible to find, or even replicate, these stories outside of their home context. That’s where game design comes in.

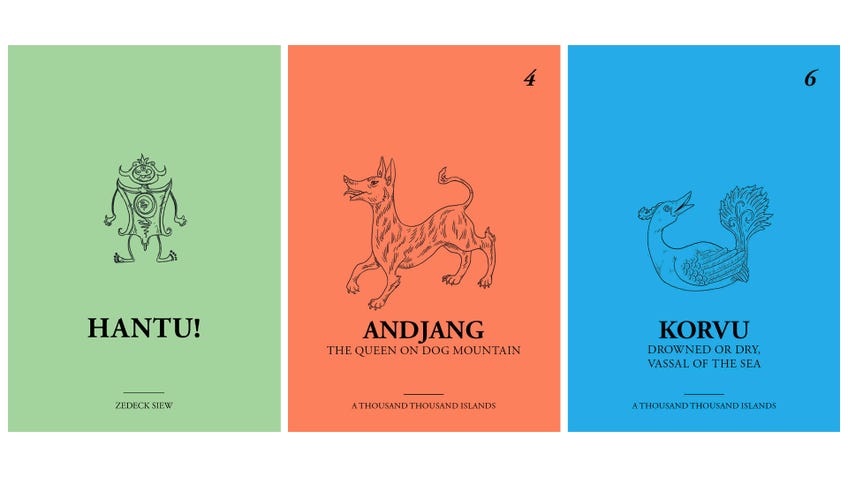

Zedeck Siew is a Malaysian writer/designer known for his project A Thousand Thousand Islands, a series of zines that detail system-agnostic settings, scenarios and adventures, created in collaboration with artist Mun Kao. Siew’s work is, in his own words, “planted in the customs, histories, and material cultures of pre-colonial Southeast Asia. Out of this compost we imagine new worlds - different, but ‘nearby’, in spirit.”

‘Nearby in spirit’ is an eloquent way to describe folkloric RPGs. Finding frameworks within folklore helps designers offer games that can be used in many different settings, against many different stories. “Folklore has conceptual shapes we try to learn from,” says Siew.

Using cultural touchstones as a starting point is a way to bring people to the table and set expectations from the start. Learning how to change those expectations while still preserving the “cultural shape” of folklore is a challenge that Siew, and other designers, grapple with.

Playing the same RPG multiple times is like witnessing folklore changing forms.

Ultimately, when people come to the game table, there is an opportunity to take control of the narrative. There is a chance to learn about a story and then make it your own. But ownership is a hard thing when it comes to stories - and even more so when it comes to a collaborative RPG, where everyone at the table has stakes in the narrative. The key to these games is understanding that ownership isn’t necessary to tell a good story.

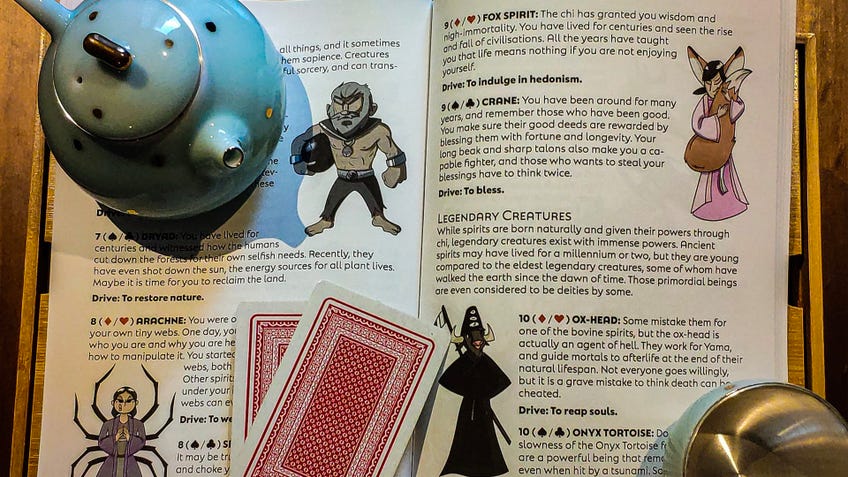

“All stories transform and evolve [when] they are told,” says W.H. Arthur. “The folklore you learn nowadays is probably very different from its original form. […] Playing the same RPG multiple times is like witnessing folklore changing forms.”

Arthur’s own games are often rooted in Chinese mythology, but with a twist. The Sol Survivor takes a classic story and reverses its perspective. Traditionally, the myth follows Hou Yi, a legendary archer, as he shoots down nine suns in order to save Earth from a drought. Sol Survivor asks the table to share control of one of the shot-down suns as they attempt to return to the sky.

Shifting points of view and re-defining heroism is a common theme in contemporary folkloric RPGs. Arthur asks, “Are the actions of the "heroes" from folklore really justifiable to the people who are affected by them?”

Reversing the narrative control in RPGs (such as focusing on the shot-down Sun instead of the archer) is a way to invert power structures commonly told in mythology. When players are allowed, or even encouraged, to rewrite these power structures, playing folkloric RPGs can become a subversive act.

Anna Landin agrees wholeheartedly. While many folktales re-iterate the power structures, gender roles and xenophobia of the time and place in which they were told, there’s a lot to be said for moving on. “Building an RPG on the framework of folklore allows people to examine [these stories] from a new angle. It allows [players] to bend and shape that folklore to suit them. Being the storyteller means having power over the story, and there is a lot you can do with that power.”

Being the storyteller means having power over the story, and there is a lot you can do with that power.

Her game, The Conjurer’s Cloak, is a fantastic example of this. In the original story, the heroine defeats the villain through her unassailable virtue. But, Landin says, “In writing that game, I gave the players the task not of convincing the conjurer to give up his evil ways, but of directly breaking and unravelling his power.”

Subversive actions happen at the table. Inviting people to change the narrative is an important, if not intrinsic part, of playing folkloric RPGs. “Inviting people into a space where before, they had little power, and handing them the tools to shape that space is a way to lend them power,” Landin continues. “Approaching folklore as a marginalised person can be tough - we often see ourselves only in the helpless victims, or in the monsters. And while there is a lot to be said for the subversive power inherent in taking on the role of monster - sometimes we want to be the heroes, too.”

Folkloric RPGs also invite a cultural exposure to stories that people might not have heard before. Siew has a lovely metaphor for what this means. “I try to think in terms of open invitation. I'm working in my garden. I can't address you; I'm busy shovelling the shit of my own context. But come sniff at the flowers, if you want? Take a seed. And what is an RPG, but a seed of imagination designers give to players and game masters so they can grow gardens of their own, to care for at their own tables?”

For players that come from the same cultural background and language, folklore-based RPGs allow them to deeper explore intricacies of said folklore together.

Game design outfit Għar Gremxul is run by an anonymous Maltese designer who focuses on creating games that are rooted in his culture. He had some great insight about how folkloric RPGs can contribute to different kinds of cultural exchange depending on who engages with the work. “For players that come from the same cultural background and language, folklore-based RPGs allow them to deeper explore intricacies of said folklore together. Between players from the diaspora, it allows them to engage with their culture on a more personal level (and also explore differences in folklore between diasporic populations!). Between players that are not a part of that culture, it allows them to engage with the culture's folklore and traditions as presented to them by designers, exploring a world that they may not have been aware of before.”

There is a kind of fascinating wonder within folkloric RPGs. There’s always a ‘what if’ in any roleplaying game, but for designers who engage with folklore in their writing, that ‘what if’ becomes deeper and more intricate. There is history to take into account. A way that things have always been which needs to be addressed within the text or at the table.

Sarah Doom and Marissa Kelly, who along with Whitney “Strix” Beltrán helped design the game Bluebeard’s Bride, a direct reimagining of the French folktale, were both asked about why folkloric games have gained such a foothold in the contemporary game design world. “Games give us permission to explore the unfamiliar in a familiar fashion,” says Doom. Kelly adds, “Myths and legends allow us to explore boundaries and morals through the experiences of another. […] You can tell your own version of an old story and still be surprised by what you find.”

To write and play within an old story gives it new meaning. To be able to hold a game in your hands and know where it came from - that it has history, that these stories are storied themselves and give narrative power to the people at the table. Ultimately we can subvert the stories we’ve been told, turn the old fables on their heads, and give them back as something better, new, improved - and ours.