Dungeons & Disabilities: Can tabletop RPGs redeem their problematic portrayal of disability?

“When including more diverse representation, disabled people continue to be excluded at alarming rates.”

When I played Dungeons & Dragons as a teenager in the late ‘90s, one of our fears was becoming disabled. It's a stance that makes me cringe today. At the time, the idea of creating a character with disability or chronic illness was unthinkable; for many players, disabilities in tabletop games were often portrayed as being for NPCs or villains. Even today, a hero with disabilities is rare - if ever - to be found in the gaming world. The mainstream media has been successfully clamoring for more diversity in terms of race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation and age, exemplified by the efforts of the #OscarsSoWhite and #MeToo movements, but how about people with disabilities, chronic illnesses and neurodiversity?

State University of New York professor Shelly Jansen Jones, PhD, studies tabletop games with a focus on Dungeons & Dragons. "I think gaming is a subset of mainstream media and therefore often relies on or is influenced by societal trends and standards,” Jones tells Dicebreaker.

In 2018, Jones published the article Blinded By The Roll: The Critical Fail of Disability in D&D on Analog Game Studies, pointing at issues within Dungeons & Dragons’ system. Regarding the industry’s representation of disabled folks, Jones believes that “resorting to the harmful stereotype that villains have a disability [...] is simply a sign of lack of creativity. Disabilities are often villainized or pitied instead of recognised as a natural part of life and something that could, quite frankly, happen to anyone at any time.”

Since 2013, American Erin Hawley has been operating as a tabletop games reviewer under the title of The Geeky Gimp while living with muscular dystrophy, scoliosis and anxiety. As she stoically puts it: “I have good and bad days, like anyone else.”

Asked how disabled people are represented in tabletop games, Hawley doesn’t mince words: “I can’t think of any good reps of disabled people in tabletop gaming. And mental illness is often portrayed as dangerous, quirky, and/or scary - not just in games, but literally every medium.”

In April 2020, Canadian author Allison Alexander released the book Super Sick: Making Peace With Chronic Illness, a work focused on how relevant it is to have portrayals of chronically ill people in media. Alexander has Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) as well as chronic fatigue, pelvic pain, iron deficiency, anxiety attacks and other maladies. Through all this, she has a hobby: adventuring as a dark elf sorcerer in D&D.

I can’t think of any good reps of disabled people in tabletop gaming.

Alexander explains that, while she can only speak for herself, tabletop games have always been an attractive activity since they don’t require much movement. One of the standout virtues of these games are the relationships they can create.

“It's probably not a coincidence that most of my close friends are gamers, as gaming is a lovely way to bond and spend time with each other,” she observes. “Pre-COVID, my D&D group was kind enough to meet at my home every session so that I didn't have to make the effort to leave the house; when my health gets really bad, which it has been for a long while, it takes a lot of energy to go out, and it's easier for people to come to me.”

“Spoonie” is a term created by Christine Miserandino in 2003 for chronically ill and disabled people hacking systems - including their own bodies - to live in the best way possible. They are also called “spooniehackers”: genuine lifehackers inventing new, unique and adapted ways of making it through life in a world often unreceptive to them.

Accessibility, no matter what medium, is never one-size-fits-all.

Every spoonie experiences gaming in their own way, as Hawley confides: “For me, modern tabletop games are often difficult to play because of the number of pieces, size of the board and any real-time game mechanics. I can roll dice, I can flip cards, but just some games I need total help with. The very nature of board games means people with physical disabilities may not be able to access them. Unlike a video game, where you can interact with different modes, use assistive devices, etc., tabletop games don’t really have that accessibility.” It’s a community regarded as “invisible”. “Accessibility, no matter what medium, is never one-size-fits-all,” Hawley adds.

Pressed as to how spoonies are portrayed in mainstream media, “stereotyped” is the first word that comes to the mind of Brazilian sociologist Cláudio Coelho of Cásper Líbero College. According to Dr. Coelho, these one-sided approaches misrepresent the experience of being disabled and can be harmful - even “when the intention is to show them under a sympathetic light”.

On the possibility of tabletop games bringing marginalised individuals or groups to mainstream society, Coelho believes that it can happen only if they are portrayed with complex aspects of their lives - leading to greater identification and acceptance. Hence, spoonies who are currently perceived as outsiders may feel a sense of really belonging.

Meeples or figurines are usually of abled people.

Although the mainstream image of “nerd” culture has improved over the years - one can compare how D&D players were portrayed in 1980s movies and series to Netflix’s recent Stranger Things - the tabletop hobby still endures some prejudice. It can also be prejudicial itself, with inside cliques and toxic fandom, believes Jones. This harmful behaviour can be targeted at spoonies who already endure societal stigma, and are unable to find relief in the community.

Alexander and Hawley note that chronic illnesses, disabilities and neurodiversity are often portrayed as impairments to characters in tabletop RPGs. “Meeples or figurines are usually of abled people,” points out Alexander, who also sees the game mechanics for disability and mental health conditions as “inaccurate”.

Jones perceives “conditions” mechanics, ranging from paralysis to blindness, as “punitive” and as possible to “magically” undo, while the “madness” table is a problematic collection of psychological and physical conditions piled up as a way to castigate characters. For the scholar, the gaming system resorts to ableism - the assumption and prejudice surrounding the ability and perception of those with disabilities. D&D subtly promotes this view through its gameplay mechanics and stereotypical representation of disabled NPCs.

Jones plans to return to these studies but in the interim, she has registered a few proposed changes to the roleplaying industry. In April of 2020, when questioned publicly on the depiction of D&D character Ezmeralda in Curse of Strahd, Wizards of the Coast’s Chris Perkins responded that the staff would “fix that”. The vampire hunter lost one foot to a wolf bite and uses an enhanced prosthetic substitute; in visual representations, she is shown as a strong character, while the text puts her under a negative light, as she “takes care to hide it from view”.

Jones has yet to comment on the revised version of Curse of Strahd released in October. (This year's recent Van Richten's Guide to Ravenloft reportedly further addresses Ezmeralda's depiction.) Still, she is keen to examine to what extent the module was updated with respect to disability representation and “the problematic portrayals of the Vistani, a people stereotypically modeled after the Romani” that includes Ezmeralda.

D&D is experiencing a mea culpa moment in its rendering of races, particularly with regards to orcs and dark elves - the former as dim-witted and driven by bloodlust, and the latter as scheming and backstabbing. On the other hand, Jones’ paper acknowledges progress on gender diversity.

For a game that relishes offering insights on the stats, history, lore, and quirks of multiple races and classes of characters, D&D 5E is silent on any possibility of being 100% able-bodied.

“D&D 5E has made wonderful strides toward making their product and gaming gestalt more inclusive. But for a game that relishes offering insights on the stats, history, lore, and quirks of multiple races and classes of characters, the game is silent on any possibility of being 100% able-bodied,” Jones concludes in her article. She believes that the same effort made to include other underrepresented players should be applied to disabled ones.

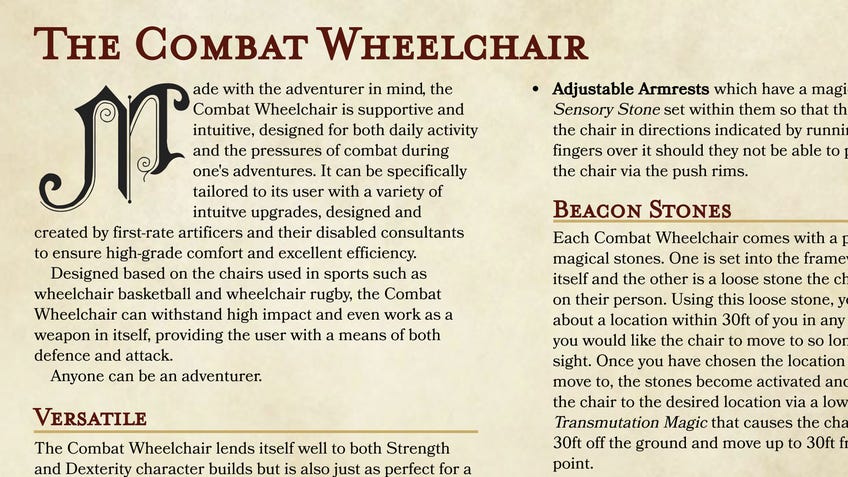

Last year, another attempt to bring disabled folks to the tabletop arrived in the form of a combat wheelchair for Dungeons & Dragons 5E by RPG designer, writer and modder Sara Thompson, who designed the rules, and Strata Miniatures, which sculpted a range of figures based on Thompson's creation. The invention was met with backlash from a part of the community, who expressed unfounded belief that a RPG with characters who can ride griffons to fly through the wind while wielding magical axes and shooting fireballs with ease could not include combat wheelchairs, and praised, especially by players dealing with disabilities and their party colleagues.

In 2020, the world was ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic, and tabletop gaming became even more of a relief for people, especially those living with difficult conditions. During the pestilence, Alexander’s group didn’t stop and are experimenting with online gaming meet-ups through Zoom and Roll20. She also still plays board games with friends using Tabletop Simulator on Steam.

Incorporating sensitivity readers or hiring disabled gamers to be content creators in some way would go a long way to creating a more positive representation.

“My hope is that people realize the alternatives to meeting in person that are available to them, and make more use of these technologies even after the pandemic is over,” Alexander affirms. “We should be willing to sacrifice meeting in person for someone else’s safety.”

If the health crisis is pushing the tabletop games business to different solutions this industry still has to consider representation. Alexander believes that “many ableist tropes and mechanics happen simply because the creators don’t know any better” and it would be beneficial if developers were more informed and inclusive when creating games.

Hawley maintains that while more people may be considering and discussing accessibility, designers may still not know how to properly “implement accessibility in their board games”.

“Lack of representation in media, and tabletop games, is something that still has a long way to go,” she says.

“Incorporating sensitivity readers or hiring disabled gamers to be content creators in some way would go a long way to creating a more positive representation,” urges Jones. “This is not a unique situation to [Dungeons & Dragons publisher] Wizards of the Coast or to any content creator and I think there is some (minimal, unfortunately) initiative to include more diverse voices in content creation. However, when including more diverse representation, disabled people continue to be excluded at alarming rates.”

Thanks to Emma Steer for their assistance with this article.