The authors of Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre were roleplaying long before Dungeons & Dragons

My one dream, my only dungeon master.

In 1845, two years before Wuthering Heights was published, Emily Brontë shared a train trip to York with her sister Anne, who was two years out from publishing her first novel Agnes Grey. To pass the time the two sisters played a game they'd enjoyed since they were children, which Anne described in her diary like so: "During our excursion we were Ronald Macelgin, Henry Angorra, Juliet Angusteena, Roseabelle, Ella and Julian Egramont, Catherine Navarre and Cordelia Fitzaphnold escaping from the palace of instruction to join the Royalists who are hard driven at present by the victorious Republicans."

They invented characters with luxuriantly fantastical names - Roseabelle Egramont is your next tiefling rogue in D&D, you're welcome - and told stories of dramatic escapes and revolutions. It was all part of an ongoing saga started with their older siblings Charlotte and Branwell years before. They told stories about these characters but, more importantly, as Anne wrote, they "were" them, embodying the imaginary heroes. It may sound closer to a game of ‘let's pretend’ or a creative writing exercise - and it was both of those things - but this imaginative fantasy of the Brontës' creation also had a lot in common with a modern tabletop roleplaying game.

They felt very connected to their characters, and used alter-egos to tell their stories and roleplay.

Emma Butcher is a historian and the author of The Brontës and War: Fantasy and Conflict in Charlotte and Branwell Brontë's Youthful Writings. She traces the origins of the Brontës’ game to 19 years before that train trip. "In 1826," she says, "the father of the Brontës brought home a box of toy soldiers - this was the beginning of their saga and they would act out early stories using these as props on the moors. They would also act stories out in the parsonage where they lived, be it in bed or around the fireplace."

Branwell Brontë owned a collection of miniatures any Warhammer player would be proud of, and when his father brought home 12 toy soldiers as a birthday present he shared them with his three sisters. Each sibling chose a miniature and named them. They became Bonaparte, Gravey, Waiting Boy and the Duke of Wellington, and were the first inhabitants of a land eventually dubbed the Glass Town Confederacy and sketched out by Branwell on a map that needs only a hex grid to look at home in a tabletop RPG supplement.

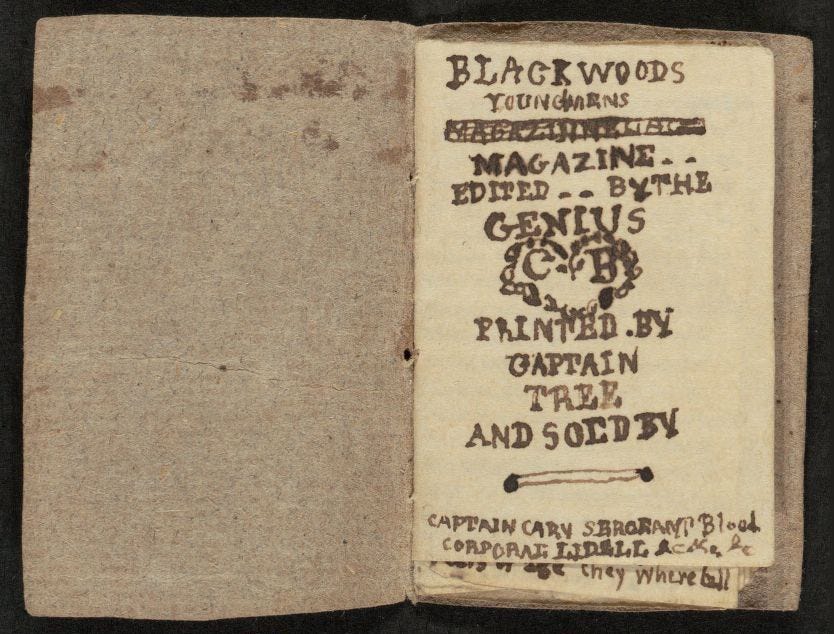

Sometimes the children used the toy soldiers as their surrogates; at other times they inserted themselves as giants or genies towering over them. They fluidly moved between characters, recasting themselves as the leaders of separate islands, each with its own Glass Town. As well as playing these stories together while walking the moor or lying in the beds they shared, they wrote some of them down in tiny, matchbox-sized books.

Some historians have suggested the books were so small because they were made to the scale of the soldiers, while others think they were small to save paper, which was expensive at the time. A third theory is that they were designed to be unreadable by the children's short-sighted father because, alongside the recountings of coronations and exiles, they included racier material, battles and affairs. In a way they resemble the much later "bluebooking" described by designer Aaron Allston in his influential 1988 Champions RPG supplement Strike Force: the shared journaling that allowed his players to imagine lives for their characters beyond the table and include romantic elements that teenage players pretending to be superheroes would have balked at.

The Brontës aren't the only literary figures to invent their own world to play in as children. Butcher compares their books to the Hyde Park Gate News magazines produced by a young Virginia Woolf and her family, and the writings Hartley Coleridge, son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, produced about a continent called Ejuxria. "The Brontës’ worlds are very special, however," she says, "in their size and the amount that survive."

In those tiny books they came to call the Blackwood's Young Men's Magazine, the older siblings, Charlotte and Branwell, tended to write about deaths, battles and brooding, Byronic exiles, and looked down on their innocent little sisters' contributions. Writing as one of her characters, Charles Wellesly, Charlotte visited Emily's island nation of Parry's Land and lamented that, "instead of tall, strong muscular men going about seeking whom they may devour, with guns on their shoulders or in their hands, I saw none but little shiftless milk-and-water-beings, in clean, blue linen jackets and white aprons".

We can deduce that this was a full-scale developed world.

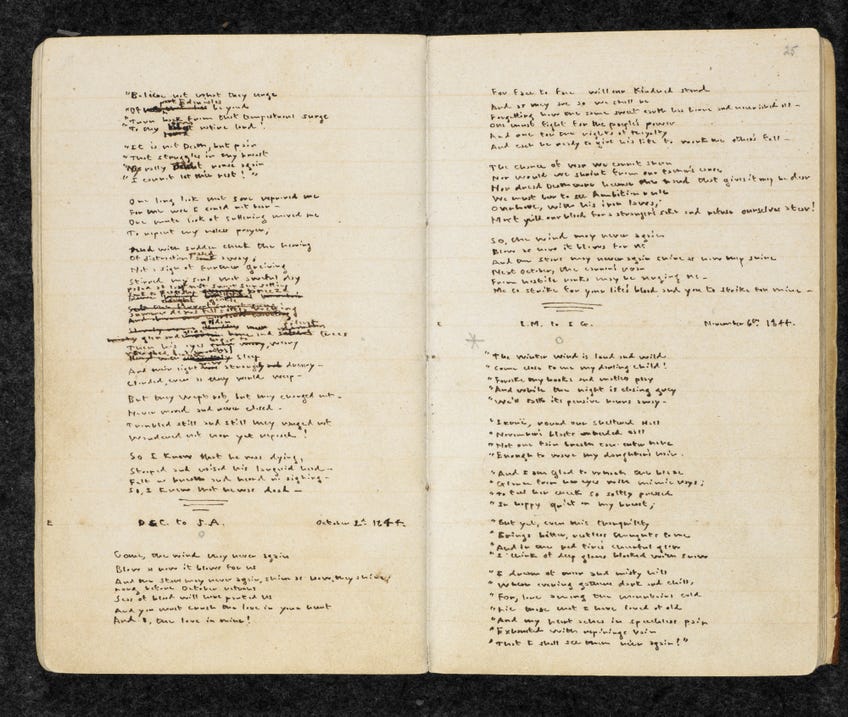

Emily went on to create the tall, strong, muscular, gun-toting woman-devourer Heathcliff years later in Wuthering Heights. But at the time Charlotte and Branwell were trying to make the game more mature - if Vampire: The Masquerade had existed in the 19th century they would absolutely have played it. Once the older siblings left home, Emily and Anne, sick of being sidelined and mocked, created a new world called Gondal while Charlotte and Branwell rehomed their Glass Town characters in a more mature setting called Angria. We know about this because of how frequently it appears in their letters: an early play-by-mail game.

"Glass Town and Angria are very extensive," says Butcher, "there are over 10 years worth of work written by Charlotte and Branwell where they are constantly responding to one another. These dual narratives are also accompanied by poems, plays, artwork and other ephemera. Gondal is more complicated as only the poetry and some artwork survives. It is predicated that there was a huge amount of prose to accompany this, but it has since been lost. From the poetry, however, we can deduce that this was a full-scale developed world."

In their earlier games, characters sometimes died but were resurrected, often by genies (the young Brontës went through an Arabian Nights phase), but sometimes by a body-snatching doctor named Hume Badey who possessed a "macerating tub" able to revivify the dead. Resurrection magic was as commonplace in Glass Town as in a typical Dungeons & Dragons 5E campaign. But when Charlotte and Branwell began their play-by-mail game of Angria, Branwell's love of offing characters in battle became an issue. When Charlotte's beloved Duchess was killed, she wrote about it in her diary: "Is she alone in the cold earth on this dreary night? I can't abide to think how hopelessly & cheerlessly she must have died." She sounds as bereaved as any roleplayer who has lost a favourite character.

Butcher agrees that there's a lot of common ground between the Brontës' games and modern tabletop RPGs. "Absolutely," she says, "these stories are grounded in imagination and simulation. They felt very connected to their characters, and used alter-egos to tell their stories and roleplay. These were not fragmented stories but each had a long back story. In each tale characters and events were expanded and incorporated into new plot lines. Equally, the collaborative nature of these sagas meant that it was propelled by how each writer/player responded to new developments in the plot line."

Though they did it without dice and dungeon masters, over 100 years before Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax explored their worlds of Blackmoor and Greyhawk in Dungeons & Dragons, the Brontës were roleplaying in Angria and Gondal.