‘Broken’ board games are better than boring ones

For balance.

“Unbalanced.” “Broken.” “Luck, not skill.” Look in the comments section of any board game website and you’ll find these common complaints. For a number of players, tabletop games can’t be fun unless every element of luck, unfairness and potential frustration is permanently consigned to the designer’s drafts folder.

Smoothing a game’s rough edges can make it a hardened diamond, impossible to crack without the laser focus of a strategic mind, an equally-matched opponent and hundreds of hours of experience. There’s a reason that chess doesn’t have dice, that Go doesn’t feature a spinner in the centre of its board. The tabletop will always have a place for games of pure skill, with rules so sharp they’d cut through the fabric between dimensions if you dropped the box.

Yet for every immaculately formed Hive, Sh?bu or Tak, there’s a dozen bland - if mechanically functional - cookie-cutter worker-placement Eurogames, sweeping strategic wargames or dice-chucking dungeon-crawlers. They’re the Olly Murs of board games: perfectly adequate at what they do, unlikely to offend anyone and utterly devoid of personality. And god, are they boring.

A fine line lies between frustration and fun. Nobody wants to emerge from a board game night having spent several hours waiting to draw the right card or roll something higher than a 3. There’s no denying that truly “broken” games do exist, with certain unwinnable game states or unresolvable situations slipping the playtesting net and leading to experiences that leave nobody willing to play again.

What someone who has played a game a handful of times decries as “unbalanced” or “broken” can simply come from a lack of familiarity.

As a number of game designers will tell you, though, what someone who has played a game a handful of times decries as “unbalanced” or “broken” can simply come from a lack of familiarity. There’s almost always a potential counter-strategy or catch-up mechanic keeping things fair, even if you don’t see it at the time.

In other cases, the game simply isn’t designed to always be fair. A weak first turn in Food Chain Magnate can leave you chasing the rest of the group for the next three hours, with your only hope being that they similarly stumble later on. Not every game aims to let players’ skill be the sole deciding factor in whether they emerge victorious, either. No matter how many points you plug into your questing fantasy character, the teetering of a die or draw of a card can turn your otherworldly show of strength or acrobatic feat worthy of a slow-motion replay into a banana-peel pratfall as your warrior misses a sword swing, bumps into a wall and impales themselves on their own blade.

The important thing is making these moments memorable and enjoyable in their own way. Failure has to mean something - whether it’s baked into the rules or simply a funny story to tell later. Horror game Betrayal at House on the Hill is notorious for its vague rules and the inconsistent B-movie quality of its haunts, but even its iffiest scenarios tend to be entertaining. Instantly losing because the person next door happened to have a stick of dynamite on them when the haunt began can leave more of a positive impression than executing an effective but dull plan over the course of 40 minutes.

Failure has to mean something - whether it’s baked into the rules or simply a funny story to tell later.

Accounting for players’ bad luck is one aspect, but throwing off the balance from the beginning can be its own reward. Seventies classic Cosmic Encounter is legendary for a reason. Packed with dozens of unique alien races, each with their own abilities and even win conditions, it’s a wild game of discussion, alliance, betrayal and contradictions - both between the players and in the game’s own rules.

By its designers’ own admission, Cosmic Encounter is by no means fair or balanced. That’s why it’s endured - as its lasting influence on big-name games such as Magic: The Gathering and this year’s release of a two-player spin-off proves. Seeing how your particular combination of aliens will break the rules this time around remains as brilliantly chaotic as ever. The holes in the rules deliberately spill the fuel - the fun of flicking a match into the explosive setup is left to the players.

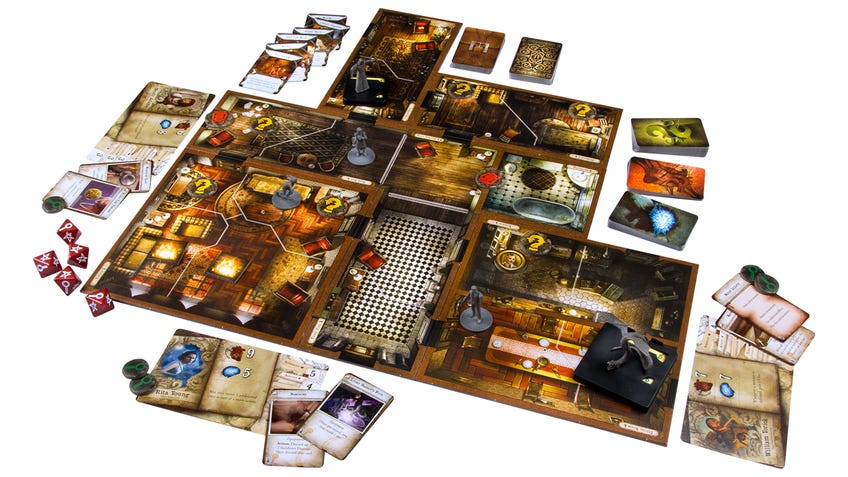

Sacrificing balance at the altar of atmosphere can be an effective way of capturing a specific mood on the table as well as around it. The Arkham Horror Files games - particularly Eldritch Horror and Mansions of Madness - use a flagrant disregard for fairness to capture the doom-and-gloom tone of their horror tales, as players’ investigators struggle against overwhelming odds to defeat all manner of otherworldly terrors and save the world. At points, things can be almost punishing. In another game, facing such a miniscule chance of success hour after hour might feel deflating. But when failure is the expected default, beating a clearly rigged deck tastes that much sweeter. Nobody expects everyone to make it out alive from a horror movie, after all.

Isn’t leaving some impression better than leaving none at all?

Sometimes you need those rough edges. It might mean you have a few playthroughs where things are frustrating, confusing or overly drawn-out - but isn’t leaving some impression better than leaving none at all? Personally, I’d always prefer to spend two hours playing an entertaining game despite its flaws than yawning through another “absolutely fine” design searching for that extra dash of spice that never comes.

Like a teetering house of cards held together by a hope, prayer and a few atoms of laminate, a perfectly balanced game can be its own reward. Often, though, it’s much more satisfying to watch the whole thing come crashing down.