Scythe’s Automa designer on making cardboard AI feel human in solo board games

Singular achievement.

One of the most attractive qualities of the board gaming hobby is the face-to-face interaction that comes with it. The feeling of in-person competition and the thrill of out-thinking your opponents is something that video games could never hope to replicate, even in the glory days of couch co-op. However, there exists a growing sector of tabletop gaming that appeals to those who prefer a more solitary experience.

Solo board games have exploded in popularity in recent years. In fact, the 1 Player guild on BoardGameGeek is the most populous on the site, having earned that distinction sometime in the last year or so. At one point in the not-too-distant past, the idea of playing a board game by yourself would have been unheard of. Laughable, even. Not today, though. Today, solitaire board games are just as viable an entertainment as spending an evening playing the latest single-player video game campaign, watching a movie or binging your favourite Netflix series.

There are several reasons solo gaming might be an attractive pastime, but for Morten Monrad Pedersen, it provides a unique perspective on the designer tabletop hobby and an opportunity to escape the tension of day-to-day life.

“Solo games allow you to enjoy gaming in another way,” Pedersen tells Dicebreaker. “For me solo gaming has become a way to unwind when I’m stressed, to feel better when I’m down, and to recharge my social introvert batteries.”

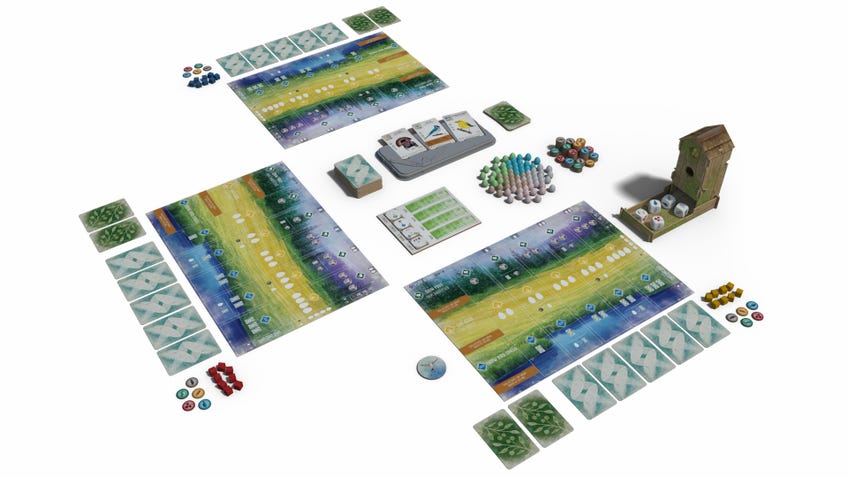

Pedersen is a game designer. Specifically, he manages a group of dedicated enthusiasts - collectively known as Automa Factory - that specialise in creating solo experiences for some of the most popular modern board games, including Viticulture, Scythe, Wingspan and Tapestry, among many others. Automa Factory derives its name from the Latin term automa, the root for the English words automate and automatic.

“Our goal is to make the solo mode feel as much like playing the multiplayer game as possible without overloading the player with rules and extra work,” Pedersen explains. “Our first key principle is that we believe that the best way to keep the feel of the game is to have an artificial opponent, we call ours Automas, that take the place of a human player and mimic the effects that player has on you.”

To that end, Pedersen and his team want to make their Automas behave as human as possible, which requires identifying all mechanics in the game that allow players to interact with each other. It might mean blocking action spaces in a worker-placement game, or taking ownership of a location in an area-control game. From there, it’s a matter of designing the Automa so that it can perform these actions in a realistic way.

Ricky Royal, the designer responsible for the solo variants in games like Pax Pamir’s second edition, Birds of a Feather and Guilds of London, echoes Pedersen’s thoughts that understanding the element of human behavior is key to creating a believable solo opponent. The trick, though, is finding the balance between difficulty and approachability.

“The key phrase I keep in my mind is ‘playability’,” Royal says. “We often talk about creating an ‘intelligent’ opponent to play against when developing a solo variant. Developing this automaton is like working on a sliding scale, with simple and dumbed-down on one end, and complex and intelligent on the other. Somewhere in the middle is a Goldilocks zone where playability is king.”

When designing a solo experience from the ground up - that is, a board game intended to be played alone rather than as a variant on a multiplayer game - Royal says he aims to keep downtime to a minimum; forcing the player to fiddle too much with their non-existent opponent can kill a lot of enthusiasm.

“We want the soloist to spend most of their time making decisions and thinking about their own strategy,” he explains. “Players want to play.”

Pedersen’s approach is similar, and usually results in a purging of unnecessary mechanics.

Beyond making the Automa behave as a human would, Pedersen says that it’s also important to keep the AI as rules-lite as possible and function with minimal effort on the part of the player.

“Because of this, we cut away everything from the Automa that doesn’t directly impact the interactions,” he explains. “This, for example, often means that our Automas often don’t have player mats, because the state of those normally only has an indirect impact on the interactions.”

If you think in video game terms, Automa could be considered the programmed coding that handles all the processing and AI rules. In that medium, the player isn’t expected to govern the game itself, only the character they’re controlling. Pedersen aims to match that same level of agency in his games - which is to say that the player should be able to focus on their gameplay without having to expend unnecessary energy on managing the Automa.

The designer points to Viticulture as an example. The Automa in Jamey Stegmaier’s strategic game of wine-making doesn’t actually run a vineyard like players do. What this means is that, in most cases, the Automa is simply not playing the same game as the players. There is a fine line between automation and complexity, though, which can be difficult to walk.

“The more advanced we make the Automa the better we can keep the feel of the game, but the second principle dictates simplicity,” Pedersen admits. “The most important step in resolving the conflict is to allow the Automa not to play the same game as the human player. Instead it plays a much simpler one that intersects with the game the human plays [only] at the points of interaction.”

The result, Royal says, ought to be a positive impact on the player’s psyche - an impression that their actions during the game had a meaningful effect on the outcome.

“We want the game to respond to the game state, but not to do so with complex heuristics or flow charts; we want to keep it quick and simple,” he explains. “As we develop the game’s mechanisms for responding to player actions, we gravitate towards the ‘dumb’ end of the sliding scale to keep things quick and simple, but every now and then, one of those ‘dumb’ decisions hits and looks like a very clever response made with agency.”

These “hits,” as Royal describes them, can often dictate how fulfilled or hollow a game experience leaves us as players. It doesn’t take many hits to scratch a strategic itch, though, so designers need to be careful not to overuse them lest the soloist be left feeling like their decisions don’t matter at all.

“The key is finding those simple methods that give enough clever hits that we have a suitably challenging opponent in the game to play against,” Royal says.

So why make the effort to design these solo experiences in the first place? For Pedersen, the appeal should be obvious for those whose schedules make it tough to get a group of people together for game night.

“Not only is it much easier to get the game group together when the size of the group is one,” he laughs, “[but you also] don’t need to convince the others to play your favourite. Solo gaming is not merely ‘play a board game without other people’ - it’s a different take on board gaming that allows you to enjoy board games in a different yet familiar way.”

Pedersen says to imagine that you’re a cyclist, and that you enjoy road racing. But then one day you discover the existence of mountain biking, and your perception of what it means to enjoy biking has doubled. It’s an entirely new facet of a beloved hobby that you might have yet to experience.

“You might find that you want to do both, and get more fun from biking that way,” he says. “Or you might find that you enjoy riding a mountain bike alone in the forest more than participating in bike racing on paved roads. I think that the exact same thing goes for multiplayer and solo gaming.”

Indeed, that sense of discovery seems to be snowballing across the greater board gaming hobby. Last year, Pedersen presented some fascinating statistics in a BoardGameGeek forum that illustrate just how prominent solo tabletop gaming has become. His research says that nearly one quarter - roughly 24% - of board games in the online database are playable solo. This is an increase of 11% over 2008, a decade prior.

What this steady growth illustrates is just how popular solo board gaming has become. What once might have been considered a small, niche corner of the board game hobby is no longer so, and the number of options for single-player experiences has never been higher. In fact, Gloomhaven, the current number one ranked game on BoardGameGeek, is an incredibly popular go-to solo adventure. As solitaire modes such as Pedersen’s Automas become ever more commonplace and feel closer to their absent human counterparts, could it be playing board games alone will become just as accepted and popular as loading up the latest video game for some precious alone time?