“Desperation breeds innovation”: The board game publishers banding together against the shipping crisis

Small but mighty.

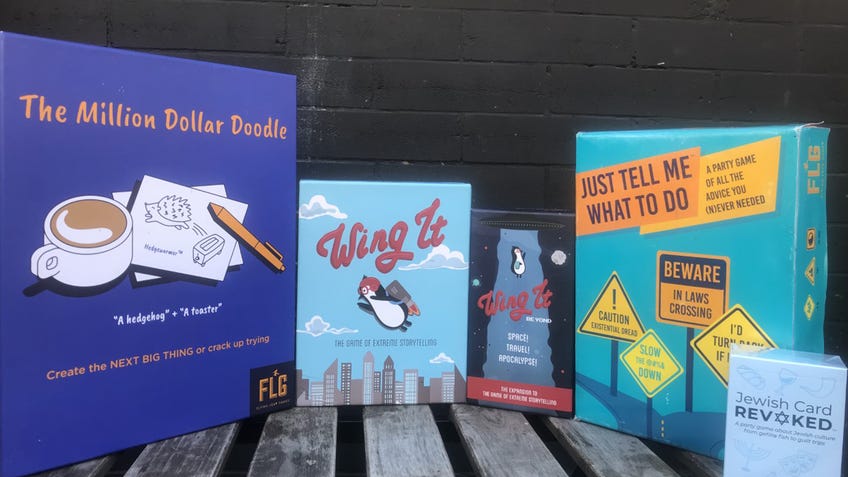

Earlier this autumn Molly Zeff, co-founder of board game publisher Flying Leap Games, was quoted in a Time article talking about how the recent shipping crisis had affected their business.

As a co-owner of Flying Leap, Zeff - who is also a member of GAMA, or the Game Manufacturer’s Association, as well as a co-founder for a national tabletop diversity fellowship - has suffered through over a year’s worth of issues relating to manufacturing and shipping delays, as well as increasing costs, caused by ripples from the continuing COVID-19 pandemic.

From reports of the price of shipping containers going from $5,000 to $20,000 seemingly overnight, to big-name publishers such as Fantasy Flight Games - the studio behind the Arkham Horror Files universe - putting up their prices to negate the rising costs, the industry and its customers have certainly felt the disruption caused by the pandemic.

After the release of the company’s most popular title, Wing It: The Game of Extreme Storytelling, in 2017, Flying Leap had found its party games in demand last year, despite the pandemic meaning that many people weren’t allowed to mix households. However, when ordering the units that Flying Leap needed to fulfill anticipated customer orders for the holidays in late August 2020, Zeff encountered some unexpected issues. By December 1st, Zeff was informed that the ship containing the studio’s units had arrived in Long Beach, where they would normally be transported to a warehouse before being shipped to customers. Due to a lack of available space at the port, Zeff’s games were still sitting on the ship over a week later yet to be unloaded.

“Imagine, you’re a tiny company and you’ve already been hit by the pandemic,” Zeff describes. “Then on top of that, your best-seller is just sitting on the water because there’s nowhere to dock.”

That had me extraordinarily scared because that means a single shipment of a game could put you out of business.

It took until December 31st for Zeff’s units to arrive at Flying Leap’s warehouse, but by that time the co-founder had already taken action to fulfill the company’s outstanding orders. By contacting various retailers across the US, Zeff successfully managed to shift enough units around to get the games to customers before the holidays arrived, comparing the entire experience to putting together “a jigsaw puzzle”.

The incident sent alarm bells ringing in Zeff’s head: “My income had taken a major hit, because we make party games and in four of the seven countries we ship to it was illegal to gather with people outside of your household.”

Come summer 2021 and Zeff discovered, in a single text from her co-founder, that the price of shipping containers had rocketed over the last year. “My co-founder told me that someone was now paying $20,000 for a container that usually costs $3,000,” says Zeff. “That had me extraordinarily scared because that means a single shipment of a game could put you out of business.”

I think we could get there with enough publishers who were producing more games.

The news caused Zeff to “plunge into action” and start looking into shipping companies and manufacturers across the world. After gathering a total of 90 different companies and contacting 30 of them, Zeff compiled a spreadsheet of varying prices for creating and transporting board games: “I wanted to try to find a place that wasn’t suffering too badly.”

Update: This article previously stated that Zeff had negotiated for farming organisations, which was inaccurate. This has since been updated to reflect the correct information.

Recalling her background in negotiation training, Zeff decided that the best course of action would be to form a collective of small board game publishers from the people she knew. Zeff reached out to friends who had also wanted to procure several hundreds of card games in time for the holidays, eventually gathering together 11 different studios - 75% of which were minority-owned. Once together, the publishers calculated exactly how many units they wanted and what they could collectively afford to pay, eventually landing on around 20,000 to 30,000 units in total.

We would have benefited from reaching out to a few more medium-sized publishers.

Despite shopping around at the various manufacturing and shipping companies Zeff had previously scoped out, the collective were unfortunately unable to secure a deal that worked for both them and the companies. The biggest issue was that most manufacturers and shipping companies wanted to create and transport more units than the collective needed, alongside the fact that the different publishers each had only one or two games that needed to be produced - which made the opportunity even less desirable.

“If we had been able to get up to 40,000 units, then I think that would have helped us a lot,” Zeff explains. “I think we could get there with enough publishers who were producing more games.”

The co-founder came to the realisation that with the support of a medium or larger-sized publisher, then the collective could have more of a chance to gain the traction it needs to secure a fairer deal. “We would have benefited from reaching out to a few more medium-sized publishers,” Zeff says. “Even having some of those names on the list could make a big difference.”

I don’t think we’re going to see the same kind of port shutdowns that we’ve seen in the past.

Despite the setbacks, Zeff confirms that the collective will continue to look into solutions to the current manufacturing and shipping situation, learning from their mistakes along the way: “I would say that it kicked me into action to find creative solutions and to look at places outside of China for manufacturing.”

In regards to the shipping crisis in general, Zeff takes a surprisingly optimistic approach. “I’m holding out hope that the shipping crisis is a result of the pandemic,” she says. “I don’t think we’re going to see the same kind of port shutdowns that we’ve seen in the past.”

The co-founder believes that once the shipping backlog is cleared and the demand for online shopping continues to fall, that companies will be able to rise up to meet studios’ and customers’ needs once again.

“My very hopeful optimistic side of myself wants to say people will shop local more, unfortunately, don't think that's going to happen.”