How an illegal card game launched Mario maker Nintendo

The history of Hanafuda.

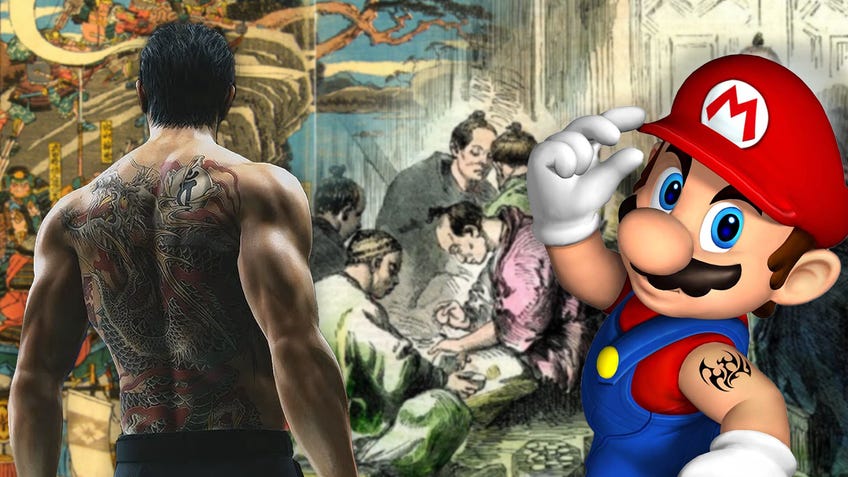

How did a simple deck of playing cards, printed with beautiful and elegant illustrations, lead to underground gambling, organised crime and the foundation of one of the world’s largest video game companies - Nintendo, the maker of Mario, Zelda and Pokémon? This is the history of Hanafuda.

It’s the 1500s and the insular island nation of Japan is in the midst of a bloody civil war. The Sengoku Jidai, or warring states period, was a time of near chaos for the serving classes of a feudal system on the brink of collapse as powerful Daimyo families sought to lay their claim on the throne.

Amongst all this chaos, in the year 1543 a Portuguese trading ship was blown off course, carrying some of the first Europeans to ever set foot on Japan’s shores to the island of Tanegashima, just south of Kyushu.

This was the start of what would end up being centuries of Western influence on the political makeup and technological advancement of Japan and its people. Alongside all sorts of genuinely life-changing inventions that Japanese citizens were being introduced to by the Portuguese traders - who were now setting up colonies and trading posts on Japan’s shores - there was a strange stack of illustrated cards.

These strange cards that the Portuguese traders played games with were an early variation of what we now know as the standard 52 playing card deck. The version that likely made its way into Japan would be more familiar to modern audiences as a tarot deck’s minor arcana. Four suits of swords, cups, coins and clubs would range in numerical value and would see knights, knaves and kings at the top of each suit. Around this time the deck only consisted of about 48 cards but would be used for similar games to the ones we play today, focusing on trick-taking and gambling.

As trade with Western nations became more prevalent and knowledge of the cards spread throughout Japan, it wasn’t long before decks were being made by Japanese people themselves. These first Japanese decks made during the Tensho period mimicked the makeup of the Portuguese decks that they were based on, albeit with a visual style and organisation that better fit the new Japanese audience, and are now commonly referred to as Tensho Karuta.

For quite a few decades these cards grew in popularity, becoming more and more of a household item for those that could afford to purchase them or make their own set, with regional games being created and the playing card deck entering Japan’s national lexicon. That was until the Edo period, and the Tokugawa Shogunate’s iron grip sought to eliminate Western interference from their now subjugated island nation.

It’s the 17th century and Japan is in a new state of unification, seeking to suppress social unrest in the once-wartorn country and now finally acting as one nation. Or at least it was supposed to be, anyway. After years and years of outside influence from Christian Europeans, Western culture and practices were starting to become normalised and accepted in those spots closest to foreign trading ports, with many Japanese nationals even converting to Christianity.

Meanwhile, the Tokugawa Shogunate become more and more oppressive in their reign with harsh penalties of beheading, death by boiling and even crucifixion seemingly being doled out for even the most minor of offences. The Shogunate were not big fans of Euro-Christian influence and the effect it was having on their sovereignty and culture. (Which, when looking at how other indigenous people have been treated as part of colonialism, I guess you could say is at least an understandable reaction.)

Karuta playing cards were officially outlawed in 1648, leading to the emergence of Hanafuda decks as we know them today.

With Christianity now seen as a threat, this led to a lot of punishment being thrown at those who had converted or converted others. After the Christian-led Shimabara Rebellion in 1638, Christianity was completely outlawed in the country. It wasn’t long before the third Tokugawa Shogun, Lemitsu, enacted the Sakoku Isolationist Policy. No-one could come into or out of Japan’s borders without express permission from the Shogunate. There were to be no more European trading posts - save for a single port on the island of Dejima where only the Dutch could import goods, and under strict surveillance. Japanese people would not be allowed to craft ocean-going vessels, foreign books were banned from import. The Shogunate refused to allow outsiders to influence the culture and politics of the nation.

With this fierce crackdown on Western imports came a crackdown on any objects associated with them - including those decks of Karuta playing cards, which were officially outlawed in 1648. It was here that the Hanafuda decks as we know them today would properly start to form.

By this point, gambling with playing cards was very popular amongst the citizens of Japan, to the extent that it was quite difficult to crack down on. Officers enforcing the law would look for certain card designs that they associated with those original Portuguese playing cards and confiscate them. In response, underground gamblers would produce cards with different designs to try and obfuscate what they were playing. This led to an almost slapstick level of back-and-forth as gamblers created new designs that would then become popular enough for law enforcers to recognise, which led to a new design becoming popular - and so on and so forth until eventually we come to these gorgeous and abstract designs that are still being printed today.

Unlike Western playing cards, the values of the suits are hidden amongst the designs of what, to the innocent eye, seem just like small illustrations. Almost like postcards. By learning those designs, though, you’ll see that the cards are split into 12 different suits matching the months of the year.

Gamblers created new designs that became popular enough for law enforcers to recognise, which led to new designs being made.

Each suit is represented by the flora and fauna associated with those months. This is where the modern name of Hanafuda originates, roughly translating to “Flower Cards”. Look at March and you’ll see the famous Japanese cherry blossoms blooming, while in August the autumnal Japanese maple leaves gently drift down the cards. Each of the four cards in a suit then have varying scores based on the contents of their illustrations, with simple flowers scoring one point, paper strips scoring five and so on.

Those scores and how the cards are used vary depending on the game you’re playing. If you’re playing Koi-Koi, one of the more popular Hanafuda games that has survived to this day and resembles a Western game of poker, even more sets can be made: all the red poetry tanzaku cards, all four of one suit, all single point cards and so on. The name Koi-Koi is a taunt used to signal that you want to double-or-nothing your winnings after finishing a set and taking a round. It’s basically the Japanese version of “Come and have a go if you think you’re hard enough”.

This versatility in the deck, and all the different games that it led to, are what made these cards so popular and also what prompted those using them in the shady back alleys and private games throughout the country to continue to adapt them and avoid detection with the intricate visuals on the cards. With private illicit games came gambling, and with gambling came money, which pretty much always leads to crime.

One of the popular gambling games that can be played with Japanese playing cards is Oicho-Kabu. Although designed for Kabufuda cards, you can play with Hanafuda by simply removing the last two months. Similar to baccarat, in Oicho-Kabu you draw three cards hoping to score as high as possible, but if you ever go over nine then your score will equal whatever the smallest number is in your total figure. For example, if you scored 15, you’d only actually score five. One of the worst hands you can draw is 8-9-3 - totalling 20, which is effectively scoring zero points. In Japanese, the numbers 8, 9, 3 are pronounced yattsu, ku, san - which can be condensed into ya-ku-za, meaning no-scorer, low-life and, eventually, gangster.

In Japanese, the numbers 8, 9, 3 are pronounced yattsu, ku, san - which can be condensed into ya-ku-za, meaning no-scorer, low-life and, eventually, gangster.

It’s not entirely clear where the organised crime syndicates of the Yakuza we now know of today originated, but in Edo period Japan there were two wings of criminality that are thought to have been some of the first instances of their operations. The Tekiya, who were essentially dodgy merchants peddling illicit, stolen or counterfeit goods, and the Bakuto, who were involved heavily in gambling.

The Bakuto would set up shop in towns and on highways - sometimes even in collusion with local governments as a way of syphoning labourers’ earnings back into their hands. It was also the Bakuto that originated the tradition of large elaborate tattoos on their members’ backs, often resembling the very Hanafuda cards they were playing with. The gamblers would play at the tables shirtless, almost as an advertisement to those in the know. To this day, tattoos are very looked down upon in Japan as they’re often associated with criminality - many Japanese bath houses across the country still ban those with tattoos from entry to this day.

The Bakuto, and subsequently the Yakuza, have long been associated with Kyushu Island, often regarded as the largest source of their members and its activities involved in the gangs’ origins. Kyushu also happens to be a stone’s throw from the original landing point of that first Portuguese trading ship.

Fast-forward to the year 1889. Craftsman Fusajiro Yamauchi founds a playing card manufacturing company in Kyoto, Japan. Gambling was banned in almost all forms from the year 1882 but, as is always the case when you make something illegal, still carried on outside of the state’s eyes.

The Yakuza are now heavily affiliated with all forms of gambling and playing cards. Despite the production and sale of Hanafuda cards being a perfectly legal act, a lot of retailers were worried about the connotations of selling things that were predominantly used by dangerous organised criminals.

Unswayed by the dangers to his public image, Yamauchi names his brand new playing card company Nintendo Karuta, with the express purpose of making and selling Hanafuda cards. The phrase Nintendo is often assumed to mean “Leave luck to heaven”, in keeping with the company’s gaming image, but an alternative translation can be read as “The temple of Free Hanafuda”. Within a few years, it becomes the largest manufacturer of Hanafuda cards in Japan.

The company saw its fair share of financial troubles over its turbulent first few decades in business due to wars, slow and expensive manufacturing processes, and a new playing card tax which halted the production of Western-style playing cards that they planned to introduce years earlier. But with continued and substantial effort the company continued to grow, eventually even pairing with Walt Disney to release card sets featuring Disney’s animated characters.

This led to the company focusing more on the children’s toy market, especially after the sale of Hanafuda cards began to go out of fashion as gambling ‘alternatives’ such as pachinko began to rise in popularity - an industry that still dominates Japan today.

With its original product falling in profitability and the once-lucrative deal with Disney falling out of favour with the purchasing public, the Nintendo Playing Card Company, as it was now known, pushed outside of its comfort zone and began to invest in businesses far from its usual wheelhouse including instant rice, a taxi service and even a chain of love hotels - which you can Google in your own time if you’re not familiar.

None of those business ventures really took off, with the taxi service being the only real beam of sunlight before it was quickly snuffed out by disputes with local drivers’ unions. With a business on the verge of collapse, Nintendo’s only real saving grace was its newfound speciality for manufacturing electronic devices, following the release of its first-ever electronic toy in the 1970s. A watershed moment for the company, this led the company to focus hard on what would soon become its video game production wing, leading to the gaming powerhouse that is modern-day Nintendo, creator of Super Mario, The Legend of Zelda, Pokémon, Animal Crossing and much more.

It’s almost baffling to think of the now super-clean, family-friendly, cartoon company that is Nintendo being a primary source for organised criminal gangs to buy their gambling cards from, but even today you can grab yourself a deck of Nintendo hanafuda cards - including sets with Mario and friends adorning the illustrations. As well as a beautiful set of cards, you’ll be holding a fascinating piece of history in your hands.