Indie RPGs are telling some of the greatest mystery stories on - and off - the tabletop

Hercule Poiroll.

In his introduction to The Best Detective Stories of 1928-29, author Ronald Knox famously presented his “Ten Commandments” of writing good detective fiction, including guidelines about how many secret passages should appear in a story (one), and advice on how to best make use of twin brothers (they must be “duly prepared for”). Later, S.S. Van Dine (a pseudonym for art critic and mystery writer W. H. Wright) exhorted that romantic plot lines had no place in detective fiction, decrying the distracting nature of the desire to “bring a lovelorn couple to the hymeneal altar”.

Early 20th-century writers of detective fiction were very particular about what could and could not constitute their stories. While it’s easy to scoff at such attempts as mere traditionalist gatekeeping, it’s important to recognise that these writers were very literally concerned with the game balance of such stories. Mystery novels were, in a very real sense, considered as games. In his introduction, Knox explained that, “the detective story is a game between two players, the author of the one part, and the reader of the other part”. Van Dine cared that his readers “have equal opportunity with the detective for solving the mystery”. The preoccupation was over how “fair” a mystery story was and whether or not the average person felt that a mystery was, in fact, solvable.

Mysteries are popular in modern roleplaying games. For instance, Candlekeep Mysteries, an anthology of mystery adventures for Dungeons & Dragons, was a bestseller in 2021 and garnered widespread critical acclaim. And while roleplaying games could simply perpetuate the genre’s tropes, modern tabletop RPGs - especially small-press and indie titles - leverage what Janet Murray calls in her seminal book Hamlet on the Holodeck the “expressive” quality of the TTRPG medium (as opposed to a mere “additive” quality) in order to reconstruct, and even deconstruct, the whodunit genre. In other words, such games aren’t just mystery stories translated into game form; they wield the particular affordances of the medium of tabletop roleplaying - shared storytelling, social dynamics, choices unbounded by computational constraints, at-the-table calibration - to deliver unique experiences.

RPGs aren’t just mystery stories translated into game form; they wield the particular affordances of the medium of tabletop roleplaying to deliver unique experiences.

While many traditional tabletop RPGs are about whether or not players can discover the various clues to a mystery’s solution (“Players can roll dice to attempt an Intelligence (Investigation) check of Difficulty 15 to spot the bloodstain, but only if you look under the carpet”), the GUMSHOE family of games centres the process of solving rather than the searching. In Night’s Black Agents - a modern-day vampire-espionage GUMSHOE game - designer Kenneth Hite writes, “In espionage novels and films, the emphasis isn’t on finding the information in the first place. Usually, the heroes are awash in facts and intel, trying to piece them together to deduce the opposition’s plans, or to plan a counterstrike of their own.” If a clue is present in a scene and characters have the necessary in-game abilities to find it, they automatically do so - no dice roll needed. Furthermore, Hite instructs GMs to “ensure that any clue [...] is available not only to players using the ability specified in the scenario, but to any player who provides a credible and entertaining alternate method of acquiring that clue”. Night’s Black Agents’ subordination of clue discovery in favour of clue interpretation makes for a unique mystery-solving experience that makes players feel especially competent.

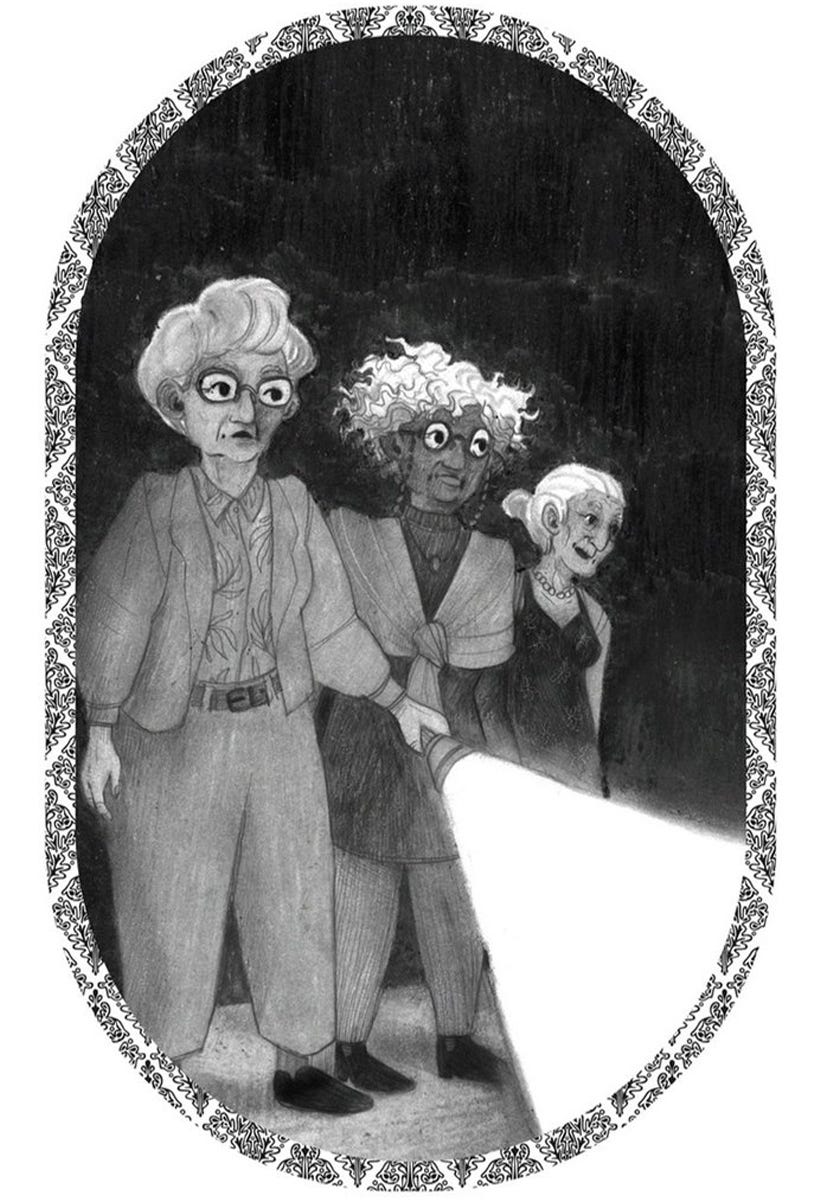

Brindlewood Bay, Jason Cordova’s game of amateur-sleuth grandmas, brings this act of clue-interpretation even further into the spotlight. (Disclaimer: The author has contributed to a Brindlewood Bay supplement.) In a game design twist that would surprise fans of mystery movies and books, neither the author of an adventure nor the GM knows a mystery’s solution at the onset. Instead, players are given various opportunities to make discoveries from a table of random clues, and then must collectively invent a solution based on those clues - a solution which then becomes enshrined in the story’s canon. As such, players fit the solution to the experience they’re having, the mood they’re in, and the characters they’re drawn to. The experience of solving the mystery is less puzzle-solving, and more creative worldbuilding. The rules even allow for retroactive changes to scenes and characters on the players’ part. “What’s the best way to explain why we discovered a broken heel at the scene of the crime?” a player might ask. “What if Lady Braitwaithe has been walking with a limp this entire time and that detail just struck us?”

The players' unusual vantage point gives them a view of the narrative that few other media can match.

If Brindlewood Bay asks players to devise their own solution, Black Armada Games’ Lovecraftesque demands that players do so competitively. In this game of cosmic, unknowable horror (essays on the problematic nature of HP Lovecraft’s original writing included), the narrator is tasked with introducing one clue in each scene. At the end of a scene, players all “leap to conclusions” and secretly note down what they think the solution to the mystery is given the current slate of clues. However since the role of the narrator rotates every scene, the new narrator is incentivised to introduce a new clue that conforms to their vision of the mystery, forcing everyone else to change their theories. Over the course of the game, theories mutate as though in a convoluted session of the children’s folk-game Telephone, contaminated with each player’s desire to control the thread of the narrative. Retracing everyone’s trail of theories is part of the game’s fun, a wholly unique way to experience mysteries.

Then, there are games where the crime-solving is secondary, explicitly used as set dressing for drama. In their game Magic School Mystery, Tanner Wilson explicitly writes, “This isn’t a mystery-solving game; at no point will anyone playing a Student Character ever use real-life deduction. The point of the game isn’t for players to solve a mystery but to tell one.” Magic School Mystery does not promise a neat, deducible crime to solve. The GM is encouraged to create mysterious events on the fly; even the main game mechanic for mystery-solving, the asking of specific questions following such a mysterious event, is designed to be improvisational. “There doesn’t have to be a fair and logical trail leading back from your clues to the rest of the mystery,” Wilson emphasises, “because it’s not a puzzle to be solved”. Magic School Mystery’s promise is to deliver the atmosphere, mayhem and misadventures of a pre-teen magic school novel - a strange, magical mystery just happens to be the perfect framing device for such a story.

Games, particularly indie tabletop roleplaying games, occupy the unique position of allowing us to simultaneously experience stories from several different angles. Author, consumer, participant, critic - these roles all coalesce into the singular figure of the “player”. The players' unusual vantage point gives them a view of the narrative that few other media can match. Mystery stories comprise just one genre - any and all genres of storytelling can be re-examined, recreated and even revolutionised through the affordances of a game.