Green Players: The tabletop studios and designers incorporating sustainability into board games

How publishers are adopting eco-friendly practices to help the planet.

A huge part of board gaming as a hobby is, undeniably, the excitement of opening a big box and seeing all the exciting stuff that lies within. For many, collecting games and miniatures is a hobby in and of itself, whilst the tactile side of playing tabletop games is all the more significant in an increasingly digital age.

However, some within the hobby are concerned about the sustainability of board games. Plastic is commonly used as a cheap, durable material that can be highly detailed, but it’s bad for the environment. It’s not as simple as using materials like wood and paper instead, as these can be sourced in various different ways, some more eco-friendly than others. Even transporting board games takes its toll on the environment.

Manufacturing and designing for sustainability comes with drawbacks, impacting cost and durability. However, as the value of the board game market increases both globally and on crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, some are trying to navigate this landscape, both to create greener games and to inspire others to do the same.

Iain Chantler created the website Sustainability in Games to fill in what he felt was a knowledge gap in the tabletop industry. The site, due to fully launch in March, aims to provide free resources for designing and manufacturing sustainable games. Chantler, a Design and Innovation graduate from the Open University, also offers a consultancy service for industry figures and consumers.

Even if it’s only 20% of people who want more sustainable board games, having the option to buy those would make the industry better.

For his final year project, Chantler analysed the ten highest-funded board games on Kickstarter, and found that many contained components such as tokens, meeples and miniatures, paper money and poker chips that, while aesthetically unique, were functionally identical. His proposal was to use high-quality generic components instead.

“While board games are not the least sustainable hobby - these are things that people keep for a very long time and then generally resell, so the environmental impact of board games is not nearly as bad as it might seem - this is literally waste, because it’s duplicated material that people don’t need," Chantler says.

Dr John Gallagher, assistant professor in Environmental Systems Modelling at Trinity College Dublin, agrees, saying that the long lifespan of tabletop games is not a “get-out clause for the board game community”.

“Every sector has to take its own responsibility for being sustainable,” Dr Gallagher says.

However, Chantler acknowledges that the tactile and visual side of board gaming is “half the hobby”, saying that he’s “absolutely guilty” of buying games with interesting figures in the past.

We have to find a balance between reducing plastic, but also not increase cardboard usage to compensate.

“Board games are so unique in that they’re just such nice, intricate objects to purchase and have sitting in your house,” he says.

Instead, Chantler wants people just to do what they can.

“I don’t think the entire industry will shift, and I don’t think it needs to shift. These big-box Kickstarter games can still probably exist; even if it’s only 20% of people who want more sustainable board games, then them having the option to buy those would make the industry better,” he says.

Last summer, game manufacturer HABA USA incorporated pull-tab stickers to seal its boxes, along with paper bags and bands to manage game components, in order to reduce the plastic usage in its packaging. Many HABA products use wooden components, the materials for which are sourced sustainably, and the company has DIN ISO 14001 certification, signifying its “environmental management system meets international industry specific environmental standards”.

“HABA’s general approach is that children are our future, and if we’re not leaving them a healthy and safe planet, that defeats the purpose of us saying they’re our future,” HABA USA games manager T. Caires writes over email.

HABA doesn't ship its games in case pack boxes, which are designed to fit specific amounts of specific games. “Instead, we ship in loose pallets or grouped cartons what the retailer orders, to reduce unnecessary cardboard,” Caires says. However, this means that the games aren’t as secure and, combined with the original pull tabs being “too easy to pull”, some games were coming open during shipping.

We’re hoping as more companies shift toward this sort of packaging it will be perceived less as a fluke and more of a good thing.

“We have to find a balance between reducing plastic by using these tabs, but also not increase cardboard usage to compensate,” Caires says.

Three of the 60 games produced by HABA USA last year were packaged without shrink wrap as a test. However, some consumers perceive products lacking shrink wrap as ‘used’ and less desirable, whilst “online retailers like Amazon require us to shrink-wrap these products when they’re shipped to their fulfillment centres”.

“We’re hoping as more companies shift toward this sort of packaging, though, it will be perceived less as a fluke and more of a good thing,” Caires adds.

When designing products for sustainability, “somebody has to sacrifice something” - such as component quality or money - according to Dr Gallagher. This applies to consumers as well: the demand for sustainable products needs to be vocalised before its need can be met.

“That’s an end-user shift; that’s not top-down, that’s bottom-up - gamers themselves asking and pushing for sustainability.”

Although Caires acknowledges this issue, they say that “if you make the decision to do that from the beginning and calculate that into the cost from the start, you can make it work”.

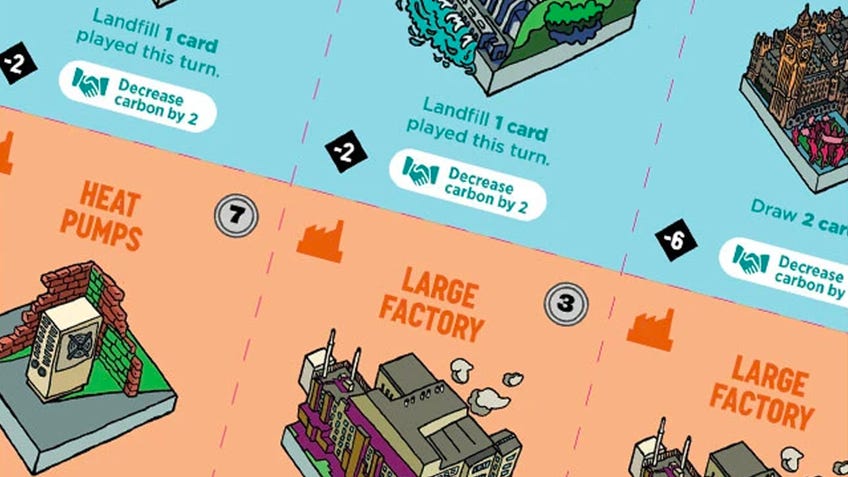

Carbon City Zero also runs with the idea of sustainable manufacturing. The deckbuilder, produced for the climate charity Possible, challenges players to design a carbon-neutral city. It was co-designed by Dr Paul Wake, reader in the Department of English at Manchester Metropolitan University, and Dr Sam Illingworth, associate professor in Academic Practice at Edinburgh Napier University.

The game is available as a free print-and-play, similar to the pair’s environmentally-themed custom Catan expansion Global Warming, but physical versions funded via Kickstarter were designed to be “fully reusable, replayable, and recyclable”.

Eliciting disagreement about the potential power of the cards (and what they represent) in a real-world setting is exactly what we hoped to achieve.

They eliminated plastic entirely, asking players to source their own tokens for the game and avoiding shrink wrap. Boxes were kept “as small as possible” to reduce the environmental impact of shipping. They also sourced a UK-based printer, the Forest Stewardship Council-certified company Ivory Graphics, as they didn’t have to ship the bulk of their product internationally. However, these measures came with some drawbacks.

“While we likely saved some money by avoiding tokens, printing and shipping was perhaps a little more expensive,” Illingworth and Wake say in a joint statement.

The designers also feel that these sustainability measures would likely have a negative impact if the game was taken to retail: “A larger box would give it more presence on the shelf, and most customers would likely expect to see it protected in shrink wrap.”

They didn’t aim for one-to-one simulations of real-world environmental models for these games - although extensive research was carried out for both Catan: Global Warming and Carbon City Zero. Rather, they hoped to start conversations.

“For example, some people might think that the Hydropower card [in Carbon City Zero] is overpowered, whereas others might think that the Biogas Plant card is not powerful enough. From a game mechanics point of view we tried to avoid creating any cards that were obviously ‘broken’ but eliciting disagreement about the potential power of the cards (and what they represent) in a real-world setting is exactly what we hoped to achieve,” they say.

Endangered, a cooperative animal conservation game released last year, similarly hopes to inspire players. Players are activists trying to keep endangered animals alive in the face of human environmental impacts including poaching, oil spills and deforestation.

“I wanted something that players could engage in, something that they could feel an emotional connection to. The environment has always been a passion of mine, so really it was an obvious marriage,” designer Joe Hopkins says.

It can be overwhelming just having a conversation about conservation.

Consequently, Hopkins researched each scenario separately, coming up with unique mating and migration mechanics for different animals. The Center for Biological Diversity, the partner for the game’s Kickstarter campaign, provided feedback during development. Hopkins’ primary concern was creating a fun game, wanting to represent real-world issues without being strictly educational, although he hopes the game can get players talking and thinking about conservation.

“It can be overwhelming just having a conversation about conservation, [it] can feel like: ‘I’m just one person, I can’t save every species’,” Hopkins says. “There are small steps that everyone can take, and that’s really what I want people to [take away]: there’s always hope, there’s always something you can do to improve the situation.”

Focusing on sustainability presented some issues. Endangered was primarily manufactured using wooden and cardboard components. Hopkins “agonised” over the decision to ship the game in shrink wrap, but was unable to find a suitable alternative. The game’s theme also proved to be a double-edged sword for a brand new IP; although its initial Kickstarter run was successful, raising around $42,000, it fell shy of two of its advertised stretch goals. By contrast, its New Species expansion recently raised almost $144,000 on Kickstarter, hitting every stretch goal.

“Trying to put out a game about conservation, it definitely can be difficult to convince people: ‘This is actually worth playing, it’s not just going to make you feel bad, or feel like you’re part of the problem’,” Hopkins says.

James Wallis, veteran designer and studio manager of The Green Board Game Company, also grapples with the issue of branding and sustainability. The publisher, part of the Asmodee Group that includes labels such as Fantasy Flight Games and Catan Studio, produces the BrainBox series of trivia games. These small boxes declare themselves “70% recycled and recyclable” but ship with a plastic sand timer and die out of necessity, due to their durability and being an enjoyable and tactile part of the experience.

Nobody buys a game thinking ‘I’m gonna throw it away’, but people need to be aware that in the long term it is going to be thrown away or recycled.

On the one hand, Wallis feels that companies should take pride in sustainable manufacturing; the company plans to add recyclable symbols to BrainBox as part of an upcoming redesign. However, it “will not be splashing that our games are sustainably produced”, as customers could pigeonhole it as an environmental company and be put off - an issue exacerbated by having “Green” in its name.

“The company, in the past, has done some [environmentally-themed games] - we don’t any more, for the reason that they don’t really sell,” Wallis says.

Despite all the logistical challenges that come with designing for sustainability, some publishers are adamant that it is an important topic that should be discussed more widely.

Blue Orange Games, which minimises plastic usage by focusing on natural and recycled materials, has partnered with environmental projects such as Save the Bay and PUR Projet, and released environmentally-themed games including Planet and Photosynthesis.

Chantler encourages people to design for sustainability from the outset, focusing on how to reduce a game’s component complexity and make it “less materially demanding”. For example, choosing a stylised art style that could be printed at a lower resolution, using good-quality plastic to reduce waste or utilising recycled plastic for low-detail components. He hopes to produce a graded seal of approval that companies can apply to have printed on their games.

Although certification could help encourage publishers to manufacture more sustainably, Dr Gallagher feels that obtaining them could be a challenge for smaller companies.

“The big challenges of any small company, no matter what product it is, is: ‘I want to be sustainable, there’s this approach I can take [to] get a stamp or a certification, but I have to do a lot of work to calculate my footprint or I have to provide information and it has to be approved and I have to pay for that,’” he says.

There is no question that we are facing an environmental calamity, everybody has to change what they’re doing.

Chantler acknowledges these restraints, but says that incorporating some aspects of sustainability can be commercially viable. He calls for better recycling information to be included in modern board games - he describes trying to recycle some games as a “minefield”.

“Nobody buys a game thinking ‘I’m gonna throw it away’, but people need to be aware that in the long term it is going to be thrown away or recycled,” Wallis agrees. “That material is not going to be a game for the whole of its life, it’s going to become something else - and the question is whether it becomes another useful object, or detritus in a landfill, or [ends up] floating in the sea.”

Caires encourages companies to focus on sustainable material sourcing, to reduce their use of mixed materials, to make games more recyclable and to research factories’ sustainability standards.

“There’s a lot of waste in the board game industry, in how the games are produced and sold, as well as what consumers do with them when they’re ‘done’,” they say. “[Sustainability is] something that I’m excited to champion for in the industry.”

Maybe manufacturing board games sustainably is only a drop in the ocean, but the ocean is made out of all of those drops

“Don’t just assume that the way it’s always been done is the way it should be done now. The world is changing; there is no question that we are facing an environmental calamity, everybody has to change what they’re doing,” Wallis adds.

“Everyone can help, everyone can do a little bit. Yes, maybe manufacturing board games sustainably is only a drop in the ocean, but the ocean is made out of all of those drops,” Hopkins says. “It’s just like any conversation for change that needs to happen: it shouldn’t be a conversation that’s isolated to one specific spot.”